After many years of biding its time under the care of the church, it was finally granted landmark status in 2017, allowing it to once again become part of contemporary society by repurposing the structure to meet recreational and business needs of the neighbourhood. Once this ever-changing edifice reaches its final avatar, as there are yet a few hurdles to overcome, the neighbourhood will hopefully be bolstered by the countless opportunities the El Rey is likely to manifest, and lift the Ocean Avenue corridor out of its declining economic prospects. The following essay maps the rise, steep fall and hopefully a glorious rise again of this former Art Deco theatre.

Are there lessons to be learnt from El Rey’s journey that one can apply closer home in Mumbai? Can comparisons be drawn between the two cities and their theatre culture? Can Mumbai’s Art Deco picture palaces, which have seen a similar trajectory, help understand what could lie in store for El Rey? This essay is an attempt to explore some of these questions.

The History of El Rey, the ‘Movie Palace’

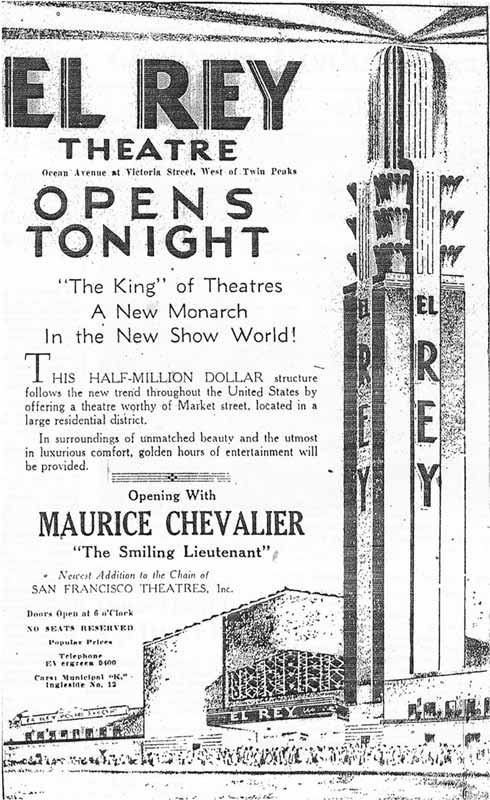

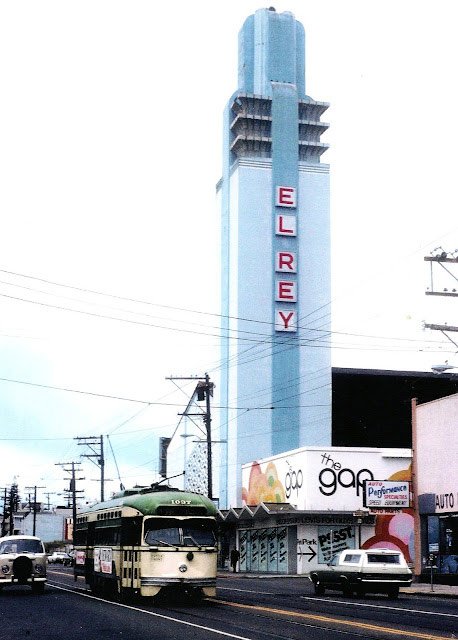

The Bay Area mise-en-scene in the late 1920s was marred by uncertainty and dire prospects, with the beginning of the worst economic downturn in the history of the industrialised world – the Great Depression. What’s more, the interwar period, though temporarily peaceful, added to the general sense of doom that had taken over the world at large. Although the West Coast of North America had taken on an amoebic form, it still lacked much in comparison to the older and established East Coast cities. Enter El Rey, a theatre built in San Francisco’s suburbs rather than the more notable downtown area. The San Francisco Examiner, one of the four major daily newspapers in the Bay Area, called it a ‘movie palace’ at the time of its opening.[2] Fitting was the name ‘El Rey’, meaning ‘The King’ in Spanish, paying tribute to California’s colonial history which led to many cities and structures bearing Spanish names.“The more effervescent iteration of Art Deco in San Francisco gradually succumbed to Depression-era austerity and the adoption of a more sober aesthetic embodied in the stripped-down public buildings.” [5] The El Rey theatre was a manifestation of this change in architectural style.

