In the 1920s, as the world was emerging from the losses of the First World War, a new design movement burst into view, taking the public imagination by storm. Retrospectively named “Art Deco” (after the French Arts Décoratifs), the style absorbed possibilities of the future presented by the brief economic prosperity of the interwar period. It embraced various design conventions and cultures, sometimes even leaning towards the fantastic to make a flamboyant splash through decorative motifs and patterns.

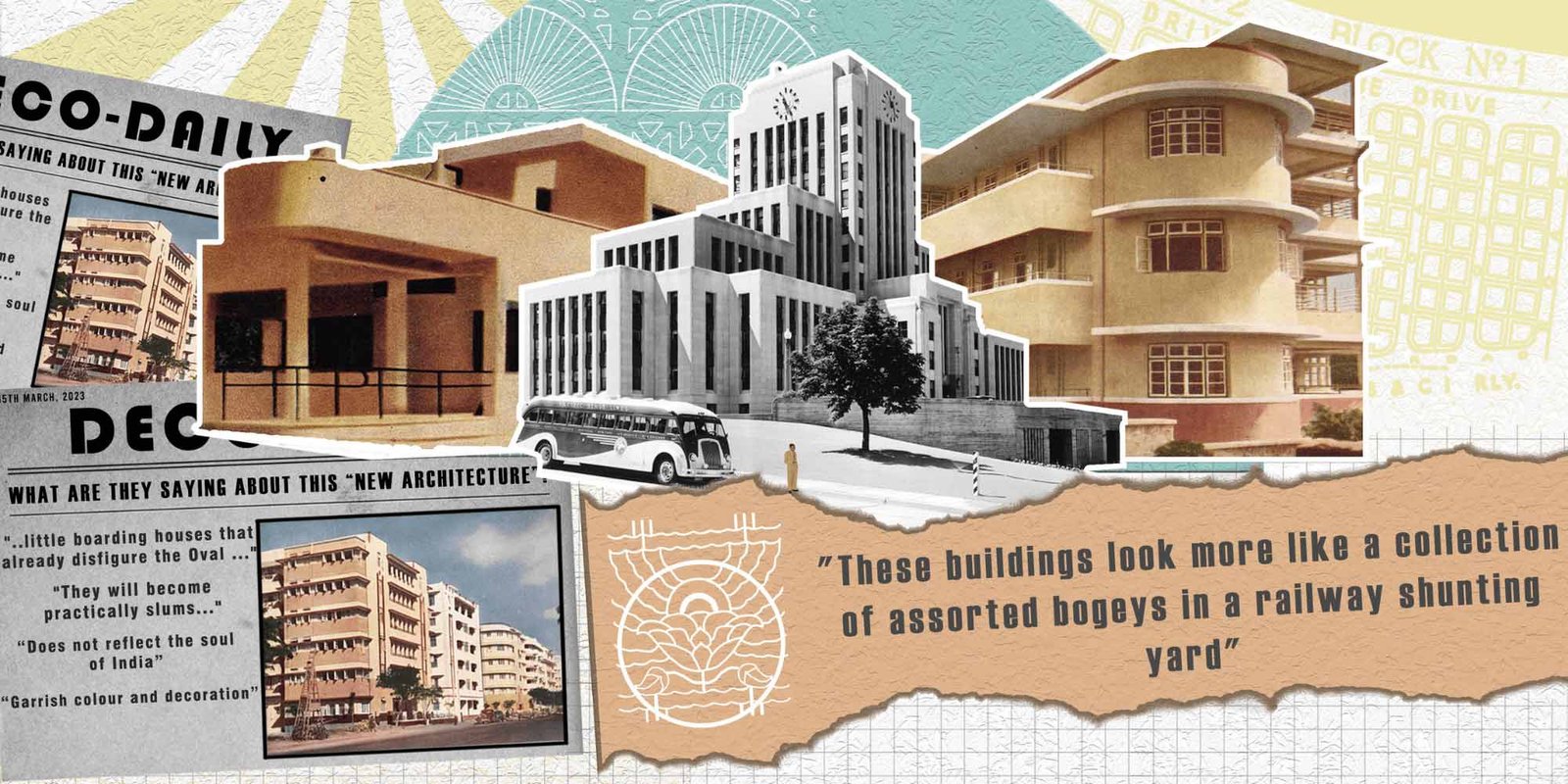

As is often the case with discourse around anything new, Art Deco was met with several opinions and points of view, many not necessarily favourable.

The slipperiness of its identity and its affinity to classic ornamentation (even as it identified itself as modern) prompted several criticisms. To the traditionalists, the style was too modern, to the radical modernists it was not modern enough. Some thought it was too ornamental, therefore hollow and without any theoretical underpinnings, while others accused it of being too stripped down.

It was this slipperiness, however, that extended into various interpretations, allowing it to be brought into the fold of jewellery design, furniture, fashion and more, beyond architecture and the built form.

Given the plethora of interpretations around this style or design movement, this essay is an attempt to put together various opinions, discourses and views around what we know today as Art Deco, at the time of its emergence as well as retrospectively.

