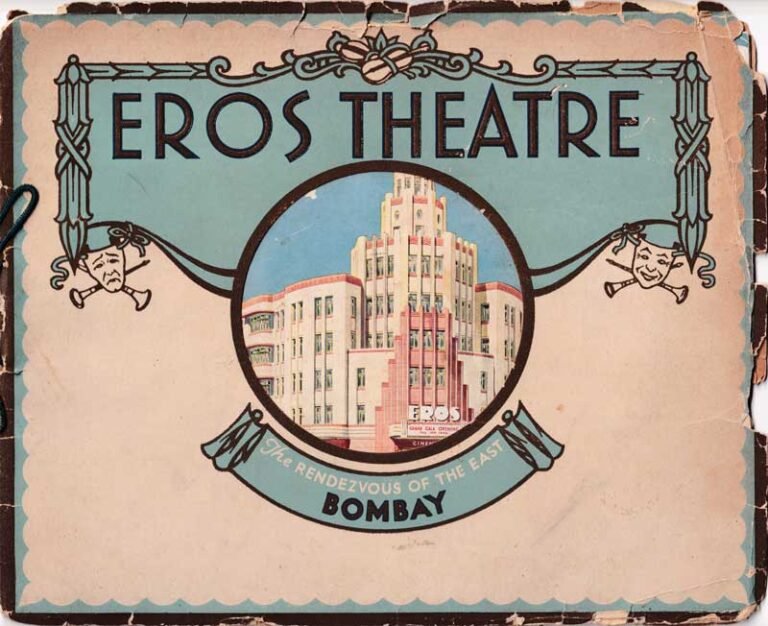

For anyone who has stepped out of the busy Churchgate Terminus in south Mumbai’s Oval precinct, the towering sight of the iconic Eros theatre, just across the road, unmistakably dominates the landscape. Described as “Bombay’s* most modern place of entertainment” at the time of its inauguration in 1938, the Eros building surges forth into the city’s skyline like a dazzling ocean liner pulling into the dock.[1] As a corner facade building, bookending a row of modern Art Deco apartments built in the 1930s, along the Western end of Oval Maidan, the theatre acted as the “pivot” of what was then the new town emerging on the Back Bay Reclamation site. [2] Named after the Greek god of love and desire, the theatre became not only tangible proof of Bombay’s burgeoning modernity, but also drew from Classical imagery. Its visible confluence and contrast with the Victorian Gothic structures around it spelt a shift from earlier styles into a modern century, while also laying out a roadmap for their co-existence. More importantly, like its namesake, the Eros building came to stand in for desire – for modern comforts, aesthetics and ways of being. While several professionals and experts from around the world were involved in the construction of this incredible picture palace, it was one businessman’s vision to give the city of Bombay a “standard of entertainment” unlike any other.[3] To call Eros just a cinema, therefore, would be an injustice.

