Bombay in the 1930s saw a major transformation in its physical form and social structure. These reforms were reflected by the new, emerging trends in building design that represented a “modern” way of living. Inspired by international design trends, modern forms opposed the ornate, carved features of both Victorian furnishings and Indian styles, thus developing a cosmopolitan expression in an era of rising anti-colonial sentiment. Bombay as a thriving port city, gave roots to these global influences and was soon dotted with examples of new constructions in the modern style. The growing attention prompted newspapers, design journals and popular magazines to dedicate a regular section to new architectural and design ideas, surrounded by advertisements for home furnishings goods. Manufacturers and retailers built model showrooms to display new furniture designs in material form.

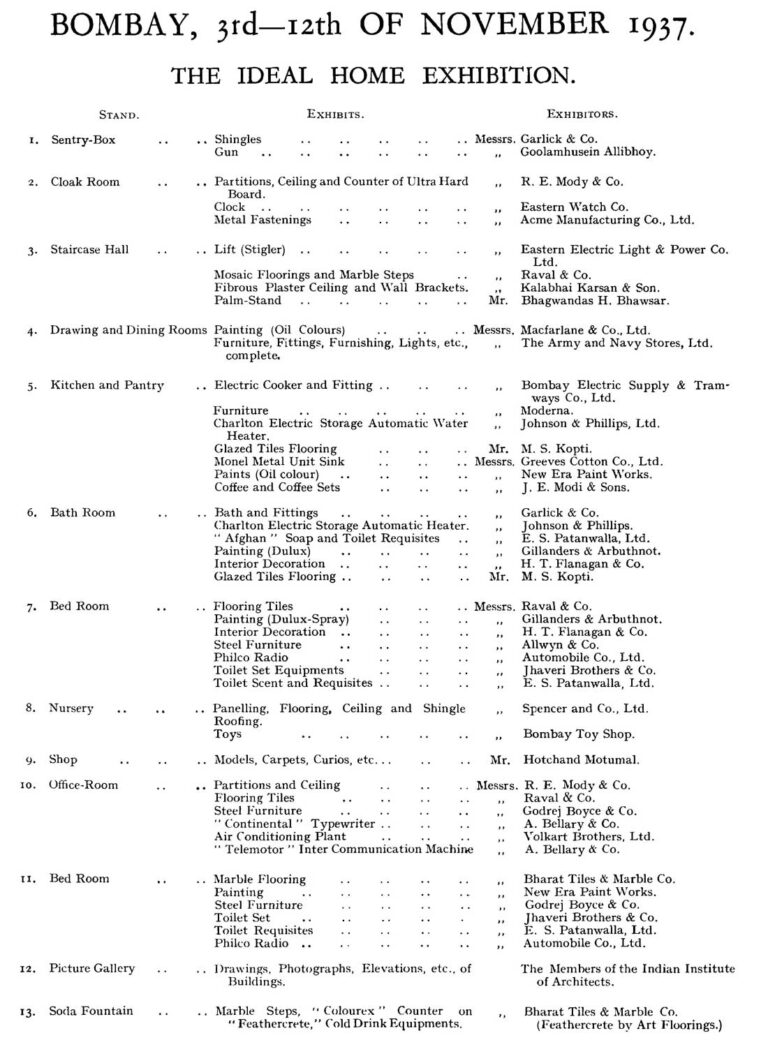

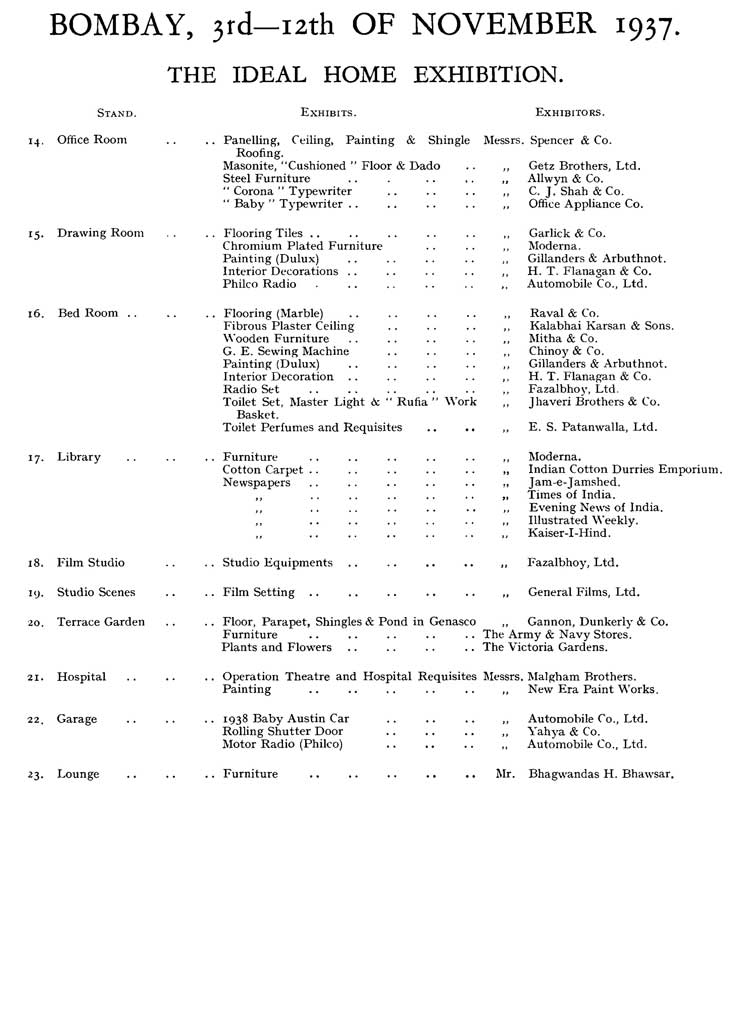

It was during this period of innovation that the Ideal Home Exhibition of 1937, organised by the Indian Institute of Architects (IIA), spotlighted a new outlook on modernism through domestic spaces by creating a public spectacle and drawing a new level of scrutiny and critique in the process.[1]

Emerging Urban Landscape of Bombay

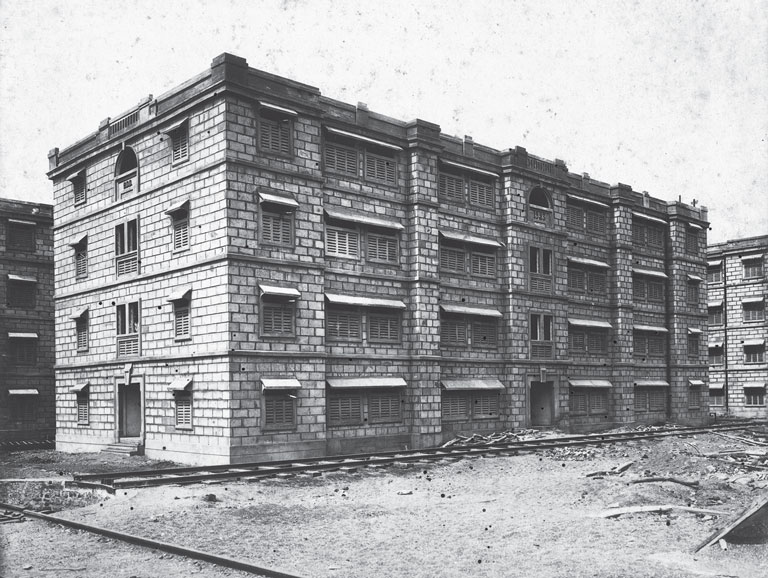

Up until the end of the 19th century, Bombay’s urbanscape was segregated into two distinct settings: the palatial bungalows and commercial establishments built by the affluent Indian merchants and industrialists in the “European town”, and the residential colonies of the labour class in the “native town”. With the rapid industrialisation and influx of new migrant workers, the spatial divide further worsened in the 1880s. Workers were forced to live closer to work where land was premium, and accommodated their families in single rooms. The growing demand for workers’ housing was initially met by private entrepreneurs who put up sprawling residential blocks known as “chawls”.

These consisted of two or three storey structures with single-room habitations and common toilet blocks and washing areas. Each tenement was occupied by five to ten persons, many a time crammed with multiple households due to the scarcity of working-class housing.[2] By the 1910s, 80% of the city’s population lived in chawls.[3] The jam-packed chawl became a symbol of Bombay’s working-class space.[4] The unsanitary living conditions of impoverished labourers in such congested, poorly ventilated chawls and slums became the breeding grounds for the Plague Epidemic in 1896.

In the years following the Great Depression, after a slump in the land market, building activities intensified. In the early 1930s, the city saw both a relentless expansion towards the northern suburbs and the much anticipated Back Bay Reclamation Scheme accelerated towards completion. These opportunities for construction, along with the availability of a new material – Reinforced Cement Concrete (R.C.C.) – that dramatically modified building techniques, sped up construction time and reduced construction costs, led to a building boom in the city. It was around the same time that a new generation of Indian architects emerged who were eager to adapt their western design sensibilities to the Indian context. The emerging style of Art Deco suited these conditions and took roots in Bombay. The characteristic geometric forms and streamlined facades combined with stylised features and motifs were perceived as “modern”.