While one of Art Deco Mumbai’s objectives has been dedicated to preserving and chronicling the history of the style in the city (and larger international contexts that influenced its spread in India), this essay takes a step back to assess the discourse around it more critically. In India, while it was adopted enthusiastically by the middle class, there is much to be said about how it was perceived vis-à-vis questions of class. Who could afford to live in the Art Deco apartments? How was the style interpreted in the backdrop of a raging nationalist movement? And where did it fit within the emerging canon of architectural discourse in India? In laying out these arguments, the attempt is not to come to Art Deco’s defence, as we are wont to do. It is an attempt to situate it within the wide range of debates it had engendered around the world, especially in India.

The Paris Exposition – A Defining Moment

Art Deco first emerged in France, at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris, in 1925. The six-month exhibition was organised by the French Government as a display of new ideas emerging in architecture, interior design, furniture, fashion, and more.

The exhibition was a roaring success, with pavilions set up by several other nations, mostly from Europe. The criteria for participation mandated that only new and original designs could be submitted – a complete breakaway from traditional and historical styles. Despite the mandate of “originality” at the fair, however, the abstracted classicism prevailing in these new designs was not lost on many, especially critics from the United States, the only Western nation conspicuously absent from the event. Voices within America, at the time, found the exhibition to simply be a self-serving exercise in promoting French decorative arts, rather than the beginning of a design movement that proliferated well into the 1940s and beyond.

Architect Le Corbusier, a foremost pioneer of modern architecture, was also at the Paris exposition, although his pavilion stood in stark contrast to the rest of the showcase.

Critical of the exposition’s (and French society’s) obsession with ostentatious objects to mark social hierarchies, Le Corbusier showcased a house for the ordinary “everyman” who emerged in the machine age – a functional, efficient and well-engineered “machine for living” that offered hygienic and healthy conditions beyond just style. [8]

His provocative pavilion was a direct acknowledgement of the prevailing housing crisis in France, in the face of which the extravagant motivations of the exposition seemed ill-considered.

It was only as Art Deco trickled out from this exhibition and spread to different parts of the world that it took on a popular form in its true sense, experimenting with more cost-friendly materials like plastic, often seen in household objects and modern appliances like the radio, and Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC), in the case of India’s built form.

This New Architecture – The India Context

Art Deco’s emergence in India, especially in Bombay, is a unique case study. While the style was still decorative in Bombay, it was vastly modest in scale when compared to the New York skyscrapers, and more so, in contrast to the imposing Victorian Gothic monuments commissioned by the British empire in the 19th century.

Largely residential in typology, it came up in Bombay through private commissions and gradually became the enduring choice for middle class housing across the city’s north-south axis.

But on domestic shores too, it did not go uncriticised, as it became the face of the vast land reclamations from the sea carried out since the 1920s. The orderly, grid-like urban planning of Oval Maidan and Marine Drive was a great way to decongest the old city, which was just emerging from the ravages of the Bubonic plague of 1896. The neatly laid out Art Deco apartment buildings in these new districts were built keeping in mind certain regulations, including uniform building heights, setbacks, high ceilings, balconies and windows that brought in fresh air from the sea. Like Le Corbusier’s plan for Paris, the idea was to create spacious structures that envisioned a more hygienic way of life, with greater per capita space, taking urban pressures away from the old city. It is, however, questionable how much these new apartment blocks solved the issue of overcrowding in the city. Art Deco became representative of an elite, upper middle class life, at least in its early debut in Bombay. In a 1936 address to the Rotary Club of Bombay, architect Claude Batley, then president of the Indian Institute of Architects (IIA), decried the development at the Oval Maidan as “little boarding houses that already disfigure the Oval.”[9] Much like Le Corbusier, to Batley’s mind, the decorative style – which he described simply as “new architecture” – did not adequately address the city’s housing crisis.

A style that “championed novelty without being radical”, it “dovetailed perfectly with capitalism’s remorseless expansion,” seamlessly integrating with the notion of a modern and advanced way of life, largely addressed to the city’s “Westernised elites,” Prakash notes. [12]

The criticism of Art Deco’s Western links is one that comes up often in Bombay. As the nationalist discourse gained force, Art Deco was simply not Indian enough for some. By 1954, Batley lamented the “inferiority complex” of “India’s youngest generation of architects” who, according to him, unquestioningly accepted the mandate of Western ideas, no matter how “hastily developed” or “inadequately tested” they were.[13] Modern Indian architecture should be developed on a solid base of its own traditions, he maintained.[14] Architect Sris Chandra Chatterjee, who helmed the ‘modern Indian architectural movement’, was particularly critical of Art Deco, which he referred to as the “ultra-modern style”. Chatterjee maintained Deco did not “reflect the soul of India” and was “destroying the creativity of architects”.[15][16] Interestingly, the urban development of modern Bombay as we know it today was as much an undertaking of Indian entrepreneurs as it was of the colonial state. As scholar of South Asian art and architecture, Preeti Chopra has argued, between the colonial government; Indian and European mercantile elites, engineers, architects and artists; Indian philanthropists, labourers and craftsmen, a “joint enterprise” acted in tandem to create the urban landscape of the city in the early 20th century.[17] Regardless of complex definitions of nationality at the time, clearly there were diverse parties negotiating what architectural style would best define a modern emerging India.