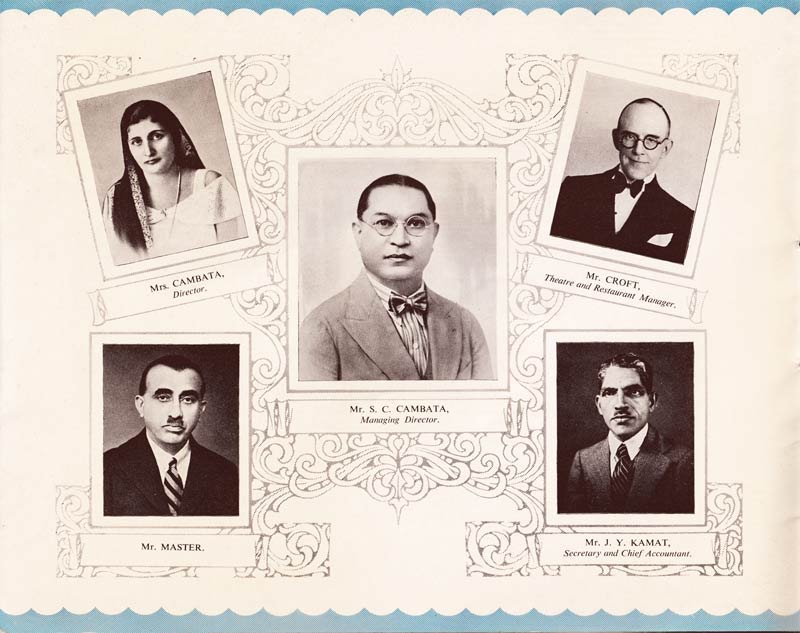

Born in 1883, Shiavax Cawasji Cambata (or S C Cambata) had been at the forefront of shaping Bombay’s culture long before he commissioned the Eros theatre building. Originally a resident of suburban Versova, Cambata contested in the Bombay Municipal Corporation by-elections in 1933, winning his seat with an impressive majority. “Hindus, Mohammadans, Parsis and Christians have voted solidly for Mr Cambata, which was an evidence of his wide popularity among men of all communities,” waxed eloquent an entry in the hefty volume of His Imperial Majesty King George V and the Indian Empire. [4]

Cambata was included in the volume among many prominent personalities in India under the British Raj, and with the company he kept, it was befitting that he was a cosmopolitan, well-traveled man. It was from his many voyages around the world that the seed of Eros theatre germinated. Cambata is said to have drawn inspiration from the statue of Eros he saw at London’s Piccadilly Circus, in the theatre district.[5] [6]

As a review of the theatre’s opening, published in The Bombay Chronicle, descriptively put it, he was looking to construct a picture palace that would be “the pride not only of Bombay or India but the whole of the East [sic].” [7]

‘The Epitome in Design, Style and Finish’

Commissioned in 1935 and inaugurated three years later, in terms of visuals, Eros was the most distinct out of these picture palaces. “The presence of the Art Deco style reached its peak” with Eros, write authors Sharada Dwivedi and Rahul Mehrotra, in their comprehensive book on the subject, Bombay Deco. [10]Architect Sohrabji Bhedwar designed the building such that it had a distinct V-shape, with two wings on either side meeting at the wide entrance of the theatre. It was the “epitome in design, style and finish at the time,” Dwivedi and Mehrotra add.

As much as this building was about exhibiting moving images in its interiors, its exterior also had a grand, almost cinematic quality. The streamlining on the building’s curved facade gives the impression of a magnificent ocean liner, a symbol of voyages and cosmopolitan travels in the modern age.

Despite its wide, horizontal base, the Eros Theatre looks towering, transforming the city’s skyline. The light cream facade of the building is accentuated with red sandstone from Agra. The same shade of red is also used on ornamental details throughout the building, lifting its appearance up and making the structure look taller than it is. The ziggurat or the stepped tower that arches into the sky announced the emergence of this majestic new structure in the district, instantly becoming a landmark in the newly reclaimed neighbourhood.

