The early 20th century in Bombay saw two distinct and major phenomena emerge – as the city became a prominent centre of film production, Art Deco simultaneously proliferated as a modern architectural style. Beginning in the new century, cinema and the city both developed and thrived, drawing from and informing each other in several ways. Bombay was a port city that formed the passage between India and the world. In the brief period of economic prosperity between the two World Wars, aesthetic practices like cinema and Deco enjoyed the proliferation of new materials, economies and ideas, with the opening up of the world. And Bombay remained at the centre of that in India. Urban industrial capitalism of the early 1900s brought about a modern way of being. Cinema, which emerged in the backdrop of this transformation, not only documented the pace of change in the metropolis, but also became “implicated” in it, as Ranjani Mazumdar has argued.[1]

In more ways than one, cinema “produced the city” – literally by shaping its infrastructure through production studios and sites, and symbolically through the creation of “ideas and ideals of the city”.[2]

Bombay frequently became the setting of the action in films, not only as a symbol of a modern metropolis, but also by virtue of easy access to its urban landscape while shooting outdoors. The Art Deco-laden avenues of Marine Drive and Oval Maidan often make an appearance (Yeh Hai Bombay Meri Jaan from CID, 1956; Rimjhim Gire Saawan from Manzil, 1977, later Badi Mushkil Hai from Anjaam, 1998). A tactile image of the city is constantly alluded to, even when the setting is not identified as being in Bombay. As Bombay cinema cast a wider net to become a “national” cinema, there was a deliberate attempt to set films within an ambiguous context. Even so, if the film was set in any city, it looked a lot like Bombay.

As one of the most popular mediums of entertainment, Hindi cinema became a means to convey social ideas of life and aspiration, most apparently dispersed through the narrative and screenplay, but equally if not more so, by the visuals in the frame.

Both the developments of Art Deco and cinema are aesthetic and visual movements that prompt various ways of seeing, carry their own imageries and codes, and become a popular canvas for (often non-verbal) expression.

This essay is an attempt to look at Bombay cinema through the lens of its spatial settings, to ascertain what they might have reflected about aspiration, aesthetics and life in the city during the Deco period (1930s-50s). To date, the city permeates into cinema not only as a representation of lifestyle, but also through its many lived and frequented spaces. The docks and Marine Drive become charged with the city’s class disparity in Deewar (1975), the streets are imbued with danger and violence in Satya (1998). More recently in Gully Boy (2019) and Gangubai Kathiawadi (2022), the interior lives of two marginalised groups is explored by way of two neighbourhoods in the city – Dharavi and Kamathipura. The city is a constantly expanding canvas that presents itself as a live backdrop for filmic action. The architecture and spatial settings of Bombay cinema, therefore, are far from incidental.

What identity of the city do we see forming in the early years of Bombay films? While Bombay’s docks and seafaces are immediately recognisable, the homes and interiors as they appear in films perhaps say a bit more about life in the city and the aspirations of its residents. As the metropolis evolved in the early 20th century, new ways of living caught the popular imagination, some of which also percolates into the films of the time. The homes we see characters occupy, and the lifestyles they seem to suggest, are deliberately constructed cinematic spaces that are often informed by an ever-evolving urban landscape.

As popular as they were, did these films shape public taste for the homes people lived in, or what they wished to project of themselves through their homes? What notion of the city can we draw from these films, and how do various characters engage with it?