While this modern architecture refused to use the ornamentation related to the traditional architectural styles, it also introduced a new concept of housing – apartment living. Instead of having rooms that served multiple household functions depending on the time of the day, the house was now segregated into various domestic spaces, each with a designated function. The configuration of each dwelling unit consisted of a living room which served as a social space, a special room with a dining table, a dedicated kitchen in proximity to these spaces and a bedroom for sleeping. Moreover, these apartment dwellings promoted the idea of “self-contained flats” i.e. the provisions of an attached toilet and bath within each household.[5] With the prices of land equating to the cost to build a house, it made economic sense for this typology of housing to develop as a social identity for a new emerging class of citizens – the middle class.

Rise of Modern Architecture

Residential buildings in this new style arose throughout the city: apartment buildings in the Back Bay Reclamation Scheme, luxurious flats and bungalows overlooking the sea on Malabar Hill, and ownership flats in the suburbs to the north. Modern material and equipment including lifts, concealed wiring, cladding of marble, flooring in terrazzo and glazed tiles, teakwood doors and windows with chromium fixtures, and steel grilles were widely used. These modern structures also employed other amenities such as electricity, artificial lighting, gas supply, water heating, drainage etc., which revolutionised modern living.

It is very difficult to define “Modern Architecture” because it claims no characteristics of its own beyond being simple and in harmony with modern ways of thinking and modern ideas of hygiene. [6]

– R. S. Deshpande, Modern Ideal Homes for India (1939)

The influence of modernism did not limit itself to apartment structures but extended to the interior living spaces with furnishings and decorations. Chairs, tables, beds, etc. designed with simple, clean lines, which were stronger, comfortable and more efficient – harbouring little or no dust on the smooth surfaces – came into common use. The furnishing was determined by its utility and fitness of purpose, which is the basis of all sound design.[7]

In 1939, Poona-based engineer and architectural writer R. S. Deshpande, in a series of his books on Modern homes, explained how such modern design is most suited for Indian conditions.

“In the first place, it is in keeping with our philosophical ideal, viz., ‘plain living and high thinking.’ Secondly, in a land of sunshine, with the contrasting effect of light and shadow, clear-cut features with smooth, sweeping curves present a more effective appearance. Thirdly, plain, smooth surface (whether in the exterior or interior of the house, on walls or furniture, which is one of the characteristics of modern architecture) allows much less chance for dust to deposit itself and is easy to clean in a tropical country like ours; and, lastly, it is the architecture of the masses, because with the growing development of indigenous cement industry, cement promises to be even cheaper, and the other material, viz., the aggregate, especially sand and gravel required for concrete, can be had merely for the collecting in the countryside. Thus, modern architecture caters equally for the needs of the rich as well as the poor.” [8]

While modern styles of furnishings were epitomised in Bombay’s wealthiest homes, they spread into wider use in the cosmopolitan city among the emerging middle classes, who were embracing the new consumer markets and building developments of the post-Depression era. From producers, traders, builders and new emerging professionals such as architects and engineers, new ideas about domestic spaces and decor offered Indians a creative appropriation of global modernity: cosmopolitan, metropolitan, thoroughly modern, and yet still Indian.[9] Modern living was now a symbol of change for the citizens of a new, emerging nation in an era of rising anti-colonial sentiment.

Reviewing this shift to the style moderne, which he termed as “naval architecture for stationery structures”, Kanaiyalal H. Vakil, noted journalist and art critic of the time, called on the Indian Institute of Architects (IIA) to educate the public in matters of architecture. In his address to the Council in 1935, K. H. Vakil requested the Institute to arrange periodic exhibitions on even a modest scale, explaining, “It is not enough to educate the architect. It is necessary to inform and educate the public as well. Let the public understand how architecture ministering to the manifold, massive, collective, complex requirements of modern urban and rural life must be accepted as a social necessity of the age.”[10]

The Ideal Home Exhibition of 1937

Taking note of the growing civic consciousness towards building activities and the increasing interest of the public in modern styles for Indian homes, the newly elected President of the IIA, Mr. P. P. Kapadia, took initiative to arrange for such an Architectural and Building Trade exhibition. After a year of planning, the Council finally opened the exhibition in 1937 at the Town Hall (now known as ‘Asiatic Society of Mumbai’) in Bombay.

