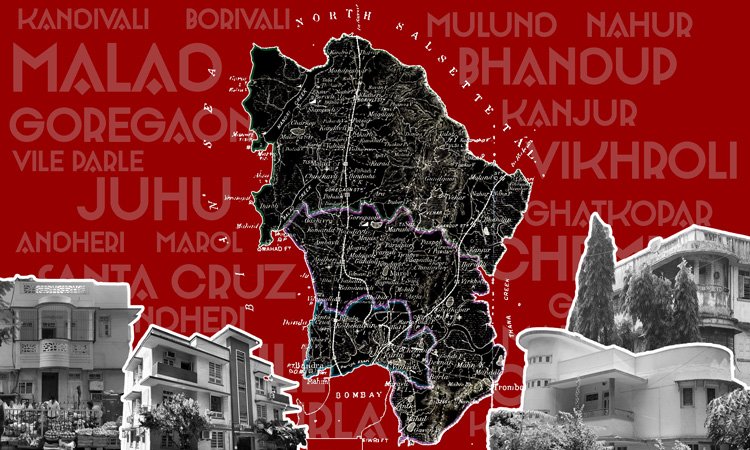

Art Deco, the dynamic and modern architectural style, arrived on Bombay’s shores by the 1930s, and became an enduring image of the city. The sophisticated and modern constructions along the Oval Maidan and Marine Drive, at the southern tip of the city, are some of its best examples. But there is a Bombay beyond south Bombay, and there is Art Deco beyond its southern end. By the 1960s, the limits of Bombay expanded northward, well into Salsette island [1], the region above the Bombay Island City. Art Deco travelled with it, modifying what it represented along the way.

The stylistic movement, which served as a stepping stone to modernism in India, created an array of possibilities not only in architectural production, but also an ideological advancement that marked radical changes in ways of living. With the availability of a new construction material – reinforced cement concrete (RCC) – immense possibilities opened up and inspired a new generation of architects to experiment with form, which dictated how the city would be shaped in the subsequent decades. Analysing this newly emerging socio-urban fabric of the suburbs opens up speculations of how Art Deco spread beyond the island city limits.

Through a reading of the suburban development between 1896 and 1960, this essay examines the influences that prompted Art Deco’s growth in the extended suburbs of Greater Bombay. It tries to analyse how the style, which was initially adopted by wealthy and affluent members of society, became associated with aspiration for the middle-classes who occupied a large part of the city and its suburbs.

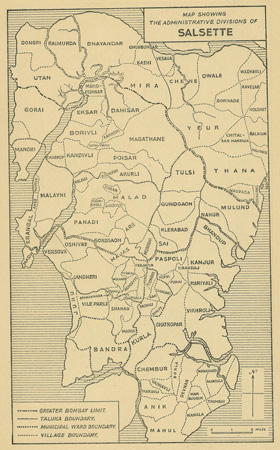

Surrounded by Ulhas river and Vasai creek in the north, Thana creek in the east, Arabian Sea in the west, and Mahim creek in the south, Salsette Island is often regarded as the “large northern neighbour of Bombay.”[2] Like Bombay, it consisted of the smaller village islands of Juhu, Versova, Malawani and Marwa at the western end, to name a few, and was also collectively named after its largest island.

Anchored into the urban histories of a few villages of the Bombay Suburban District’s Salsette and Trombay, this essay attempts a reading of Art Deco’s emergence in Bombay’s once northern neighbour.

Impact of the Bubonic Plague on Salsette’s Development

By the 1890s, the population of Bombay had reached close to a million, with migrants pouring in for economic opportunities from different parts of the country.[4] Textile and paper mills, dockyards, railway workshops, chemical industries, leather tanneries and pharmaceutical factories attracted people in great numbers. A working-class population, this section of the newly-forming society often could not afford train and tram fares or road commute. Consequently, a number of single-room chawls were built around commercial and industrial hubs in the Island City, like Byculla, Tardeo, Mazagaon, and Parel. These were immediately occupied to their maximum capacity, leading to a scarcity of clean water supply and sanitation facilities.[5]The Bombay City Improvement Trust (BIT), which was constituted in 1898 to oversee the challenges of overcrowding and sanitation in the wake of the Bubonic plague, focused on expanding towards the north to ease congestion in the south. According to the BIT’s plans to decongest Bombay Island, the western suburbs of Salsette like Juhu, Andheri, and Bandra were allocated to wealthier families. The middle and lower classes were left to either occupy the neighbourhoods that were vacated during the plague years; set up temporary camps in the Dadar-Matunga-Sion region; or migrate even further northwards.

This would ensure that employment opportunities in the east would attract mill workers and labourers, who would settle closer to their place of work. The west would be developed more residentially and commercially. This move was considered to be crucial to decongest former industrial areas and utilise agrarian lands for new construction.

These new industries and commercial opportunities not only attracted wage-workers, but also saw a rise in educated intellectuals and middle-class professionals like clerks, salespersons, bankers, managers and bureaucrats.