Mise en Scene and the Cinematic City

The cinematic space is a constructed imagination, sometimes created through physical sets on a studio floor, sometimes in actual locations, and increasingly through virtual landscapes produced via special effects. The mise en scene, or how a frame in a film is designed, is a deliberate practice that lends meaning to the larger narrative of a film, and at times may even act outside of it. In 1930s Hollywood, sets for some of the biggest studio productions were also developing alongside prevailing architectural practices at the time. As cinematography became more advanced, the sets needed to improve too as anything in front of the camera would be clearly visible in the frame. It is at this time that American architects became more involved with film production, making up for “nearly ninety-five percent of all Hollywood art directors” at the time.[3] Art Deco became part of the distinct “Hollywood style”, appearing in filmic images across genres, from melodrama to comedies. Cedric Gibbons, the art director for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (the studio giant that also commissioned the eponymous Art Deco picture palaces in Bombay and Calcutta) visited the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, where the Art Deco movement originated in the world. It was apparent his designs for film sets were heavily influenced by what he saw there.[4] As studios received letters from fans asking for details of homes they saw in the movies, including photographs and floor plans, it also became apparent these designs did not simply remain as settings for the film’s narrative. Popular films have frequently been recognised as a vehicle for consumerism and a “merchandiser of goods”, and the same seems to have applied to how homes should be designed and decorated.[5]In India, these extrapolations are harder to make, with little remaining of studio documents from the 1930s, details of production labour and even the films themselves. Of several issues of the popular Filmindia magazine, one lone question seems to have been about “art direction” in Bombay films.[6]

Upon observation, however, there are inferences to be made about how the lifestyles of characters were depicted via film sets.

In Nirmala, the setting of the action is frequently the interiors of the home, notably the respective living rooms of protagonists Ramdas (Ashok Kumar) and Nirmala Devi (Devika Rani), where they entertain friends and host gatherings. The living room, an amorphous space within the home which is neither the private bedroom nor the public front yard or porch, becomes cemented in 20th century modern homes as a semi-private parlour for leisure and recreation.[11] Both Ramdas and Nirmala’s living rooms are decorated with streamlined Art Deco furniture, patterned wallpapers, lace-trimmed drapes and indoor plants – a page out of popular furnishing advertisements at the time or brochures from the Ideal Home Exhibition held in Bombay in 1937.[12]

The telephone, a modern amenity gradually entering the homes of upper middle class Indians, is placed in this room as well, and becomes instrumental to the exchange of information in the film’s plot. It is also through popular films that the telephone is being advertised to audiences as an amenity they should purchase, with figures like Padmadevi (star of the first Indian colour film Kisan Kanya) doing print commercials for the Bombay Telephone Company.

As costume, the women frequently wear sarees, a traditional attire, but made with light and airy materials, aiding their mobility as modern women participating in the world. The blouses too depict more “risque” styles, with shorter sleeves and playful patterns.[13] “Sometimes the modern is shown to be appealing and then repudiated after we’ve enjoyed seeing it,” points out Rachel Dwyer, scholar of Indian culture and cinemas.[14]

In both Bhabhi and Nirmala, the narrative engages with the predicament of modernity, battling traditional social mores, the fear of scandal, and the gendered makeup of the domestic realm. Nirmala, a modern, educated woman who marries for love, gives up her domestic bliss over a superstition that causes her to believe she is cursed and cannot bear children. Modernity, therefore, is constantly interpreted as an interplay of the desirable and the dangerous or unfavourable.

Urban life forms the backdrop to the narrative in these films, with characters interacting with neighbours in the flats next door, shuttling around the city in modern cars and automobiles, attending co-education universities, and more. The city becomes a “distillation of cinematic modernity”, with the characters engaging with its built form and corresponding lifestyle in various ways.[15]

