This could be the script of a movie. The year is 1920. Two teenage brothers – one to be given up for adoption – fearing the prospect of being separated, run away from their village in Ratnagiri and come to Bombay. They find work in the city as canteen boys, carpentry assistants, become carpenters, and eventually, interior designers, woodwork artistes and architectural planners. In their early years, they also find themselves teaching art to the children of their Girgaum chawl, allowing them an additional income to live comfortably and educate themselves further.

In 1939 they establish their design company, Nambros, after excelling at their chosen professions. The ailing elder brother, Vishnu Moreshwar Namjoshi, relocates to the drier climate of Indore and becomes a highly respected furniture and interior designer (his son Anand continues to run the company successfully). And the younger brother, Waman Moreshwar Namjoshi, remains in Bombay and achieves extraordinary levels of excellence as a cinema theatre designer. And vanishes into history, despite creating some of the most iconic Art Deco cinema theatres in India.

This tiny little narrative above has not been easy to research. I had started on my journey of photographing and documenting India’s vanishing single screen cinema theatre heritage in January 2019. The name Waman Namjoshi, better known as W.M. Namjoshi, kept showing up on my travels. He was often mentioned by the owners of brilliant Art Deco theatres, as the ‘architect’ of their spaces. My desperate efforts to unravel his mysterious life eluded me for almost four years. None of my architect friends had ever heard of him, no amount of research, digital or otherwise, yielded any results. I found brief references to him in a book called “Bollywood Showplaces” (Vinnels & Skelly, 2002) and another in an interview with Nazir Hoosein (Liberty, Bombay) for Art Deco Mumbai Trust. And some mid-century newspaper clippings, with very brief references.

During the brief inertia of the first Covid lockdown in 2020, I located a very large number of Namjoshis on the internet and called almost 75 numbers, asking whether they were related to W.M. in any way. The answer was always in the negative. One number and address, however, remained elusive. I had found on Google, a design firm in Indore owned by a Namjoshi. On a visit to Indore in 2020, I located the address and found it locked, and the two listed phone numbers went unanswered.

In 2022, when Atul Kumar (Founder Trustee, Art Deco Mumbai) asked me to create a presentation for his Art Deco Mumbai loyalists, I decided to do it in two parts. The first showcasing my journey beyond Bombay, looking at the Art Deco cinemas from the 1930s-1960s in small town India, illustrating the concept of aspirational architecture, and how the style had found its way into the interiors and the popular culture of our country. The second part was to be my desperate attempt to locate the genius called W.M. Namjoshi.

While organising my presentation, on a whim, I called that number in Indore again. A cheerful male voice answered, and I posed my oft-repeated question for the 76th time to the 76th Namjoshi.

“Good morning, sir. Are you related in any way to W.M. Namjoshi?” I asked. “Yes, he is my late uncle. He was my father’s younger brother” answered the voice.

I had located Anand Vishnu Namjoshi, V.M. Namjoshi’s son, and W.M. Namjoshi’s nephew. And suddenly, my perseverance had paid off.

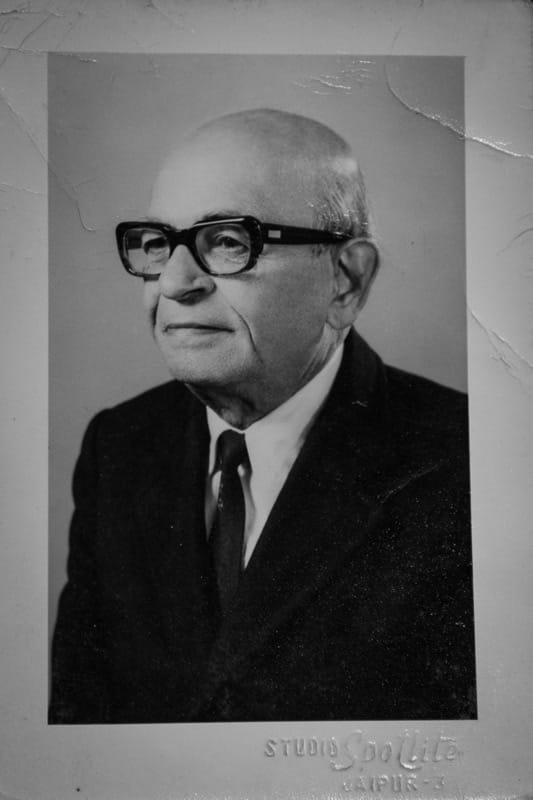

Anand Namjoshi told me some wonderful details of W.M. Namjoshi’s life, and he introduced me to Shilpa Sathe, W.M.’s granddaughter and an architect herself, from whom I managed to learn about him even more. Above all, while W.M. always considered himself to be an interior designer, he also made the architectural plans and designed the facades of some of his theatres. Which is probably why the confusion of his professional identity persisted, many people thought he was an architect.

Art Deco had started creeping into Bombay’s architectural landscape as early as the 1930s, seen often as relief motifs on residential and commercial buildings in the Colaba-Fort area of South Bombay. Regal Cinema heralded the formal arrival of this style, in 1933, and is regarded as one of the first Art Deco cinema theatres in India. Closely followed by Metro and Eros (1938), which took the style to a spectacular level.

British interior design companies in Bombay start bringing this style to the homes of the elite. Vishnu and Waman Namjoshi are deeply involved in these creations, working as carpenters and furniture designers for E. Wimbridge & Co. and Mackenzie & Co. And later, after V.M. relocates to Indore, W.M. works with The Army & Navy Stores. Inspirations are taken from contemporary design magazines and trade fair literature imported from USA and Europe. Creating modern international spaces for a newly emerging style demographic in Bombay.