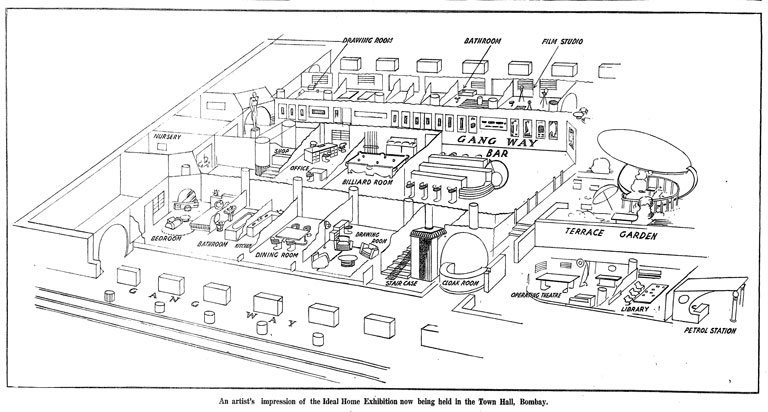

This was the first attempt towards such an exhibition in India and the entirety of the event was definitely new. In addition to architectural drawings, models and photographs of buildings recently erected, the exhibition would showcase fully furnished model rooms equipped with all the latest devices to meet the requirements of a modern home.[11] Each room was envisioned as a novel assemblage of various products from local firms and manufacturers – ranging from finishings for walls, ceilings, doors and windows, flooring, to furniture of all kinds, wall fixtures and accessories. This approach that spoke of an engagement with interior spaces as complete experiences, not as isolated objects or elements, was novel in many aspects.[12]

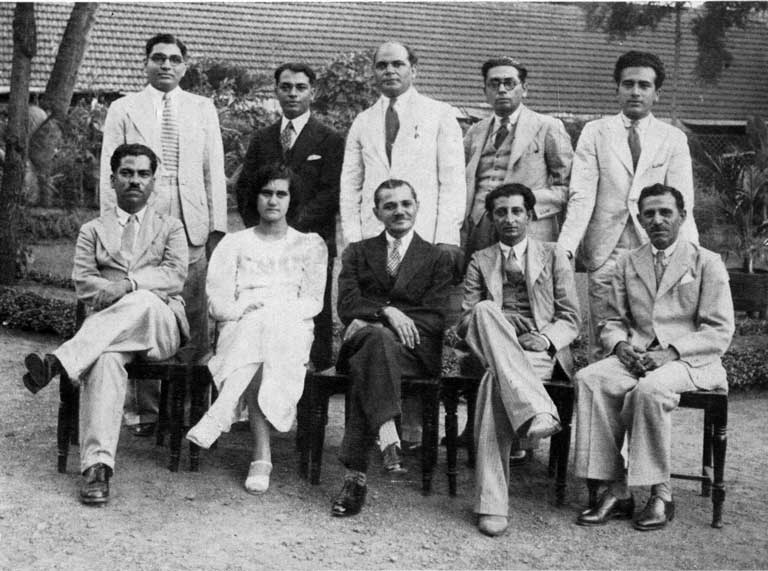

A special Entertainment Committee comprising the younger members of the profession, including the first woman architect of India, Perin J. Mistri, under the leadership of Mr. Yahya C. Merchant, Hon. Secretary, was responsible for the organisation and design of the exhibition. The layout of each room “ideal as they ought to be”[13] was thus designed and detailed by the architects on the Committee ensuring that the exhibits don’t emphasise the advertising value of the goods, but propose good design practices that would interest both – the architect and the layman. The Exhibition was inaugurated by Bombay’s Premier, Mr. B. G. Kher, on 3rd November 1937 in the presence of a large gathering at the Town Hall, Bombay. Declaring it open, he expressed his opinion on the exhibition – first of its kind, not only in Bombay but the whole of India – explaining that the word “home” has such happy association in the mind of everyone that any attempt to provide an ideal home was bound to receive encouragement, especially at a time when the housing conditions in Bombay were gaining the special attention of the Government of Bombay.

Mr. P. P. Kapadia, President of IIA, in his introductory speech at the opening ceremony argued, “That there is a necessity for such an exhibition there can be no two opinions, it concerns a sphere of life which touches every one of us vitally, a sphere in which we spend more than half of our lives.”[14]

“The exhibition, therefore, seeks to bring within the ken of each one of us, in a pleasant and easily accessible form, the latest devices to make this vital environment of our lives more comfortable, more modern, more congenial and perhaps more artistic”

– P. P. Kapadia, President, Indian Institute of Architects (JIIA, 1937)

The Ideal Home Exhibition, he claimed, would be a great asset for nation building as the building industry in the country has proved to be the most powerful factor in its economic stability and development. “For no industry as a whole deals in products of so many other industries and raw materials, employs such a vast number of skilled and unskilled men, finds such a natural outlet for technical men and artisans of the best sort to leave their mark permanently on the development of the country, as that of Building.”