In the wake of the decline of Vaudeville (and similar forms of theatrical entertainment) after World War I, the need arose for purpose-built cinemas, suited to motion pictures. There was no longer a requirement for backstage areas or green rooms in these structures. Cinemas, often converted into talkies from theatres, were emerging in urban cities around the world, as new, modern forms of entertainment. An example of this transformation can be traced to Bombay’s Royal Opera House, which started out as a live production theatre, with its lavish baroque façade, gilded interiors, and red carpets. It soon had to redefine itself to accommodate motion pictures in 1935, around the same time when modernism in the form of Art Deco laid its roots in the port city. San Francisco’s theatres have also seen similar trajectories — one could say, evolution with the times is an inherent quality possessed by these picture palaces.

Theatre Moderne with Bold Façades

Theatres were famously designed with a focus on their exterior façade. Architectural firms specialised in theatre design which created a diverse style and fast-tracked the evolution of spaces necessary in theatres.

Charles Lee, an American architect, and distinguished theatre designer famously said: “The show begins on the sidewalk”.[9] Lee hints at the need for an extravagant façade and luminous entrance by way of the marquee extending over the sidewalk.

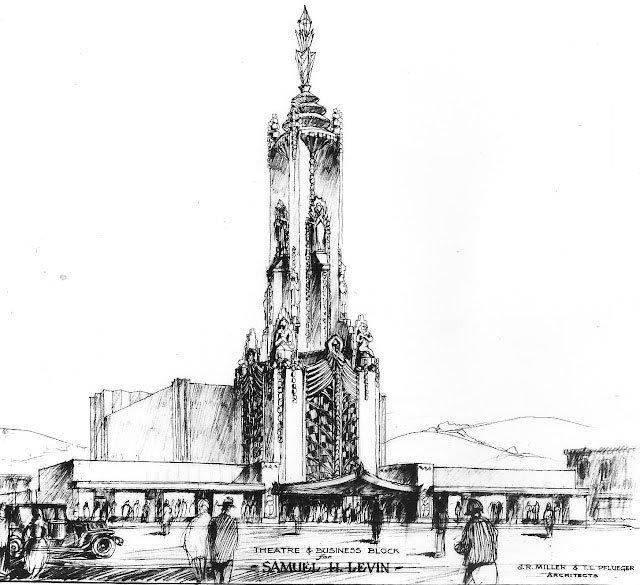

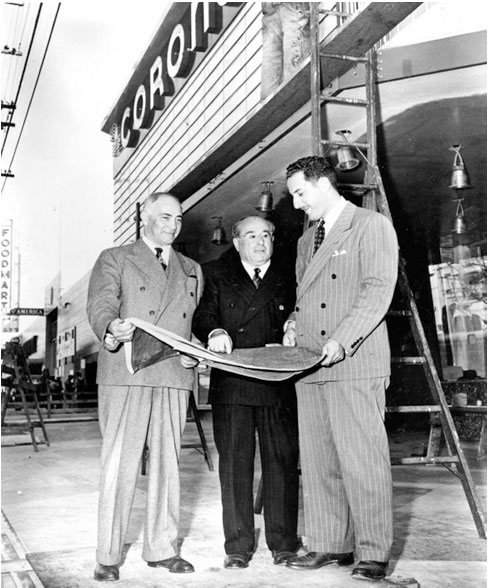

El Rey was designed along these lines by Miller & Pflueger, for theatre owner Samuel H. Levin in 1930, with a vision of building a theatre that was larger than life and would be the crowning achievement of Levin’s career. Born in 1886, Levin grew to be a local theatre mogul who capitalised on building numerous theatres on transit lines, in fast-growing but still outlying parts of San Francisco. After a decade of establishing a theatre circuit in the Bay area, he planned to build an even more extravagant theatre. Even though Levin had to compete with already established picture palaces in San Francisco, he must have known El Rey was going to be ground zero for whatever entertainment the suburbs needed, all thanks to its unexpected yet lucrative location.

Likewise, the magnificent Eros Theatre in the Churchgate area, the first Art Deco district in Bombay, hosted many entertaining nights consisting of not only movies, but also soirees and cocktail parties with a spectacular view of the newly developed Back Bay area, held at its high-end open-air restaurant. The theatre was one of the first of its kind in the East, giving the city several new modes of recreation, from stage theatre to cabaret nights and performances from an all-female band from England. Both El Rey and Eros Theatre doubled as mixed-use commercial structures during the day, providing spaces to conduct not-so-glamorous businesses. With the strong patronage of Samuel Levin for El Rey and S C Cambata (the Parsi businessman who commissioned the theatre) for Eros, both theatres elevated entertainment expectations in the cities they were located in. Levin, ever the businessman, made sure most of his theatres had storefronts or were a combination of theatres, auditoriums and business blocks. This is yet another point of convergence with theatres in Mumbai, like Regal Cinema, Eros and Liberty, which also followed a similar business model and were constructed as mixed-use complexes rather than as singular theatre spaces.