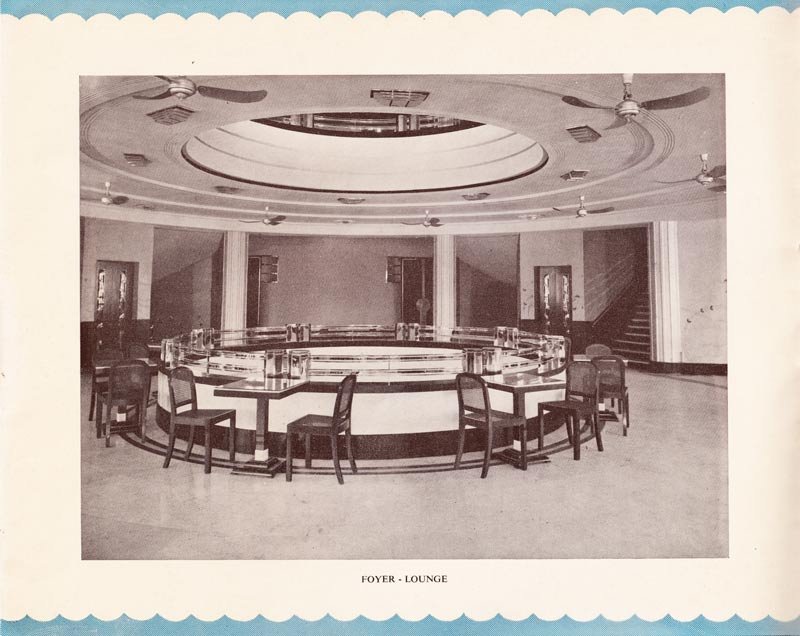

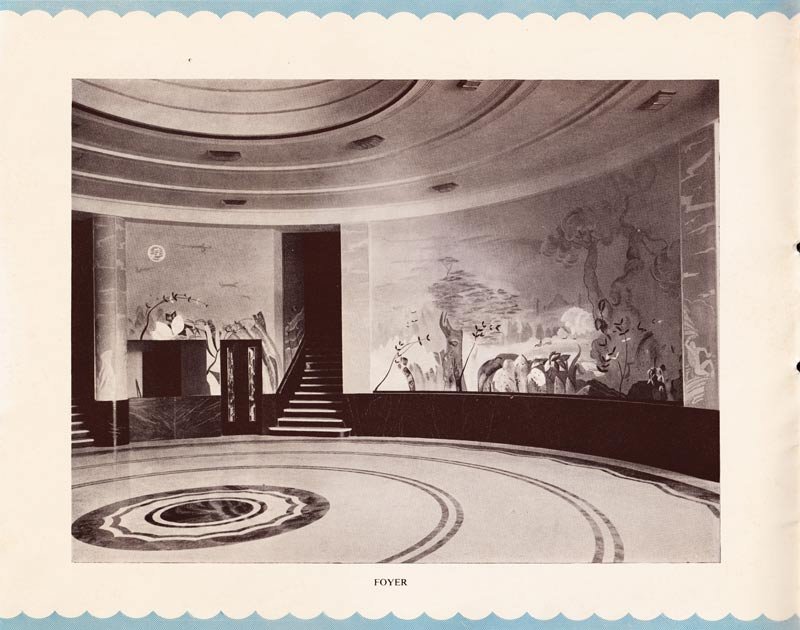

The plush interiors of the theatre also screamed modern luxury. Upon entering the building, one would find themselves in a foyer bedecked with white and black marble floors, accented with streaks of gold. The walls had painted murals depicting scenes from various parts of India, including a silhouette of the Taj Mahal, and various temples from southern India. Hexagonal lifts on either side of the foyer took patrons up to the boxes and balcony upstairs, where they would also find lounges, a soda fountain and a milk bar. “The soda water fountain was the meeting place during the interval,” says a 70-year-old patron of Eros cinema, and a long-time resident of the Oval precinct.

“Before the main movie there would be a cartoon that the kids were excited about. Then during the interval, we would naturally go for popcorn and chicken mayonnaise roll, mayonnaise jaasti,” he reminisces. ‘Jaasti’ is the highly adaptable Mumbai slang meaning “extra”.