Along with a boost to the industry, Kapadia hoped that the Exhibition would also make architecture as a profession more accessible to the ordinary man. Architects, who were viewed as ‘men who draw and paint fantastically beautiful pictures of houses, as they may like them to be built for rich clients and not for the use of ordinary man’[15], would be able to demonstrate their expertise that extended to every aspect of the design of homes and not only the external appearance.

Modern Furnishings

The exhibition was planned around a definitive circulation path for the visitors that would take them through each exhibit and picture gallery. Each room was a joint product of the “latest devices” from manufacturers including wall materials, ceilings, carpets, rugs, pavings, furniture of all kinds, electrical fixtures, artificial lighting, sanitary fittings and other modern appliances. These model rooms were then not limited to domestic spaces such as the bedroom, kitchen, library but also included an operation theatre, petrol station, film studio and bar, thus promoting an improvement in the quality of life through modern health facilities and through a very particular vision of urban sociability.

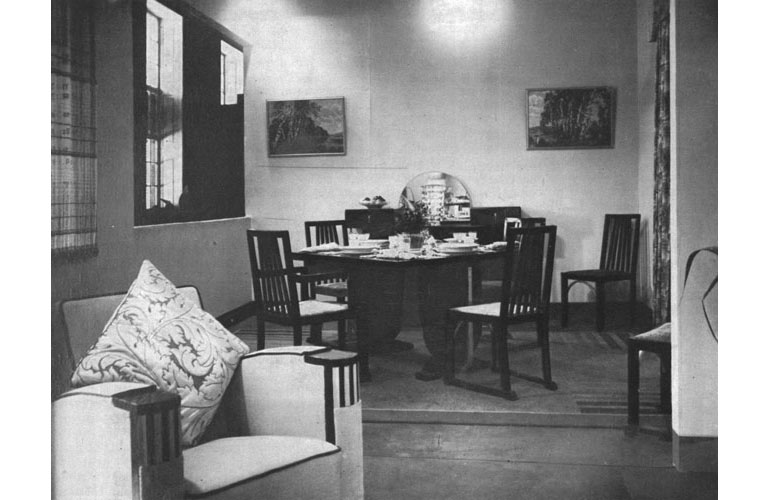

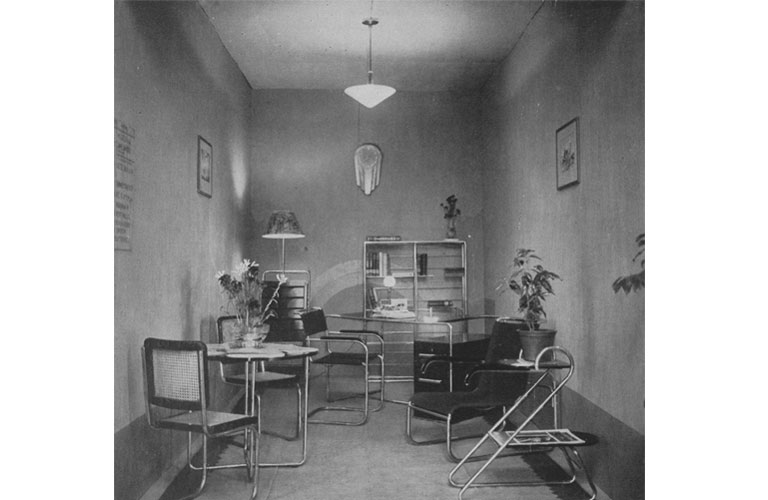

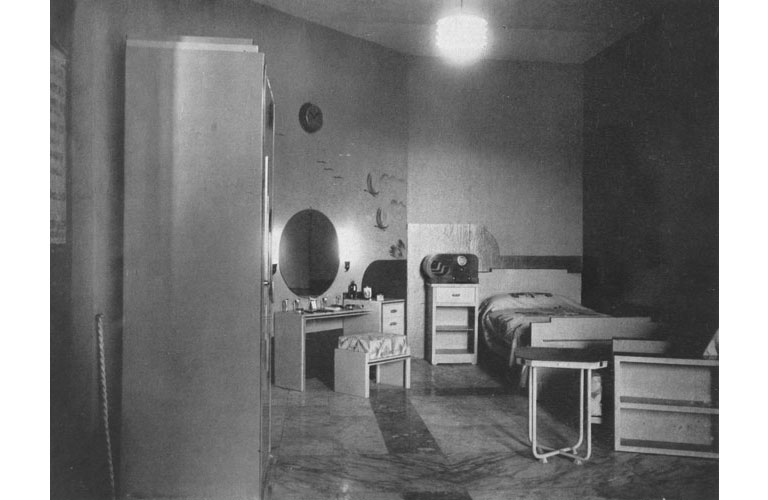

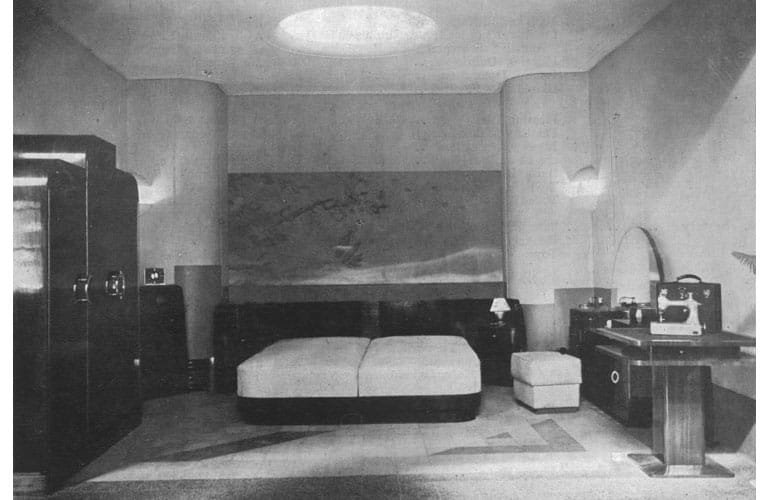

Modern built-in furniture in simple yet stylistic forms, with clean cut lines and bold shapes, stood in stark contrast to the traditional furnishings. Arm chairs, wardrobes and beds were made in wood and finished with veneers to include metal accent details. The chrome plated tubular furniture showcased in the drawing room, library, office room and also the bedroom, traced Bauhaus influences with its simple and light design.