Although El Rey was near a tram line, its location in the suburbs was potentially limiting in terms of drawing in crowds, not unlike the Aurora Theatre in Matunga, which was similarly located on the outskirts of Bombay. On the flipside, however, there was hope that this unique location would allow it to cater specifically to the neighbourhood and attract patrons from nearby areas. The same could be said for Aurora, which was fated to cater to the growing resident population of immigrants in Matunga and surrounding areas, due to its unique location, a theme this essay will explore later.

In an article published on the opening night, the San Francisco Examiner stated: “[The El Rey Theatre] is destined to take a high place among San Francisco’s most important theatres, by offering a theatre worthy of a downtown location, though it is located in a residential district.”[10]

El Rey, a neighbourhood theatre masquerading as a movie ‘palace’ away from the resplendent downtown Bay area, fulfilled several such roles, serving local residents who did not want to travel too far, fashioning itself as ground zero for emerging commercial districts, attracting small businesses, and being a catalyst for real estate development in the region. Its colossal size and style of architecture made it the neighbourhood’s identity and a symbol of progress that was to come.

Jazzy Interiors and the Gap Store

Developed on five vacant plots, the primary façade of the structure consists of four parallel volumes, with the gabled roof theatre lobby at the centre. Next to it is the dominating tower which is flanked by two flat-roofed retail wings. The architect’s final rendition cements his intention to adopt a simple approach in terms of ornamentation on the façade, relying on scale, mass, and lines to create a new language in the yet-to-be monikered Art Deco style.

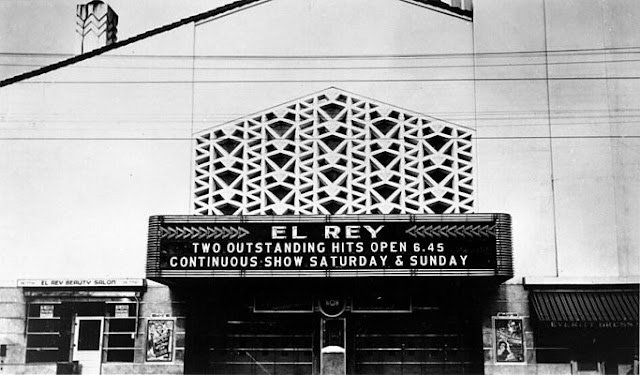

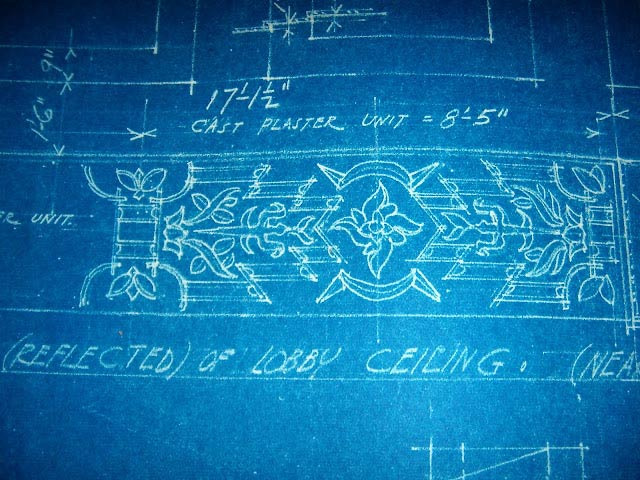

With an opening advertisement in the San Francisco Examiner captioned ‘The beacon’s Rays will guide you’, coupled with the enticing klieg light synonymous with the golden age of cinema in Hollywood, it boosted the theatre’s growing popularity. The sprawling theatre opened on November 4, 1931 with the capacity to seat 1,831 patrons and ran the musical comedy The Smiling Lieutenant, starring Maurice Chevalier. A bright, gleaming marquee above the entrance illuminated the sidewalk, serving as a landmark and distinguishing the theatre from other businesses for passersby. The neon signage with the name of the theatre hung high on the colossal stepped tower, and served as the centrepiece for an upcoming neighbourhood. Pflueger, still experimenting with streamlined modern style, designed the interiors with as much ornamentation as the external façade was devoid of. Patrons were greeted with ceilings adorned in plasterwork details, pilasters, capitals, friezes, and cartouches, signature elements of the Beaux-Arts style that Pflueger initially practised.