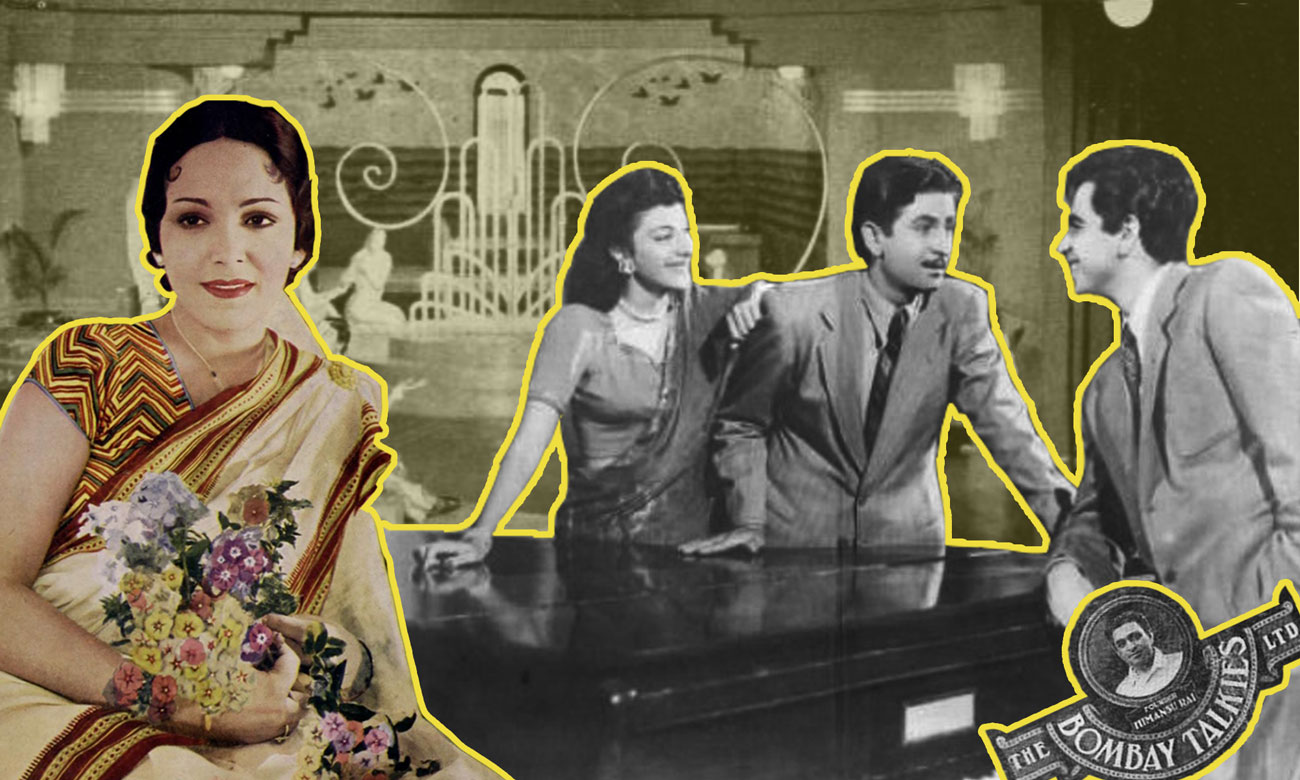

Interestingly, in a fictional show about the world of the Bombay Talkies studio, Jubilee, released in 2023, the backdrop and settings of the studio and its offices are unambiguously Art Deco. “We go into the history of the character, before we start designing,” says Mukund Gupta, production designer for the show.[16] Speaking of Srikant Roy, the character loosely based on Himanshu Rai (founder of Bombay Talkies), Gupta says: “He has been educated in Europe. He’s been exposed to the glamour, elegance of architecture. So if he is coming down to Bombay and establishing his studio, he would like to have that kind of elegance in his office too.” In reality, the studio was situated in a sprawling Neo-Classical style mansion, leased from industrialist F.E. Dinshaw.[17] But its reimagining as an Art Deco structure, owing to Srikant Roy (or Himanshu Rai’s) modern experiences and exposure to a certain aesthetic, is not unfounded. Indeed, Bombay Talkies operated with a logic of internationalism, with a cosmopolitan school of German emigres forming its core group of technicians.

