“…the Art Deco cinemas in Bombay underscore that there was more to going to the cinema than simply watching the pictures. Here a whole variety of consumptive activities intermingled, making these spaces dramatic and highly active locations.”

Michael Windover, ‘Exchanging looks : “Art Dekho” Movie Theatres in Bombay.’

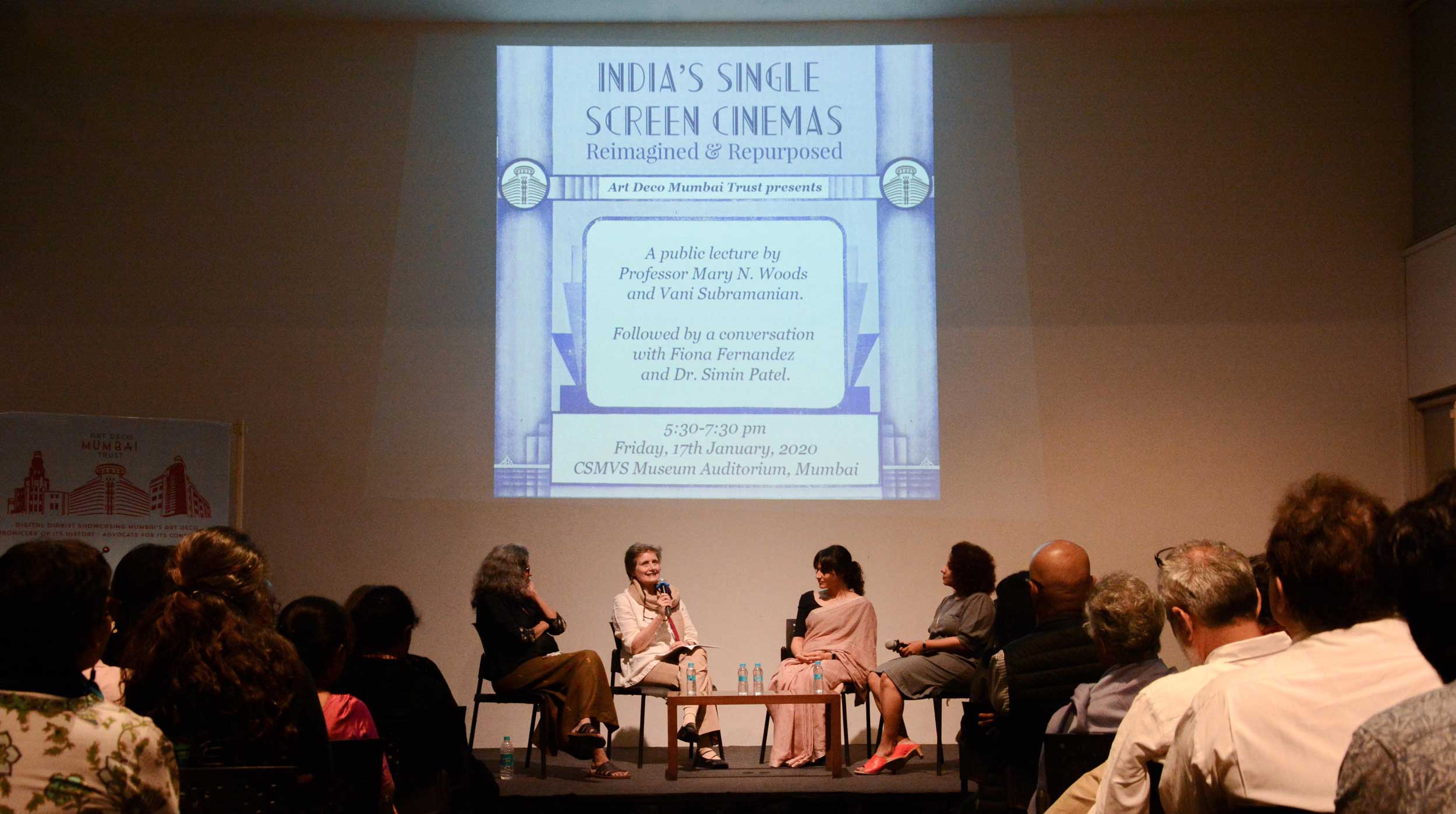

On 17th January, 2020, Art Deco Mumbai Trust hosted a public lecture by Professor Mary N. Woods and filmmaker Vani Subramanian at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai (formerly known as the Prince of Wales museum). The lecture was followed by a panel discussion with city historian Dr. Simin Patel, and Mid-Day Features Editor Ms. Fiona Fernandez.