Several murals and frescoes adorned the ceilings and walls of the auditorium and the mezzanine floor, which brought an air of luxury to the theatre.[12] The auditorium’s tiered flooring and balcony seats provided every comfort necessary for watching a movie without obstruction in one’s line of vision. The Landmark designation report described the spaces as “richly toned” interior appointments, including a “gallery of mirrors” extending the height of the sidewalls, and “luxurious smoking rooms and cosmetic salons and other conveniences for modern patrons of fastidious temperament.”

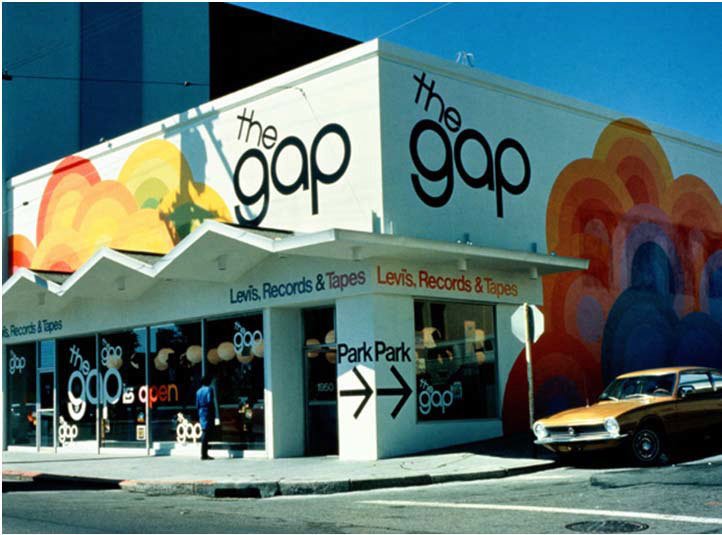

The store’s opening in the complex meant patronage from a younger demographic than what the El Rey had been used to, making its presence in the neighbourhood more far reaching. Comparably, the Lovebirds Studio, which opened its first store in 2022 in the 19th century Wesley Anglican Church in Mumbai’s Colaba area, may follow a similar trajectory. With its eccentric yet minimalistic clothing in a sea of boisterous fashion brands, it aims to catch customers’ eyes with diverse fashion senses.

In the same way that The Gap and El Rey were able to naturalise the past in everyday lives of San Franciscans, so might a fashion store coupled with a historical structure do the same in Mumbai. With very few adaptive reuse success stories in a city like Mumbai, the Lovebirds Studio, much like the Zara store near Flora Fountain in Fort, could, at least, serve as a prime example of façadism, which ensures the relevance of historic structures in a rapidly transforming city. It is not unreasonable to assume that the church may find greater visibility in the city.

Its Fall into ‘Grace’

The El Rey enjoyed its luxury status while it remained the only major theatre establishment in the neighbourhood, up until 1971. While improvements were periodically made to the state-of-the-art technology used in the single screen theatre, with the advent of the suburban-style, two-screen theatre models appearing in nearby districts, there was little else El Rey could do to meet the needs of its customers. Furthermore, during the 1960s and 70s, a period in America fraught with tension over several political churnings, including the American Civil Rights Movement, the surrounding neighbourhoods became home to more African-American families. Prevailing racial tensions, coupled with fear-mongering by exploitative real estate agents, led to ‘white flight’ in the early 1970s.[15] With the vicious cycle of investors pulling out, businesses closing, and the mere idea that crime-related activities would increase, the development of the neighbourhood stalled, and with it came the demise of El Rey as a ‘movie palace’. The last few years of the theatre were littered with its most insipid showings, with Jack Tillmany – the former owner of Gateway Cinema and a collector of theatre memorabilia in San Francisco – begrudgingly stating:“If the operators of the El Rey Theatre (United Artists Theatre Circuit) had simply planned to close the place down and walk away from it, it would have been a kinder gesture than what they did to it during its last few years of operation.” [16]