The Modern City and its Networks

Much like in real life, modernity emerging from the cinematic city also spills over into adjacent hinterlands. The train becomes a major symbol which bridges the city with the countryside, carrying with it notions of mobility and blurring the boundaries between the “modern” city and the “pre-modern” village. Miss Frontier Mail (1936), a swashbuckling action thriller starring Fearless Nadia, for instance, is set between Bombay and an unnamed nearby town. Nadia plays Savita Devi, who also goes by the moniker Miss Frontier Mail, named after her incredible agility (she moves as rapidly as the Frontier Mail, the train which started in 1928 and ran daily from Bombay to Peshawar in pre-partition India). Savita must rush to Bombay to rescue her father, who has been falsely accused of committing murder. Upon reaching Bombay, she unravels a more complicated nexus of thugs trying to grab land for various development projects. The city, therefore, also becomes a place of temptations, corruption, and amoral practices, exemplified by Savita’s encounters, and also seen more prominently in later works of RK Films (Shree 420, Awaara), and Nav Ketan’s Bombay noirs (Baazi, CID).

The interaction between the city and the hinterland is an ongoing exercise. The action in Miss Frontier Mail flits seamlessly between the two locations by way of various modern modes of communication – the train, telegram, even a radio telephone!

Her living room, which again becomes the site of much of the action, sports a stylish look with marble floors in a distinct zig-zag pattern, frozen fountains on the doors and artfully placed statues. These are not the typical interiors of homes one would see in films set in the hinterland or village (Bombay Talkies’ Achhut Kanya, for instance, looks very different), which would otherwise have sombre mud walls and sparse furnishing. Savita Devi, aka Miss Frontier Mail, however, is a radical modern figure. Back home, Savita lives in a bungalow lavishly done up in the Art Deco style. A woman whose dexterity is compared to a train, who practises boxing in a bodysuit in the gymnasium attached to her house, wields a pistol, and is constantly called upon to beat up the bad guys and save the day.

Her home, therefore, is a reflection of her dynamic, fast-moving life, even if it isn’t in the city proper. Much like in this cinematic world, the real-life networks between the city and neighbouring towns and villages, via train lines and other modern channels, also led to the movement of modern styles like Art Deco into other centres, as evidenced by its presence across India’s expanse – from Patiala to Thrissur.

“Beautiful Homes” and What they Tell us

As much as popular cinema is about the spectacular, it draws on a notion of reality (albeit with some glamourised creative liberties). The lives we see people lead in the movies is in part drawn from a larger notion of what life should look like, especially in an increasingly consumerist society with the turn of the 20th century. The homes and lifestyles we have seen in the three films so far are an unambiguous depiction of certain class positions and aspirations – Nirmala and Ramdev live in bungalows with surrounding gardens, have chauffeured cars, and are Master’s students at the university; Kishore lives in a modern flat – modest when compared to the bungalows in Nirmala, but he is a scientist and a man of respectable morality; Savita lives in a bungalow in a smaller town and serves, somewhat, as the local matriarchal figure – notably, her father is a station master, employed with the British India government in one of the early white collar jobs under the colonial administration. They occupy various stratas of the Indian middle classes, with respectable jobs, education and carefully curated homes. In reality, the consumerist and lifestyle opportunities for much of the audience watching these films may have been limited. “But they would be creative, so [they] would adopt a hairstyle or a small item,” says Dwyer. “Buying Lux [soap] was to emulate a star, but home furnishing may have been less available,” she adds.[18]

Even so, the preoccupation with the home and interiors is one being reflected through various channels in the 1930s. The Times of India carried a special “Beautiful Homes” supplement with detailed ideas for how one should decorate a modern home. Suggestions for “a novel writing desk”, “a grandmother clock”, “stained glass windows” or “radio gramophones” abound in these pages. If the Art Deco style, seen in the exteriors, was symbolic of the embrace of a new epoch – the image of a well-travelled and dynamic modern Indian – the interiors too were similarly transformed to reflect the exploration of a “global modernity”.[19]

The emerging urban middle class defined itself first and foremost by participating in a culture of consumption that reflected their status. Their homes, as depicted in the films of the time, were decorated with curios (perhaps picked up during travels overseas), streamlined furniture, and ample space for privacy and leisure.