[16] The suitability of these materials to the tropical climate of India, compared to the solid woods used in traditional furniture, made it more appealing as a “modern” alternative.

An advertisement, by one of the exhibitors of such steel furniture, Allwyn & Co., read: “Best, because it is unaffected by heat or humidity – cannot warp or crack. Burglar proof – protects your jewels and papers. Fireproof – saves its contents intact”.[17]

In keeping with the latest technologies, the design of model spaces also included modern appliances and devices. The radio in the drawing room, sewing machine in the bedroom and the typewriter in the office, rendered the home “modern” and up-to-date. The Radio or radiogram, for this instance, was now advertised as a social necessity:

“Entertaining people is extraordinarily simple if you have a good radiogram. In fact, round this marvellous instrument can be built all kinds of afternoon and evening parties. If you have half a dozen friends for dinner the radio will supply the background music to the cocktails, while during desert it will give you the day’s news”

– “Modern Instruments Make Entertainment Easy” (Times of India, 3 Nov, 1937, p. 22)

The “all-electric” kitchen and pantry, finished in flooring tiles and oil paints, displayed modern appliances including the electrical cooker, electric water heater and also the steel sink which promoted the ideals of health and hygiene in the space. [18] With the development of electricity, modern plumbing and drainage, the exhibit was a perfect model for the intelligent use of such equipment, which has now become a necessity for modern living.