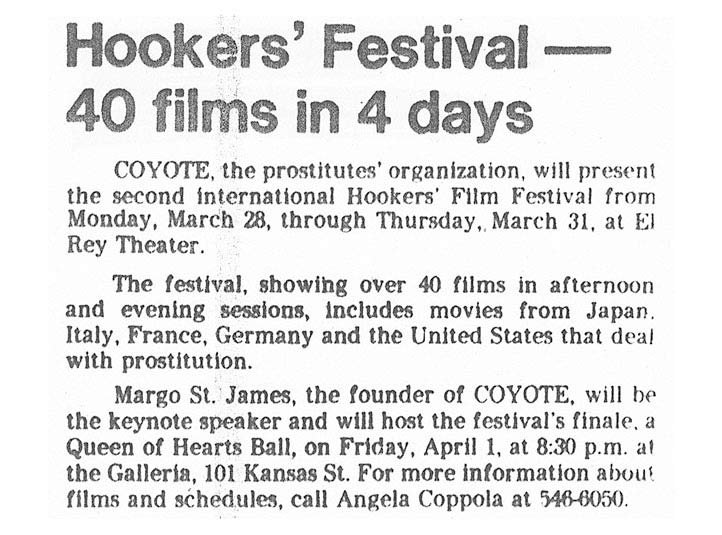

The final nail in the coffin was when on 29 March 1977, the theatre hosted the International Hookers Film Festival and ran a noon to midnight marathon of films like ‘Three Penny Opera’ (1931), and ‘Pandora’s Box’ (1929) – movies that were considered too racy to run in “respectable” establishments such as El Rey.

In a similarly bold move, Liberty cinema revamped its significance by hosting the KASHISH Mumbai International Queer Film Festival in 2014, which was originally organised in a 120-seater PVR in Juhu, since its inception in 2010.

This was a significant move as it came on the heels of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which criminalises same-sex relationships, being reinstated in the Indian Constitution by the Supreme Court, in 2013.[17] The move to the Liberty theatre brought renewed advocacy for the community and also opened the doors of the historic theatre to larger groups of people. The same could not be said for El Rey’s boldness, as it closed three days after the festival, on April 1, 1977, which seemed definitive at the time. After its unceremonious closing, El Rey enterprises sold the property to Voice of Pentecost, the evangelical Protestant church that occupied the building till 2015.[18]

By the time the mantle passed on to Gazowsky’s son, Richard, who renamed the church “A Place for Jesus”, the structure was in need of repairs. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, Richard took out a mortgage on the El Rey and implemented a series of alterations and upgrades to the church. However, it was the decision to finance his still unfinished science fiction film, called Gravity: The Shadow of Joseph, that effectively bankrupted the church, ultimately leading them to default on their payments.

This former beacon of luxury and beauty was sold in a foreclosure sale on November 25, 2015, to a joint group of developers.[21] However, several modifications had already been carried out while the theatre was in the church’s possession.

The renovation of the church was intended to solve the immediate need for a place of worship. But in doing so, the preservation of its Deco-influenced interiors and the ambiance they created were neglected. This is a practice seen closer home as well. The Royal Opera House in Bombay, for instance, was taken over by Ideal Pictures Ltd. in 1935, and completely renovated in the following year.

Landmark Designation

The spaces open to the public, such as the entrance lobby, auditorium, and bathrooms at the El Rey theatre, still retain a surprising degree of integrity in the featured Deco elements. A vast majority of the restorations and additions that were done to El Rey have been documented and recorded. The earliest alteration permission was given in 1956 to the then owners – United California Theatres – to replace the neon signage that was affixed to the tower.[24]In its prime, the tower sheltered a warning beacon for aeroplanes and a klieg light, drawing countless eyes to its astounding beauty. It has now emerged from relative obscurity to once again become the face of the revitalisation of the Ocean Avenue corridor.[25] While the Art Deco theatre had long been vying for landmark status, California law requires any religious community that occupies a historic building to agree to the landmark designation, which A Place for Jesus did not.[26]

The change of ownership in 2015 gave enthusiasts and historians alike the opportunity to revive a long-time dream to restore the erstwhile theatre as an icon of the neighbourhood, by serving as a community centre or a theatre. Inching ever so slowly towards a landmark status, it was unanimously approved, enabling federal and state tax incentives to be used to help restore the Art Deco masterpiece.