As the decades pass and the scale of film production escalates, so does the detailing in sets. The homes of the wealthy become all the more ornate, overseas locations (or at least frequent mentions of them) become common – the cinematic imagination, and with it the imagination of the viewer, is indulged with visuals of a newly independent India interacting with the world, so to speak. Mehboob Khan’s Andaz (1949) is a fine example of this. Neena (Nargis) is the daughter of a wealthy businessman who befriends Dilip (Dilip Kumar), who although respectable, is not as rich as Neena. A love triangle ensues when Neena’s fiance Rajan (Raj Kapoor) returns from London. One of the biggest successes of the year, Andaz engages with questions of class, gender, and respectability. Its settings say much about the characters. Neena’s home is opulent and makes generous use of Art Deco furniture and aesthetics. Her room is high-ceilinged with a queen-sized bed in the middle, and drapes that are opened each morning by a handmaiden, who also fetches her tea in bed.

There are several different rooms in the mansion, as homes of the wealthy in Hindi films often do. Each room has a function of its own: a living room with an extended outdoor patio, a study/library with a fireplace, a grand staircase that showcases the expanse of the two-storied home. Notably, the piano becomes a central object in the living room, around which much action takes place, including society parties. This is in keeping with popular notions of sophisticated decor, with the “Beautiful Homes” supplements carrying several advertisements for pianos, especially designed for Bombay’s tropical climate.

The piano is a symbol of status and culture, as much as various other leisurely activities Neena participates in – lawn tennis, horseback riding, and playing hostess at lavish soirees at her home. “Travel, beauty, fashion, health and fitness” are a “range of consumerist and leisure practices” the new middle classes seem to enjoy and define themselves by, which comes to a head in later years with economic liberalisation.[20]