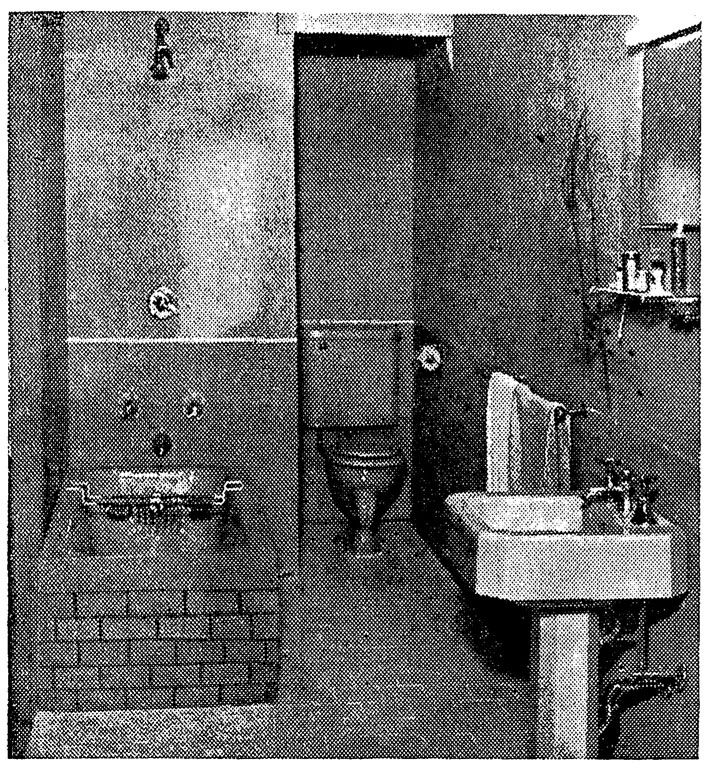

Modernity with “beauty” was defined in bathrooms by bathtubs, washbasins and other fittings. The 11 ft by 5 ft modern bathroom exhibited by Garlick & Co. showcased chromium plated fittings, shower, towel-rails, toothbrush rack and tumbler holder.[19] Vitreous tiles available in various colours to match the sanitaryware were used for cladding and dado. These were not entirely unique as manufacturers including the Bombay Electric Supply and Tramways Company (BEST) and the sanitary fittings firm Richardson and Cruddas also had model showrooms.

In addition to these rooms, there were also exhibits for a modern operation theatre, a garage with rolling shutters, a terrace roof garden showcasing water proof paving materials and, what can best be termed as a ‘Film studio’, with sets displaying ancient and modern backdrops placed side by side.

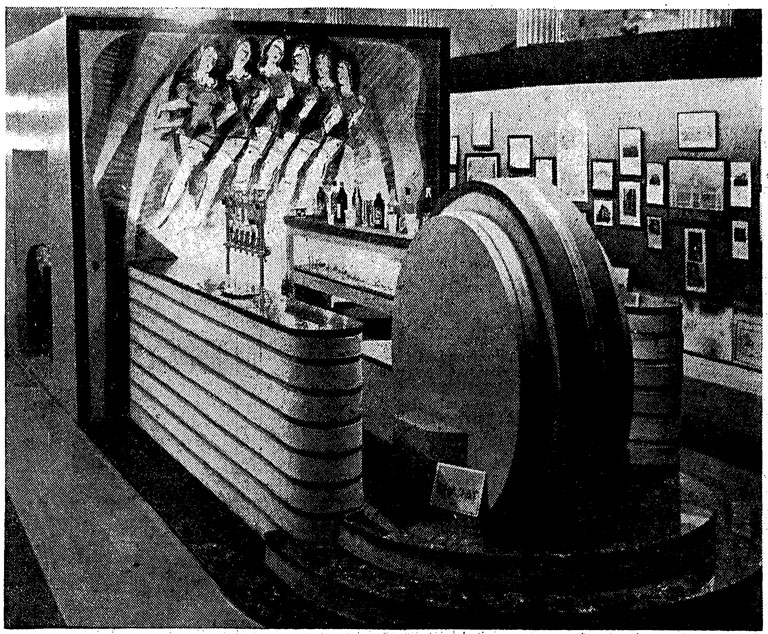

The centrepiece of the exhibition, however, was the design of the ‘Ultra-modern bar’ by Bharat Tiles and Marble Co. which was executed by their decorator-artist Herr Albert Millet of Berlin. The design displayed a very distinctive mural in colour cement and marble relieved with aluminium strips.

Ideals for the ‘Ordinary Man’

The event that ran for twelve days attracted over 100,000 visitors. It is safe to infer judging by this magnitude of the crowd that the event received a huge turnout, leading the Institute to declare it a success. The exhibition was also greatly publicised and garnered extensive press coverage with photographs of the event being reproduced in several leading newspapers. The Times of India in its special issue dedicated to the Ideal Home Exhibition, published a nine-page feature covering details of the exhibition, various pieces on interior decoration, and advertisements by exhibitors and promoters.

“There is plenty of interest in this exhibition for the householder, the alert member of the public, the commercial man, the architect. To anyone whose interest lies in the social and technical (not merely verbal) development of the country, there is something of import here.”

-“Architects give Bombay a New Show” (Times of India, 3 Nov, 1937, p. 15)

The same issue of the Times of India also published an article titled “Furnishing Four Rooms for Rs. 2,000” that gave a cost break-down of each room in the exhibition. It stated an overall cost of Rs. 610 for the living-room with a large sofa, two easy chairs, two low bookcases, four small peg tables and a bureau; the dining room with its dining-table, six chairs, a sideboard and a silver cabinet was worth Rs. 312; finally, the bedroom comprising a dressing-table, a wardrobe, a tallboy, two divan beds, one chest of drawers, two side tables, two chairs and a stool makes a total of Rs. 485.[20]

For a poor or middle class household, earning between Rs. 50-60 per month with a rental of Rs. 10, those objects represented a month of income for simple pieces, and years for furnishing.[21] Only the upper classes and the Maharajas could easily afford the items on display.