It was approved because its design met the standards set by the United States Department of the Interior (DOI), an organisation that prescribes rules and regulations for the protection of historic properties. It stipulated that the building itself should be preserved with care to prevent damage to the Art Deco features, and anything built on the property should adhere to a 40-foot height limit in conformity with the residential neighbourhood in the rear. Currently, the project has been stalled due to developers withdrawing their applications in August of 2019 due to financial complications, but hopes for this iconic structure are still alight in the neighbourhood. With any luck, the theatre will not be mothballed and will avoid perpetuating the cycle of neglect and irreparable changes it experienced for decades.

“The Beacon’s Rays Will Guide You”

Cinema has for long created common vocabularies and sensibilities that bind larger detached communities together, across geographies. The expansion of theatre outlets in a city can serve as a measure of a city’s growth. El Rey is an example of how an entire district has burgeoned and flourished under its shadow. One can draw comparisons with Aurora Talkies in Bombay, which was built in 1938 and was, as mentioned earlier, a neighbourhood theatre located right before the vast marshlands, way out in the then-suburbs of Matunga. The theatre followed the usual format of screening English movies popular at the time. However, if it was to survive antiquity and attract patrons, it needed to adjust to a neighbourhood that was experiencing an influx of South Indian residents, who filled the clerical and officer positions in industries and offices in Bombay, in the 1930s and 40s. The theatre screened Hindi, Marathi, Telugu, Tamil, and Malayalam films, which helped to keep the lights on in the cinema, whose main competitors were multiplexes. A changing cultural landscape forced Aurora Talkies to reinvent their brand and maintain their significance in line with the changing social demographic of the neighbourhood, which El Rey was not able to do for many reasons in San Francisco.

The concerted effort of many organisations and local communities helped bolster El Rey’s much needed restoration project. Having been designed from the beginning to exceed expectations, it can now be preserved in time. Both the Deepak (formerly Deepak Talkies) and Liberty Cinema in Mumbai have taken steps towards preservation, and on closer inspection, perhaps these steps can be replicated to transform El Rey too. A cinema theatre in Mumbai can be demolished under the Development Control Rules (DCR) but can only be replaced by another cinema theatre of the same capacity. Instead of being turned into a multiplex, the theatres have been restored and serve as alternative cinema venues. The Liberty Cinema has hosted stand-up comedy acts and music festivals, in addition to the KASHISH film festival.

What’s more, in 2018, having preserved a lot of its older motion picture paraphernalia, the Liberty was in the unique position to screen the 35 mm version of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, when the Hollywood auteur visited Mumbai for an event promoting the use and preservation of celluloid. The occasion drew young cinephiles and fans of the director who may have otherwise frequented chain theatres like PVR and INOX. Similarly, Deepak has reinvented itself into India’s first international film centre that hosts workshops and training programs for upcoming filmmakers.[28] It can be posited that the El Rey’s original spaces could still remain true to their cinematic roots and kickstart a wave of reviving lost, and encouraging new art forms in film.

In addition to bearing the face of the neighbourhood, El Rey is also a repository of history thanks to its multifaceted uses. Once again, it is poised to revive a neighbourhood that has wilted in recent years, though progress has been slow. Throughout its history, the El Rey Theatre has impacted change, but it has also been impacted by change. Architectural spaces have been known to transform into living organisms, reflecting the psychology of the people and responding to their needs, just as El Rey has done.

In the many facets of its life, one can see glimpses of several picture palaces and historic structures in Mumbai – some thriving, some holding on, and some that have succumbed to the rapidly transforming city. Across time zones and geographies, a theatre in a city by the waters tells a similar tale to one that is familiar closer home, in the island city of Mumbai.

As mobile screens and other forms of digital content consumption gain traction, traditional cinemas and theatres may find themselves competing for the attention of the viewer. But despite the plethora of new kinds of entertainment in the media landscape, the hope is that El Rey will keep its curtains open, with the possibility of obtaining a new lease on life.

Jessica Fernandes for Art Deco Mumbai

Jessica Fernandes is an architect based in Mumbai. She is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Architecture Design and History from Politecnico di Milano, Italy. Her interests lie in history, research and creating digital art.

* Bombay was officially renamed Mumbai in 1995. Wherever the article describes events before 1995, the city is referred to by its former name.