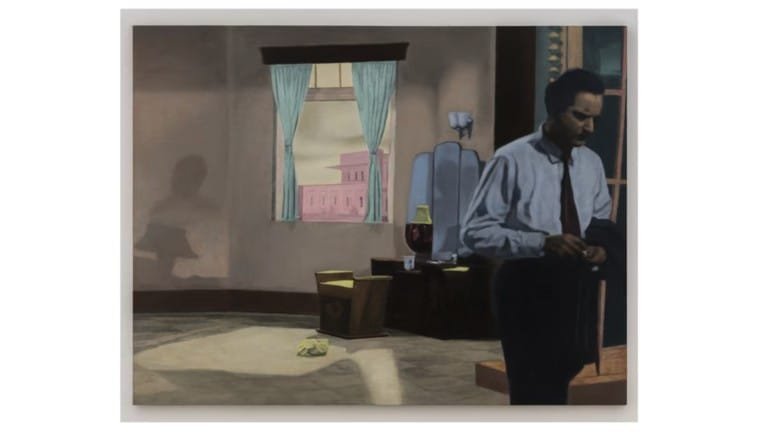

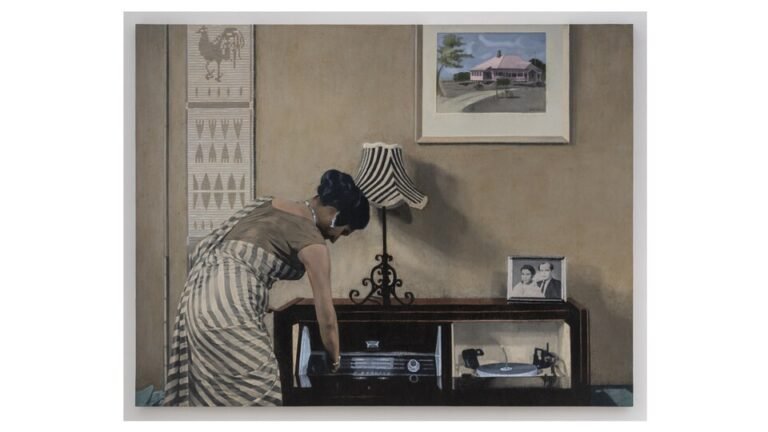

Slices of this lifestyle are reflected in artist Atul Dodiya’s recent work ‘Dr. Banerjee in Dr. Kulkarni’s Nursing Home and Other Paintings 2020-2022’, which demonstrates the familiar domesticity of Hindi films post independence. Through paintings, Dodiya freezes the frame in several notable Hindi and Bengali films from the 1950s onwards, presenting an opportunity to mull over objects in the frame.

“I want people to see not just the character, but also the background. I find this mix of diverse, hotch-potch combinations of furniture and other elements in the room interesting,” Dodiya says about his choice to paint these specific film frames. These domestic spaces reflect an interesting history of use and lives lived. “Cinema aside, in our country, our feelings about family are different. I still would not throw out something my father must have kept on his table. I am concerned with people’s emotions around the objects they collect,” Dodiya adds, lending a dimension of familial history and sentiment to acts of consumption.

The paintings capture an “era when habitation occurred in a variety of forms reflecting family structure, gender roles, class, and migration,” writes Mustansir Dalvi in his review of the work. “Each typology comes with objects that give context to those spaces,” he adds. Polished radiogram cabinets, dressing tables with full-length mirrors, photo frames, flowerpots, and more make up some of these objects. Dalvi describes this “stable domesticity” as taking shape around these objects which become heirlooms collected over the years, as people move in, out of and around Bombay. “An archive of the lost years between independence and liberalisation”, Dodiya’s work exhibits the potential of looking at cinema as a visual archive of life in the city.[21]

In Conclusion

By the 1990s and the turn of the new century, the image of the city in films (whether Bombay or otherwise) is a vastly different one. But cinema becomes a visual bank of memories that aids in charting this transformation of the city and life of urban Indians. It contains within itself an untapped archive of the city and its lived spaces. These filmic visuals of the city lend to a collective imagination of urbanity.

In Bombay, at least, it is difficult to ascertain where cinema ends and the city begins. These are intertwined threads that push and pull, constantly drawing from the other. If film reflects some notion of real life, then life in the city too takes on a cinematic form, with ordinary moments like sitting at Marine Drive or catching a crowded bus in the monsoon becoming “filmy”.

Through the 1930-50s, by way of narratives about families, love, domesticity, the films engaged with larger notions of India’s emerging modernity, in the backdrop of a raging nationalist discourse before and after independence. The spaces in these films, whether the home or the world, are charged with meaning. Whether the modest sets of the Bombay Talkies social films, or the opulent scale of Andaz, the location and settings embody lived experiences and emotions as much as they are “environments or mediums that carry bodies”.[22] The homes and spatial settings are not merely passive backdrops, but deliberately constructed imaginations of life itself. Even if much of the audience viewing these films may have lived very different lives – as in the case of those consuming the “Beautiful Homes” newspaper supplements or the Ideal Home Exhibition – it did create images of what one could aspire to or at least what a certain mediated version of modernity could look like.

The Art Deco style is an active participant in this image making exercise, being deployed as a symbol of modern ideas, cosmopolitanism, and life in an emerging metropolis. It becomes a means in which to engage with the city, whether in films or otherwise.

As cinema and the city evolved in tandem, its corresponding life, ways and idiosyncrasies became enmeshed, creating images and messages that carried far beyond Bombay’s borders.

Suhasini Krishnan for Art Deco Mumbai

Suhasini is Head, Outreach & Content at Art Deco Mumbai. A writer and editor, with an academic background in Film Studies and History, her research interests lie in cinema, modernity, and the making of an urban city.

Header image: Digital illustration by Pranjali Mathure, for Art Deco Mumbai