In recognising this fact, Mr. B. G. Kher, Bombay’s Premier, in his address at the opening ceremony of the Ideal Home exhibition, provided staggering figures of the housing condition in Bombay. He pointed out that approximately 75 percent i.e. three-fourth of the vast population of Bombay lived in one-room tenements.[22] He expressed his regret for the lack of emphasis by the Institute and the scheme of the Exhibition on the most vital problem of Bombay – the housing of the working classes.

“In our search for ideal however, we cannot afford to lose sight of the practical realities of life. The housing conditions of the majority of people inhabiting the city are far from satisfactory.”

– B. G. Kher, Prime Minister of Bombay (JIIA, 1937)

More broadly, the architects of the IIA were reproached for promoting the ideals that were not in conformity with those of three-fourth of the population, “who rightly seek in Indian homes the use, comfort and beauty which their social, cultural and national aspirations as well as climatic conditions demand.”[23]

Having studied the changing ideas of the ideal home in twentieth-century Bombay, visual historian of colonial India, Abigail McGowan argues that lack of attention to working class housing at the exhibition reflects planners’ assumptions about the domestic lives of the poor. “Architects and town planners simply couldn’t imagine working class housing as ‘ideal’, let alone ‘homes’. Both because they were terrible spaces and places to live, but also because the working classes were understood by elites not to have ‘homes’ at all—just dwellings, without the emotional investment or material sense of comfort connoted by home,” professor McGowan explains.[24]

The exhibition was also criticised for the commercialisation of consumer goods that were displayed, comparing them to “window display or shop interiors”.[25] While crediting the ‘brave young architects’ for taking such an initiative, K. H. Vakil, who had raised the need for such an exhibition, claimed that it proved to be “least educative and least informative to the ordinary man.” His note in the Bombay Chronicle stated the exhibits were merely catalogue reproductions rather than a work of those considered to be the leading architects of the city, saying, “What is essentially the architectural difference between the present exhibition in the Town Hall and any similar shop interiors exhibition at any fourth-rate suburb in England?”[26]

Kapadia, however, emphasised the “educational value” of such an exhibition in its first attempt to introduce international standards in interior decoration and design “even for those who cannot afford such drastic reforms in the home”[27]. In his broadcast speech given towards the end of the Exhibition, the President of the IIA addressed these criticisms, stating “the educative importance of an exhibition such as that of the ‘Ideal Home’; for its purpose is to raise the standard of homes all around – not merely of those who can easily afford them, not merely for those who can afford them, perhaps, with more difficulty, but even more so of those to whom a small careless blunder in their homes, such as they are, maybe of life or death import.”

In Conclusion

Kapadia, who was re-elected as the President of the IIA for the third consecutive year, proposed to set up a Special Exhibition Committee in the Council. His scheme, however, to make the Ideal Home Exhibition an annual event in the city never materialised. Although, it inspired some smaller imitators, including the ‘Art in Home’ Exhibition organised by the Gujratee Stree Sahakari Mandal which included comforts and décor aimed at the middle classes, no other exhibition of this scale devoted to home décor was offered until well after Indian Independence.

Still, the exhibition had a broad impact. As Professor McGowan says, “the exhibition represented the trends of its time, coalescing them, and putting them on prominent, public display, bringing more visibility to modern ideals that were emerging around the city, among designers and manufacturers, in showrooms, through newspaper articles. It represented a very public display and celebration of modern ideals in interior décor.” The Ideal Home Exhibition of 1937, reflected “modern” ideals of health, hygiene, comfort, efficiency, convenience and most importantly beauty to the Indian home. It put on display for the residents of the city – irrespective of their class – the concept of apartment living and home decoration. It also communicated design standards for the modern home with the latest international styles engaged with modern technologies, which have today become the basic necessities of our modern lives.

Architect and historian, Professor Mustansir Dalvi points out that:

The exhibition “normalised the aspect of functional design, as opposed to stylistic or ornate styles, making it acceptable to the people at large. It exposed the majority to living spaces populated with modern furniture and fixtures, who in turn imbibed the culture and aspirations in their own lives, making functional or industrial design more appealing” [28]

The exhibition therefore was an important marker towards the future of the ideal home in an emerging, modern nation of nationally-minded, progressive citizens.

Acknowledgments:

Special thanks to Abigail McGowan, Professor of History, Associate Dean of Arts and Sciences, University of Vermont, for her rich contribution to our understanding of the subject.