Professor Mary N. Woods and Vani Subramanian highlighted the condition of the single screen cinemas in India. Although the Indian film industry is one of the biggest in the world, Art Deco single screen cinemas – described as ‘jewels woven in the urban fabric’- face losses, both financial and cultural, while multiplexes experience growth. The public lecture primarily focussed on the repurposing of single screen cinemas and the concept of cinema and migration in different facets of the urban landscape of Bombay (now Mumbai).

“Migrations were interlocked in complex ways and not in a linear way.”

Vani Subramanian, Filmmaker

Cinema is a migratory media; from the films to the cinema halls, architectural styles, materials used, the architects, the owners, labourers and the audiences, all were products of migration and contributed to the socio-cultural milieu of Bombay.

The status of Bombay as the mecca for migrants who dream of a better future is not a new one; rather, it began centuries ago. The cosmopolitan nature of the city is rooted in the varied histories of the migrant communities that began trickling in since the 1600s. Incentives such as the right to religious freedom (passed in 1677) and the lure of lucrative commercial prospects meant that there was a surge of migrants in the city, which significantly transformed the urban scenario of Bombay. Cinema as a medium has often been heralded as a reflection of current societal trends. In the case of Bombay, cinema spaces in its entirety, including the films, audiences, ambience and even the structure themselves, reflected the aspirations and the endless possibilities that the city offered. Several transformations were seen in the social and political life of Bombay alongside the evolution of theatres to cinemas – from the time of the creation of the Bombay Theatre in the 1770s, to the proliferation of cinema halls in the early 1900s. As Vani Subramanian opined, single screen Art Deco cinemas of the 1930s-50s inadvertently became a manifestation of the people’s aspirations, including a generation of architects inspired by western modernism, turning Bombay into a ‘cinema city.’

A hitherto unexplored topic was that of the cinema audiences comprising mainly of migrants. As mentioned previously, the island city of Bombay came into existence as a metropolis mainly due to the contribution of the migrant communities who began to arrive in earnest from the 17th century onwards. Migrants continue to play an important role in the urban landscape of the city, especially in the sphere of cinemas. Bombay witnessed a growth in the number of migrant workers from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in the 1990s – who constituted a major chunk of the audience – thus impacting the cinema industry in Bombay significantly. For example, there was an increase in the screening of Bhojpuri films during a time of crisis in the age of video parlours and pirated cds, in order to appeal to the large migrant audience. Cinemas offered a place for the ‘isolated urban nomads’ to form a sense of community, a home away from home, where they could find people from the same community, with similar languages and lifestyles, thereby reducing their loneliness and alienation in a new city.

“In those days when we were not bored with a lot of silly Russian and Czech films, a lot of George Raft films used to come to the Regal and Betty Grable to Eros. He was one of my favourites and I used to watch him sitting among the gods ( it cost four annas then and it was a long climb to the balcony).”

An excerpt from Temples of Desire by Busybee (Behram Contractor), published in the anthology Bombay, meri jaan edited by Jerry Pinto and Naresh Fernandes