Salsette Deco

The diverse populace that migrated to these newly emerging suburbs carried with them ideas and aspirations of what their new homes should look like. The Ideal Home Exhibition of 1937 showcased a plethora of applications of new innovations in art, architecture and design, through drawings and photographs of buildings and its furnished interiors. Art Deco, with its sleek aerodynamic designs, smooth curves, geometric forms and understated relief work, was rampantly marketed.

In 1942, the Cement Marketing Co. of India published “Modern House in India,” a catalogue of building designs that were executed successfully in various parts of Bombay City and its extended suburbs. Subsequently, the cement company also introduced a range of brochures like “Designs for Modern Living,” and “Sixty Designs for Your New Home,” among various others which encapsulated the essence of a modern house, with modern amenities and spaces.

These periodicals, journals, and expositions created much fanfare around Art Deco, which was further bolstered by its prompt appearance in the design of picture palaces, as well as in the backdrop of movies. Art Deco’s design implications reached homes, not only through architecture, but also through furniture, home appliances, textile, jewellery, sculpture, painting, and cinema. It curated a standard of living deemed fit for the wealthy, upper-middle-class sensibilities, appealing greatly to a larger public’s aspiration. More significantly, RCC made it possible to construct mass housing schemes quickly. The relative convenience of construction, coupled with the easy adaptability of the style, manifested in several variations of the style across the city.

The Railway Line as a Node

Architects like G. B. Mhatre and Suvernpatki & Vora were commissioned to design buildings in the city as well as suburbs[10], which gave further impetus for Art Deco to travel to these areas. They took lessons from their successful experimentation of modern RCC buildings [11] in southern neighbourhoods like Kalbadevi, around Oval Maidan and Marine Drive, to the suburbs in Salsette, where the style gradually made its mark. The geographical linearity of Bombay and its suburban districts, along with rapid industrial expansion, also led to the development of new railway stations that transported raw material and personnel for construction in the south.

From the quarries of Kandivali that provided stone for filling up the Back Bay, to the industries of Mulund, the railway eased issues of transfer of goods. These “less important suburban stations” [12] became nodes around which the working class population resided[13], sometimes with their families. It served as a direct link for the transfer of tangible construction materials to the city from quarries at Kandivali, and intangible ideas of modernity back to the suburbs.

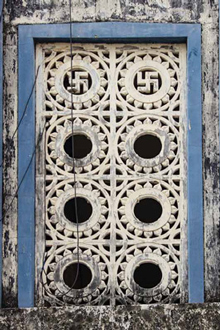

Magan Baug, situated near Kandivali railway station, is a fine example. It follows a layout of flats in a row along a single-loaded corridor. Two wings flank the central staircase turret, the centrepiece of this building. The balconies are bedecked with sunburst concrete grilles and are repeated throughout the facade of the building. The adoption of the swastika motif – a symbol considered auspicious across various faiths – in the concrete grille of the turret is an example of how Art Deco was locally adapted.

The Philanthropy of Stakeholders

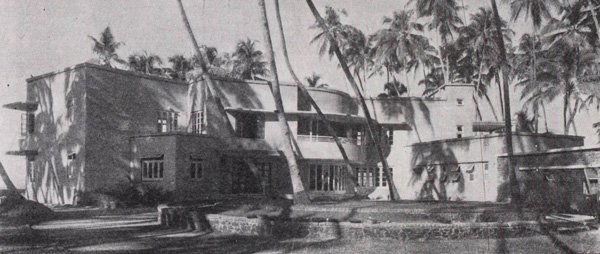

The gradual increase in the influx of people to the north also served as an incentive for entrepreneurial visionaries like the Wadias, Tejpals and Tatas to tap into the lucrative potential of lands in Salsette, especially the western neighbourhoods by the sea. Avenues for resorts and vacation houses to be built along the shore opened up. Prominent public figures of the time like M. C. Setalvad [14], the first Attorney General of independent India, and pathologist K. T. Gajjar [15] commissioned architects like Messrs. Master, Sathe and Bhuta, and Gajanan B. Mhatre, respectively, to design their homes in the balmy palm groves of Juhu. These bungalows used RCC, colourcrete and terrazzo flooring to create sweeping curves, continuous eyebrows and a sprawling floor plan that exuded elegance and opulence apt for their occupants.

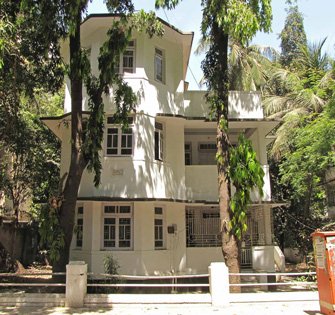

Parvati Niwas is an example of one of the few endangered Deco properties that has stood the test of time here. Built in 1947, it is situated within its own compound, with a sweeping curvilinear balcony that holds sunbursts in its concrete grilles. The rest of the facade is interspersed with typical Deco details like curvilinear balconies and the corresponding eyebrows, chevrons, sunbursts and speedlines.