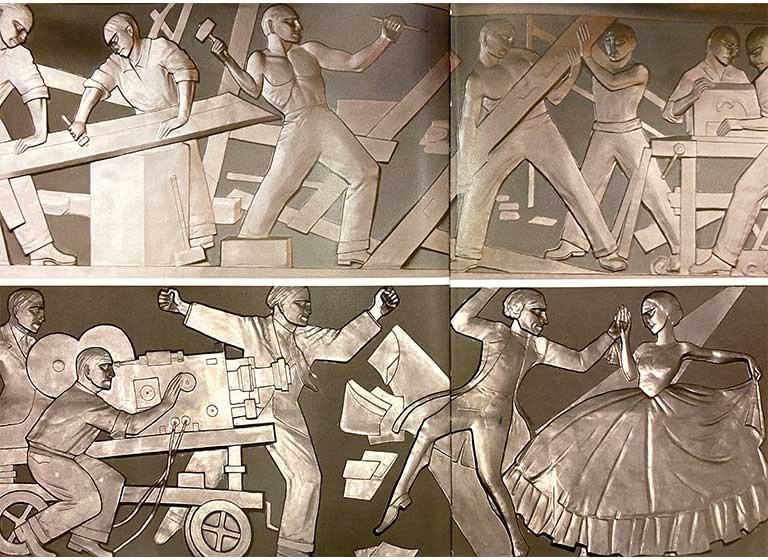

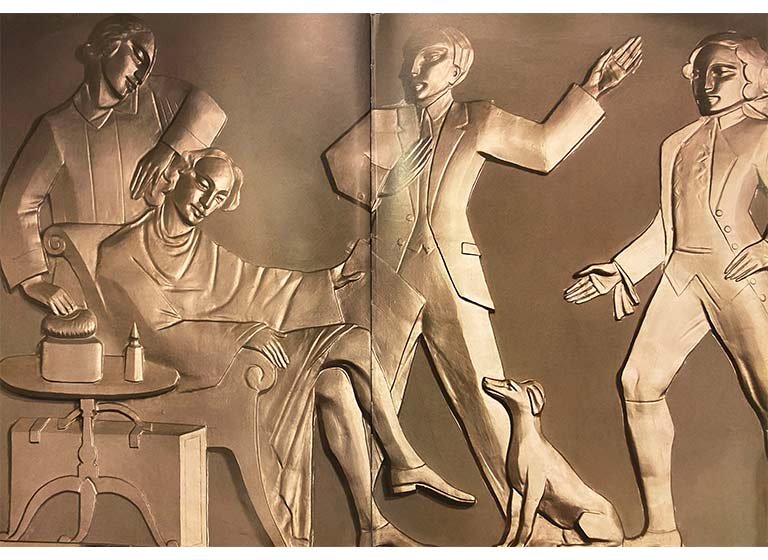

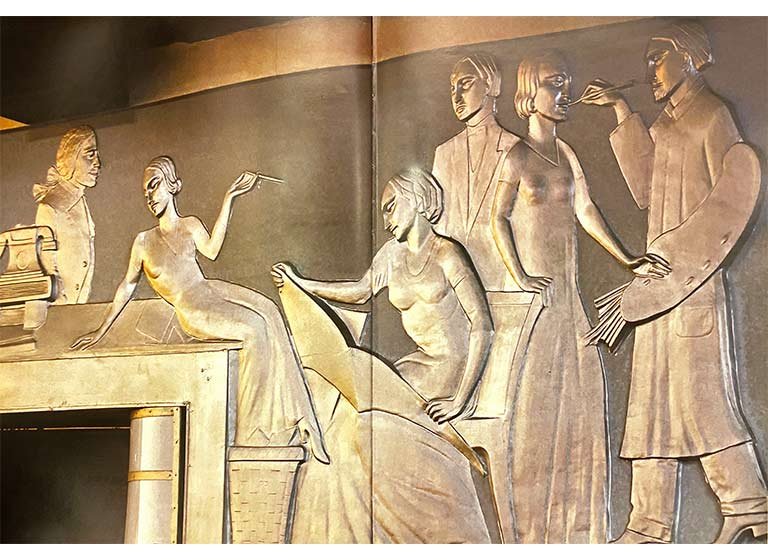

Inside the theatre, there were intricately sculpted bas-relief panels running along the walls, depicting various stages of film production. With a striking colour palette of silver and blue, the panels lent themselves to an incredibly illustrative form of storytelling. There were images of a set being constructed, actors getting hair and makeup done, and a director rolling the camera on a scene that is in action. While the building itself was meant to exhibit motion pictures, it also incorporated itself into the visual symbolism of this modern mass medium. In some ways, the audiences too, enveloped on three sides by these scenes from a film set, complete the narrative that the bas-relief sets out to tell. If the decorative relief panels on the walls are of what goes on behind the camera, the audiences form the collective in front of the screen, where the labour of film making is finally exhibited. One can, therefore, see Eros Theatre’s attempt to be more than just a concrete establishment, but a live, interactive and evocative structure that understandably became the talk of the town.

The inaugural brochure goes to lengths to describe the care taken by Cambata to ensure the establishment was at par with similarly chic offerings in the world. Though the Oval precinct resident was born only in 1951, he recalls hearing stories about the founder personally standing at the doors of the theatre in the early years, ensuring the patrons entering the building were well turned out.

The chairs in the theatre were also designed after the businessman “personally minutely examined chairs of all types in various countries of Europe and America [sic]”.[12] Cushioned with a “non-heating fabric”, the 1204 seats in the theatre were designed to withstand Bombay’s subtropical climate.[13]

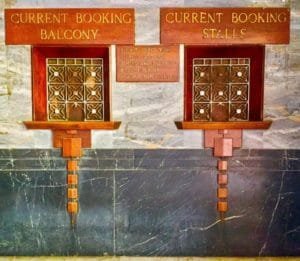

The concealed hat holders underneath the seats took into account the popular sartorial styles of the day (also an indication that the patron demographic included Europeans, and Indians who took to western attire). All the seats in the theatre were identical, regardless of the cost of the ticket. There were extra seats on either side of the last row, however, that were often occupied by couples looking for a semblance of privacy, the Oval resident recalls, playfully referring to them as Eros’ “coochie-coo couples”.