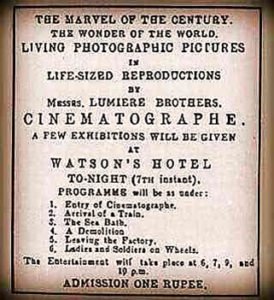

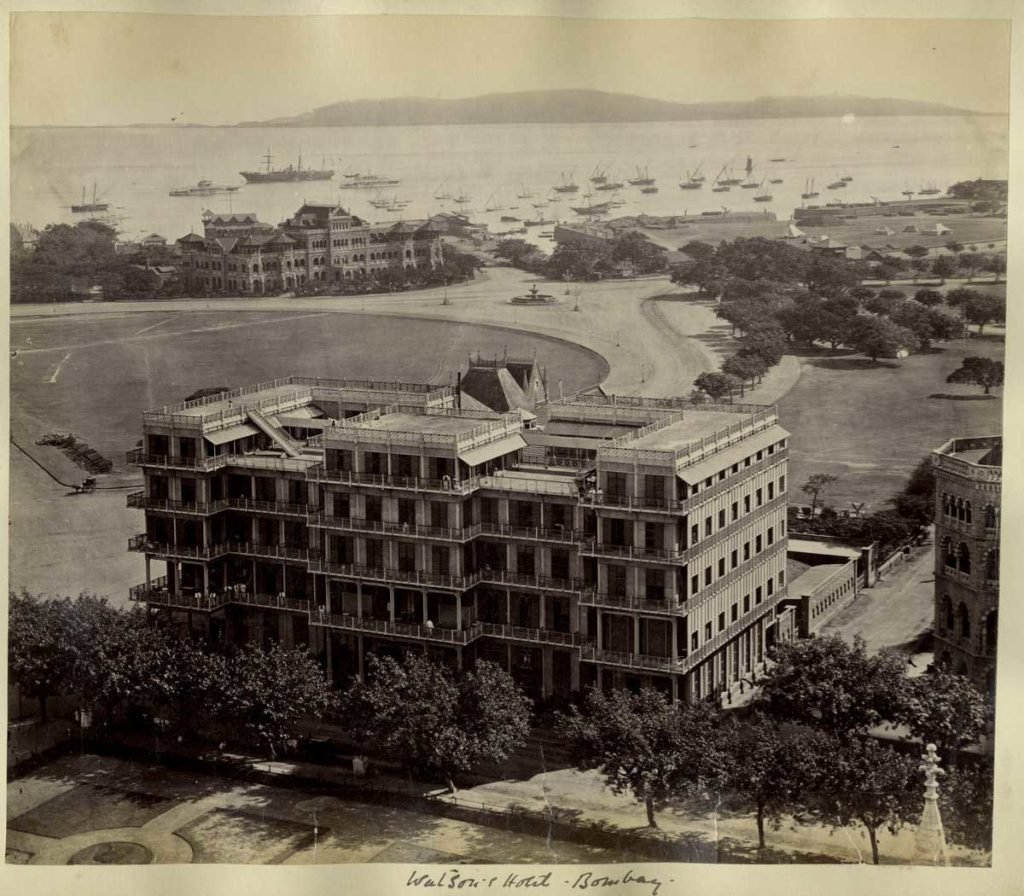

After the first ever movie screening in France, cinema travelled to Bombay (1896) where it was brought to the Watson’s Esplanade hotel for the European troops in Bombay. The Esplanade hotel itself was made of migratory materials; the structure had been prefabricated in Britain, shipped to Bombay and assembled on site. The advent of cinema led to the proliferation of cinema theatres in India.

Architecture played an important role in the process of cinema building. For example, the confluence of the local and global materials, technology, architect and the founder, led to the birth of Liberty theatre in Bombay. It had diversity in the materials used, as Indian marble, Burma teak, Canadian cedar, air conditioning from New York and a sound system from Germany were installed. It had a multi-use program; apart from its colossal 1200 seat theatre, it houses shops, offices, a penthouse and a preview theatre. It was exclusively showing Hindustani cinema when most theatres only showcased English movies. Liberty was born in 1947, a crucial time for India’s independence, and showing Hindi cinema gave a new identity to the theatre. Now cinema watching was for all.

The Liberty’s owner Nazir Hoosein’s grandfather, Mr. Hoosein Moolji, had migrated from Kutch to Bombay for better opportunities. Nazir’s father Habib Hoosein was a cinephile who was passionately building theatres which was later consolidated into one structure – the Liberty cinema.

“If Regal cinema, which opened in 1933, announced Art Deco’s gala entry into the city, Liberty in 1949, marked its grand finale.”

Dr. Simin Patel, City historian

Liberty is also an example of the repurposing and reimagining of cinemas – the late Mr. Nazir Hoosein envisioned that the Liberty be used as a space to host theatre performances, musical soirees, corporate events, film shoots and even exhibitions of Rolls Royces, old films (such as those featuring ‘Fearless Nadia’) and other vintage memorabilia. Sections of Liberty’s spaces were transformed and reused into stages and sit-in cafes; however, the original 1949 seats remained untouched.

Cinemas are now being repurposed as clinics, performance halls, theatre halls, exhibition centres etc. An interesting example of repurposing of cinemas was given by Delhi architect Sudeshna Chatterjee, who creates pop-up spaces for children of rag-pickers who beg around the cinemas, proving the multiplicity of possibilities for repurposing cinemas.

One of the main reasons for the decline of these once grandiose cinemas is the ever-evolving modes of viewing films. The advent of satellite television, cable network, streaming services and even pirated copies of films, changed the landscape of the cinema-going experience drastically. Previously, the idea of watching films by going to the cinema was almost like an event. Now it is more convenient, accessible, personalized, and yet detached, emphasizing on an individualistic experience rather than a community one.