These Deco motifs, often simplified, and sometimes crudely implemented in the suburbs, were adapted from the more extravagant ones in the southern parts of Bombay. As we move towards the eastern and north-eastern suburbs, where Art Deco emerged last on the heels of industrialisation, its influence wanes but is still discernible.

Industrialisation and Housing

According to the Bombay Development Committee’s Report, Mulund was one of these north-eastern suburbs that was allocated to industrial development.[21] With Asbestos Cement Company setting up a factory here in 1934, several other companies in the fields of paints, pharmaceuticals and metal works followed suit.[22] The presence of industries in the west of Mulund station prompted a spurt of development on that side of the railway track. The grid-patterned road network, reportedly commissioned by local zamindar Jhaverbhai Narottamdas in 1922 and executed by a German architectural firm Crown & Carter[23], abuts the western fringe of the railway station, facilitating ease of access to these places of work. The eastern fringe, on the other hand, continued to be largely agricultural and started to develop a few decades later.

Pramod Kandpile, a resident of Mulund, reminisces about the suburb in the late 1950s. Hailing from Panvel, his father purchased a plot east of the railway station in 1957. Largely swampy and full of trees, he recollects that this part of the suburb had a few prominent agricultural and fisherman family homes, with sloping Mangalore-tile roofs, vast stretches of farms, orchards and salt pans.

The Vision of a Garden City

The examples of Vile Parle, Mulund and Kandivali showcase that modern urban development in Bombay was largely concentrated around the railway station. But, a conversation with Nachiket Joshi, a resident of Chembur and an enthusiast of its history, presents surprising revelations about the suburb. The Chembur village was situated in the valley of Trombay Island, with hills on one side and an open stretch of land with Agra road on another.

These plots were sold to individual owners, who developed the houses themselves. Clem Cot, built in 1953, is a uniquely asymmetrical bungalow, with angular bay windows on one side and a long balcony on the other. The bay windows are framed by semi-octagonal overhangs or “eyebrows,” which run continuously along the front facade and turn with the building at the corners. The aesthetic, though rooted in Art Deco, plays by its own rules.

Unlike the Art Deco of the Island City of Bombay, the style in Salsette and Trombay imbibed local cultures and ornamentation that were used in more vernacular or traditional architecture.

It ranged between an eclectic hotch-potch of Art Deco elements like diluted streamlining limited to its curved facades and eyebrows, mixed with vernacular motifs on grilles and stucco work, as observed in Leela, an Art Deco bungalow in Juhu with floral motifs and a multifoil arch. Likewise, the sun motif in Magan Baug’s turret grille (see Fig. 2) is an actual representation rather than the usual variations of geometrically abstracted sunburst motifs.

Another important point of distinction between the Art Deco of Salsette and Bombay is the use of mass-produced grilles. Geometric grilles often appeared on several buildings of the extended suburbs, as opposed to the customised designs seen on buildings around Marine Drive and Oval Maidan.

While the grandeur of Art Deco may have faded as one went northwards, its elegance was retained in its streamlining, curvaceous facades, banding, staircase shafts and continuous eyebrows, making them obvious markers of Art Deco’s influence in BSD.

In Conclusion

The emergence of Art Deco in Salsette and Trombay is intricately interwoven with the history of urbanisation, and dynamics of several government departments and stakeholders involved in the development of the BSD. The Plague, the construction of railway stations and road networks, and a shift and diversification of industrial manufacturing boosted the population of the city and snowballed growth in the suburbs. These plans of expanding the city’s infrastructure coincided with the Art Deco movement that had already taken a solid form in Europe, America, and nearly simultaneously also in the Island City.

Before Art Deco’s inception, spread and popularity, the architectural styles that preceded it were mainly recognised for their application in prominent public buildings, like places of worship, universities and government buildings. The widespread popularity of RCC as a new and versatile building material further enabled Deco’s construction possibilities. It opened up a plethora of options in designs, and encompassed all building typologies.

In Salsette, the zoning of the suburbs, the diversity of the masses, and affordability often dictated the varying degrees in which Art Deco was adopted in different building types. The town planning initiatives for this district aimed at creating self-sufficient neighbourhoods with proximity to places of work and easing commute to other parts of Bombay, leading to the construction of suburban railway stations in the early decades of the 20th century.

The title of the essay includes the terms “affluence” and “aspiration,” in an attempt to describe the idea of Art Deco in the minds of people hailing from contrasting cultural backgrounds and sensibilities, and understand what made it so popular in people’s cultural imaginations. It challenges the notion of exclusivity of Art Deco to southern Bombay’s elite, and presents examples where the style thrived and was wholeheartedly embraced by different social groups. Its innate modernity allowed diverse groups to adopt it, thus making this fantastical style their own.

Pranjali Mathure for Art Deco Mumbai

Pranjali is an architect and researcher by profession, a photographer and graphic designer by passion. She is always on the lookout for details and calls herself a “parallel line addict”. She has a Master’s in Architectural History and Theory, from CEPT, Ahmedabad, and a B. Arch from Sir JJ College of Architecture, Mumbai. At Art Deco Mumbai, she reads, writes and designs for social media and outreach platforms.