By 1942, Namjoshi has designed the interiors of two cinema theatres, Chhaya Mandir & Kala Mandir, in Solapur. Which show the quiet emergence of some of his iconic design motifs and acoustic considerations. In the mid-1940s, he is introduced to Keki Mody and hired to renovate and redesign the interiors of Minerva (Calcutta) and Empire and Excelsior (renamed New Empire and New Excelsior post-renovation, in Bombay), and Strand (Bombay). Minerva has since been demolished and no photographic evidence exists of the interior. New Empire stands closed, but the immaculate interiors and the clear confidence of Namjoshi’s style is visible till today. New Excelsior has been renovated into a modern theatre. Strand was erased many years ago.

In 1944, he gets hired by V. Shantaram to be the Associate Set Designer and Furniture Designer for his film Parbat Par Apna Dera, in which one can see his work in all its black and white glory. Namjoshi and Shantaram would collaborate again on two more movies, Parchhain (1952) and Teen Batti Char Rasta (1953). He starts work on Phul Cinema (1947) in Patiala, a spectacular Art Deco structure, restored fully in 2018 and still running successfully 75 years later. Shantaram introduces him to Habib Hoosein and is hired to design the facade and interiors of the staggering Liberty Cinema (1949). And over the next decade, he adds Golcha (Delhi), Kiran and Jagat (Chandigarh), Maratha Mandir, Naaz, and Minerva (all in Bombay), Uma Chitra Mandir (Solapur), and a large number of non-Deco theatres, culminating in 1976 with Raj Mandir (Jaipur), regarded as one of the three most beautiful cinema theatres in Asia.

He also designed the existing premises of the film studio, Rajkamal Kalamandir, for V. Shantaram. Namjoshi had very long associations with his clients; he worked on multiple projects for Keki Mody, Habib Hoosein, Shyam Lal Gupta, Mehtab Chand Golcha and V. Shantaram. Kushal Surana, (Raj Mandir, Jaipur), Bharat Bhagwat (Chhaya, Kala & Uma Chitra Mandir, Solapur), Kiran Shantaram (V. Shantaram’s son and owner of Rajkamal Kalamandir), Sanjeev Gupta (Phul Cinema, Patiala) and Shilpa, his granddaughter, all remember him as being a meticulous and perfection driven artist. Kushal Surana recalls how W.M. would build entire sections of Raj Mandir, and demolish them because he wasn’t satisfied with the results. And rebuild them!

Unknowingly for the most part, I had managed to photograph 18 of his 34 cinema theatres. Fourteen have been demolished, a few after I managed to document them. There are two theatres in Mumbai that are still pending; permissions have been elusive, despite over four years of perseverance.

Curiously, since I have photographed his very first cinema theatre (Chhaya 1938) and his last (Raj Mandir 1976) and 16 in-between, I have observed an evolution of his style, and the perfection of the recurring motifs and preferences of the artist. The frozen fountains were one of his favourites, as were the circular relief lighting alcoves, and the layered walls and ceilings of his auditoriums. The layered walls and ceilings evolved from his obsession for acoustics, and provided him with an unusual way of creating lighting dreamscapes with concealed bulbs, highlighting the shapes, outlines and relief work, and successfully creating tremendous depth in these spaces. His spaces look cavernous and are softly and shadowlessly illuminated. And with his love for deep pile carpeting, the result is a lush and rich atmosphere.

He had an odd little signature motif that I found in several of his cinema theatres, four-pointed or five-pointed stars, sometimes backlit – you will see them on the facade of Raj Mandir, and sometimes even in his non-Deco creations. He was also one of the early patrons of 3D glass sculpture art works, and worked extensively with Divecha Glass Works (Bombay) for decades. Creating pastoral scenes, with apsaras and fawns and water bodies. And his bevelled glass and wood chandeliers, visible across his career.

But the most subtle and often overlooked facet of his skills sometimes get lost in the grandeur of his spaces. Since his earliest skill was carpentry, the woodwork in his spaces is truly exceptional. I am told by Shilpa that he created the woodwork himself, from the plans to the actual execution, with his trusted team. And it is exquisite, for the design, finish and longevity of his commitment.

But what I find most intriguing is that he must have been 26 years old when Regal Cinema was built, and while Metro and Eros, the business district of Fort, and the residential precinct of Oval Maidan, soon set the bar at impossibly high levels of excellence, he seemed impervious to those trends and quietly carved out his own elegant and awe-inspiring style. Namjoshi’s work, I believe, is less Art Deco, and more Streamline Moderne. His work stands out for its simplicity and for the use of shapes and lighting. I remember joking with a friend of mine that his design style seems inspired more by radiogram and furniture design of the era, which was something he was probably more familiar and comfortable with!

Above all, I am grateful to the cosmos for this opportunity and the good luck in my endeavour of tracking down the Namjoshi enigma, and being able to share the life, however briefly, of this brilliant artist. I believe it is important for artists like him to be venerated and remembered before an entire era gets wiped out, because we gave it no attention.

Hemant Chaturvedi, for Art Deco Mumbai

Hemant Chaturvedi is an ace cinematographer in the Mumbai film business since 1985. He has worked on films like Ram Gopal Varma’s Company, Vishal Bhardwaj’s Makdee and Maqbool, and Aparna Sen’s 15 Park Avenue. In 2015, after filming 12 feature films and over 700 television commercials, he gave up his successful career as a cinematographer, and returned to full-time still photography. As part of his photography oeuvre, he has been documenting old cinema theatres and British-era cemeteries. In 2021, he directed and produced Chhayaankan – The Management of Shadows, the first and only documentary film about cinematography in India.

Header Image: The stunning ‘Academia’, the mini theatre at Liberty Cinema, Mumbai. Photo Courtesy: Hemant Chaturvedi