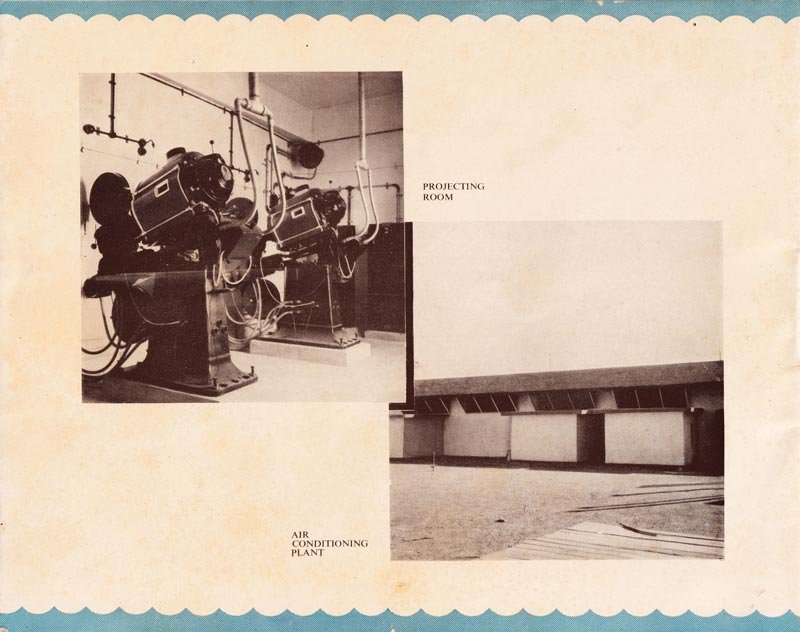

Most importantly, air-conditioning lent a respite from the heat of the city. By the late 1930s, several commercial structures and office buildings in Bombay were being equipped with air-conditioning units, and Eros was one of them. [14] Referred to as “Multitherm Units” in the brochure, the equipment was manufactured by the American firm Clarage Fan Company, in Kalamazoo, Michigan. As opposed to earlier systems in the city, the brochure asserted that the ones installed at Eros were different as they drew fresh air through powerful fans on the roof, as opposed to the basement. Five units in total were installed to cool the whole theatre, from the boxes, to the area under the balcony and the rest of the hall, making the air in the theatre “hygienically perfect” for the “health and comfort of its patrons”. [15]