“These single screen cinemas, like say, the threatened Udipis or the fast fading Hindu Lunch Homes, face an ever-looming threat from several factors, many of which are not even in their control, like real estate sharks, high rentals, redevelopment, and then, there is all-pervading impact of an unpredictable economy.”

Fiona Fernandez, BOMBAYNAMA, January 20, 2020 issue of ‘MiD-Day.’

The dilution of the original purpose of single screen cinemas was brought to the forefront with a unique analogy between a mall and a cinema hall. Cinema spaces, like malls, are designed strategically and exist as part of a larger economic structure. Both are constructed in a utilitarian way so that they remain sustainable. Buildings that housed single screen cinemas were (as mentioned before) constructed as multi-use spaces; it was not only a commercial space but also residential (the owners would often reside in the premises) and recreational (the cinemas were originally equipped with ballrooms and even an ice-skating rink in the case of the Eros cinema.) Cinema halls were equipped with food stalls or restaurants, parking lots, residential spaces and other properties which could be leased, hence increasing its overall viability; however, their main purpose was to screen films. A mall was similarly designed in such a way that the customers would be engaged in various commercial activities, other than that of visiting the anchor store or the main store which served as the primary source of revenue for the mall and was usually a popular retail store meant to attract people to visit the shopping complexes. If the main store (or the anchor store) failed, it led to the failure of the other stores in the mall. Similarly, the struggling business of screening films which was the primary function of single screen cinemas and their main source of revenue, decreased their viability which led to the fall of other informal economies that were in a symbiotic relationship with the cinemas halls.

The single screen theatres although designed for a singular purpose, led to the development of other activities around it and resulted in ‘cinema centers.’ As Dr. Simin Patel explained, Bombay had established a range of cinema centers from Sandhurst road and Lamington road formerly, to Grant road and Fort area later on. There was an informal hierarchy in the type of cinema halls, the visitors, the type of films shown and the neighborhoods in which these cinemas were located. There is a marked difference in the treatment of the more modest single screen Art Deco cinemas in Grant road and Byculla (such as the Central Plaza and Palace Talkies) and the grand structures of the Fort precinct (Eros, Regal, Liberty etc). While these cinemas are not as celebrated, the ornamentation in Palace Talkies and Central Plaza is on par with the ones in Fort.

“I’m fascinated by Prof. Woods and Vani for using migration as the tool to read between layers of the city, entertainment and identity, through a space-time continuum.”

Shubhika Malara, Communication and Design Practitioner

Professor Mary Woods and Vani Subramanian contribute a fresh perspective in the discourse on single screen cinemas, which steers away from the usual ubiquitous “nostalgic” route and explores subjects such as migration as an inherent component of the cinematic experience, especially in the city of Mumbai.

Despite the plethora of obstacles in the way of preserving the cultural heritage of India’s single screen cinemas, they have managed to survive, if only just. The example of a popular streaming website like Netflix helping to preserve Manhattan’s last surviving single screen theatre, The Paris Theatre, is an encouraging solution; ironic as it is that a form of digital media that has hastened the demise of single screen cinemas has also come to its aid. Efforts at the sustenance of these single screen cinemas include film restoration programmes and events hosted by organizations like the Film Heritage Foundation which are attended by royals, popular Bollywood stars etc. who patronize these single screen cinemas. Another way in which public awareness on the importance of these cinemas was raised was through the screening of Christopher Nolan’s ‘Interstellar’ in 35mm at Liberty cinema; Mumbai’s International LGBTQ film festival Kashish was held in Liberty as well, in tune with the ideas of tolerance and inclusivity that Mr. Nazir Hoosein had always advocated.

It behoves us to undertake conservation efforts in order to ensure that these cinemas function, not as ancient relics of the past or as properties under powerful lobbyists, but as active spaces of community interactions, enjoyment and aspirations that they were originally built for. Art Deco became an influential and iconic style in the sphere of cinema building in India and worldwide; it was malleable, modern and popular, as Mary Woods and Vani Subramanian explain, derived from the international style but localised as well, thus making it suitable for the masses at the time while embodying the adaptive and cosmopolitan nature of the city. While theorising the significance of Art Deco single screen cinemas as part of the tangible and intangible heritage of the city, a pertinent question was raised by an audience member during the panel session – were the cinemas influenced by the Art Deco style, or was the Art Deco style influenced by cinema theatres? – leaving the audience (as well as the panellists) much to ponder over.

Click here to view “Liberty Cinema: The Showplace of the Nation”, a short film by Art Deco Mumbai Trust.