Open-Air Restaurant, A Ladies Band, and More

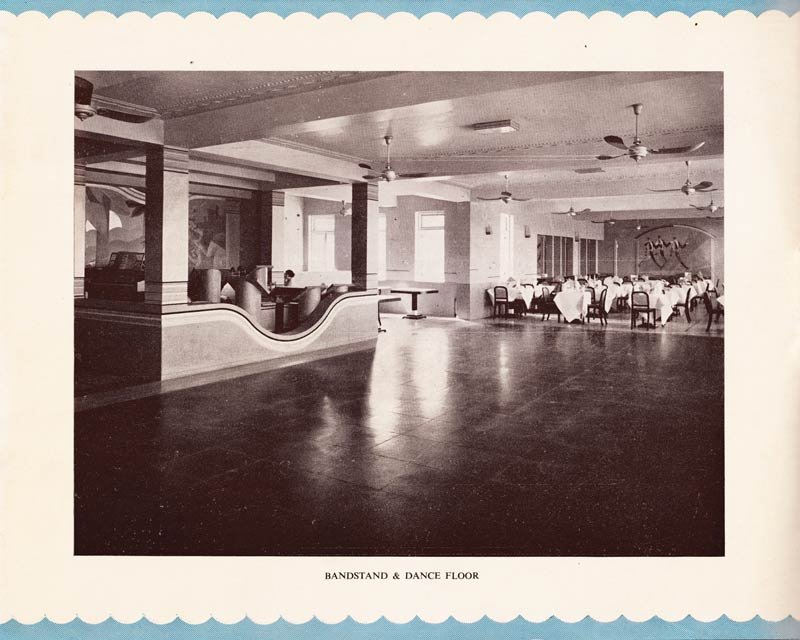

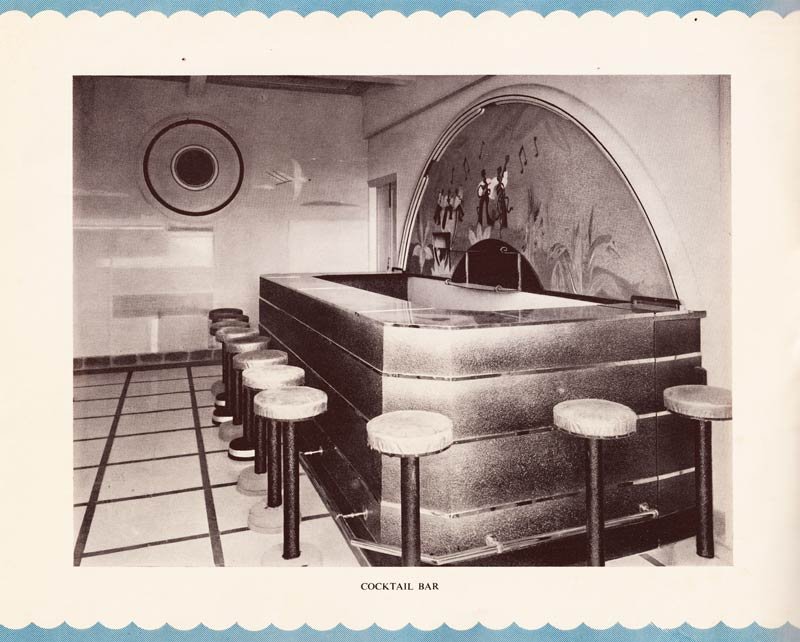

Notably, Eros, and several other Art Deco picture palaces of the time, were constructed as mixed-use commercial centres, with space for shops, offices, and even residential apartments. One cannot speak of the vision of Eros Theatre without also mentioning the other exciting recreational opportunities it offered the city of Bombay. “The Eros can proudly boast of being the first theatre in the East in which is included a first class restaurant [sic],”. Located on the first floor of the building, on the Western end, the restaurant had a spectacular view of the entire Back Bay area, and could accommodate upwards of 500 guests. Large glass panel doors installed along the length of the restaurant could be opened up to usher in the cool sea breeze, converting the establishment into an open-air restaurant when required. The spacious dance floor in the centre of the restaurant, with a cushioned spring construction for ease of movement, was ideal for hosting many a soirée and nights out on the town. One of the biggest attractions of the restaurant, however, was the musical act – Ida Santerelli and Her Ladies of Spain. This was a broadcasting band, from England, composed entirely of women! The splendid collective of women, familiar on radio networks from Croydon in England to Kingston, Jamaica, promised “a regular feast of ideal music seldom to be had in India”. [16]

As much as Eros was a modern establishment for the cinema, it is useful to draw connections between these modern Art Deco picture palaces and what is widely regarded as one of the antecedents to cinema and cinema-going in south Asia – the Parsi theatre.

Cambata himself was a Parsi, and it is unsurprising that many of these Art Deco theatres were commissioned by eminent Parsi families. The continuum between the community’s patronage of, first, the stage arts, then cinema, is one that emerges more evidently in these modern Art Deco picture palaces.

Emerging in the mid-19th century, the Parsi theatre was an event for audiences to gather, enjoy discourse, discuss ideas, and inhabit spaces of cultural exchange.[18] Similarly, Bombay’s new picture palaces, complete with not only cinema exhibitions, but also restaurants, cabarets, musical performances, as well as stage theatre, were drawing people into the public sphere to interact with ideas, and with each other. The key shift, however, as Michael Windover writes, is that the glamorous construction of these new Art Deco theatres, “emphasized the modernity of the new everyday activity of cinema-going by framing it as modern and cosmopolitan”. [19] This was an activity and aspect of public culture that drew special attention to identifying itself as distinctly modern, through the modern visuals offered by the Art Deco styles.

A Site of Rendezvous

Eros’ location, as a veritable landmark in the new neighbourhood, also had a lot to do with its status as a centre of activity. When Cambata was deliberating the idea of Eros, the Back Bay Reclamation Site was still relatively vacant. By the time the building was inaugurated in 1938, the area was rapidly developing into “Bombay’s finest residential and commercial locality.” [20] Until the beginning of the 20th century, the land on which Eros now stands had a railway line extending from Chowpatty to Colaba. Belonging to the Bombay, Baroda and Central India Railways (BB&CI), the line was laid after the Back Bay Reclamation Company folded up in the 1860s, and the Government of Bombay reclaimed this strip of land. In 1930, when the reclamation of the Churchgate blocks on the Back Bay was completed, the Railway Company was directed to hand over the area between Churchgate station and the Colaba station. Once the railway line was dismantled, the vacant plot was delineated as a building area. A Times of India report from 1938 describes the plot next to Churchgate Station, where Eros now stands, as “the largest and most valuable”. [21] “This was acquired by Mr S C Cambata, and it became known later that the intention of the lessee was to erect a building which would be worthy of this fine site,” the report stated. [22]

Gopa Khandwala, age 58, who went to school in the Churchgate area, remembers spending a lot of her teenage years frequenting Sundance Café on the ground floor of the Eros building, which stood there for decades before shutting shop around 2010. “It was close enough to our school, it was inexpensive enough, so we used to hang out there,” she says, recalling the “sandwiches, burgers and Western, snacky items” on their menu. Down the road were her other frequent haunts, the iconic Gaylord restaurant, and K Rustom’s for ice cream. The Churchgate street, now known as the Veer Nariman Road, has for long been a site of liveliness and activity in the city.

The Oval Maidan next to the building was also a large, open space that lent itself to leisure and recreation at no cost. People from all walks of life could converge at the Eros junction, perhaps on their way out from Oval Maidan, or commuting from the suburbs through the arterial Churchgate station. The Flora Fountain tram junction, as the inaugural brochure also states, was only a two minute’s walk away. Even if one so much as glanced at the Eros building while passing it, they would be looking at a structure that Cambata had hoped would announce the ushering in of a new era of prosperity in the city. As Khandwala says, “it gives you some sort of innate joy, just to see something beautiful”.

The Eros Theatre, therefore, was an excellent way for people to participate in the unique modern ways of life being shaped in urban centres like Bombay. In a city that saw (and continues to see) economic migration from all over the country, the act of visiting a modern picture palace could form new ideas of community, separate from one’s regional or cultural dispositions.

More Than Just the Pictures

Cambata built Eros Theatre without any motives for “competition or profiteering”, but as “a contribution to the cultural development of this city [Bombay].” [24]

Several generations of his family thereafter have taken up the care of the building, and by extension the cultural cause that Cambata felt so strongly about. They were more than simply landlords of the building in which the cinema rented space, but were invested in India’s development as a film production centre at par with other industries in the world. His son, Rustom S Cambata, who would have been a 14-year-old teenager when Eros opened its doors in 1938, went on to meet Hollywood star Elizabeth Taylor, and hosted director Alfred Hitchcock in his Bombay home. [25]

But more importantly, while the building is a part of the family’s legacy, it also became a part of the community, weaving itself into people’s memories and lives. As the Oval resident recalls, the ballroom on the first floor of the building (that now houses a gymnasium) was where his sister’s navjote ceremony took place. The long-standing pharmacy on the side of the building was once an Agfa showroom where he purchased his first camera in 1964, for Rs 30. When the significance of Eros Theatre is read against the emerging public culture in Bombay in the early 20th century, the inaugural brochure’s title, ‘Rendezvous of the East’, becomes even more evocative. Indeed, Eros Theatre is a site of “rendezvous” or a meeting point for several things. For teenagers across generations to unwind and get a taste of early adulthood with friends, and also for passersby to look at this historic structure and admire it, at no cost. As much as the Art Deco style signalled an idea of internationalism, the walls inside the theatre had murals (which have now faded) of Mughal mausoleums and south Indian temples.

This modern picture palace with a Grecian name became a site of “entertainment” as Cambata had envisioned, but it also stood for a lot more. As Windover writes about the city’s Art Deco cinemas, “there was more to going to the cinema than simply watching the pictures”. [26]

* Bombay was officially renamed Mumbai in 1995. Wherever the article describes events before 1995, the city is referred to by its former name.

Suhasini Krishnan for Art Deco Mumbai

Suhasini is a writer and journalist based in New Delhi, with an academic background in Film Studies and History. Her research interests lie in cinema, modernity, and the making of an urban city.

Click here to view “Liberty Cinema: The Showplace of the Nation”, a short film by Art Deco Mumbai Trust.