Bombay seems to have been practising its own form of international modernism long before India gained its independence. Despite the architecture of this period being regarded as “inferior or copied”, the city made the Art Deco style its own conduit to express emerging identities and aspirations that were significant to a local context. [18]

Fun, Frivolous and Fashionable

While several criticisms of the Art Deco style have alluded to its decorative aspects being its biggest flaw, the undercurrent seems to simply be the style’s association with having a good time (think excesses of the jazz age and ornate experiments with materials like glass and metal). A 1995 headline for a New York Times news report puts it succinctly: “Art Deco, still not forgiven for being fun”. [19] Whether in the United States, Europe or in Bombay, a preoccupation with aesthetics and style was regarded as an indulgence of frivolity, divorced from the rational, empirical inclinations of the modern period. “The evolution of culture comes to the same thing as the removal of ornaments from functional objects,” modernist architect Adolf Loos declared in his popular 1908 manifesto titled Ornament and Crime. [20] Likening the infatuation with ornament to an impulse of being “criminal or degenerate”, Loos maintained that being enamoured by frills was not befitting of “the man of our own times”. [21]Radicals or High Art Modernists saw Art Deco, at best, as “modernistic” as opposed to “modern”. Modern was a terminology reserved for designs based in scientific thought and with greater “theoretical underpinnings”.[22] Art Deco, on the other hand, was seemingly too consumed with style and not enough with ideology.

It had captured the fancy of the middle class, and in its popularity, often came to be associated with the low-brow. It could be perceived as joyous, playful and decorative, but seldom intellectual.

In Bombay, the decorative style became a great example of a new movement in design sensibility with the emergence of a novel material like RCC, which became a quick and cost-effective alternative to stone and timber. But even these pioneering concrete structures were seen as an “expression of vanity and affectation” by some of the leading architects and voices.[25]

To H. J. Billimoria, architect and honorary editor of the Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects, it embodied a “tendency to be vulgar”. “Curves and circles run into triangles, and triangles play havoc with straight lines, and when this is further heightened with amateurish colour schemes the result again ends in vulgarism,” he wrote of its decorative aspects in a 1938 issue of the journal. [26]

S. H. Parelkar, one-time president of the IIA who also designed Art Deco buildings in Bombay, took a more sympathetic view. He appreciated the emergence of new mechanical devices, materials and knowledge in the early 20th century, leading to a building boom. “There is discernible progress in it [“modernistic” architecture], and it is certainly not depraved as it is commonly supposed to be,” he wrote. But this architecture remained transitional and not yet modern even for Parelkar.[27] To K. H. Vakil, the style moderne made use of this transitional period in architecture, or the “vagaries” of the profession, to impose its “cleverly forced mannerisms”. [28] Speaking of its mid-air projections (concrete balconies without cantilevers), “garish colour and decoration”, Vakil posed the question:

“Is it constructivism, functionalism, or just the gay abandon in architectural vagaries conveniently accommodated under the serviceably elastic label – style moderne?”[29] This elasticity of definition cast several aspersions on the style, which constantly had to offer explanations for its supposed promiscuity.

Coming to the style’s defence, architect Steve Knight, President of the Art Deco Society of Washington, argues for a larger theme of synthesis despite the many influences it brings into its fold. “We do use the term Art Deco rather broadly to refer to contemporary architecture and design between the two World Wars, and this includes the highly ornamented Art Deco of the 1920s as well as the more pared down evolution of the 1930s.

“Unique characteristics tie Art Deco together, including geometricization, flattening, repetition, heightened use of color, and a romantic affinity for mechanization,” Knight states, adding that it is an “attitude as much as it is an artistic or stylistic movement”. [30]

It is ironic that this very Art Deco ensemble, which has variously been described as “a collection of assorted bogeys in a railway shunting yard” or as “biscuit tins”, is a recognised UNESCO World Heritage Site today, putting Bombay on the global map as a modern city. In fact, the UNESCO inscription recognises the Art Deco edifices (consisting of the precincts in Oval Maidan and Marine Drive, the very structures that were derided at the time of their construction) as a blend of “Indian design with Art Deco imagery” which lends itself to a unique style. Along with the Victorian Gothic ensemble, to which it has often been unfavourably compared, the Art Deco style is “testimony to the phases of modernization that Mumbai has undergone in the course of the 19th and 20th centuries.”[33]

In Conclusion

Art Deco in Bombay was the people’s style. It wasn’t codified, nor did it follow any state-defined mandate. It was commissioned, patronised and popularised by ordinary citizens largely because of its versatility, ease of construction, and the freedom it allowed to experiment with motifs, colours and designs, in addition to its climate-responsive possibilities.

It watered down the boundaries between high art and “low-brow” populist expressions, allowing flamboyant ideas from a Parisian fair to enter homes in Bombay and beyond. Much to the chagrin of the radical modernists, it turned symbols of modernity into decorative elements – like speed lines and porthole windows that represented modern voyage and aerodynamic innovations in this period.

While there is much said about who patronised the style, it equally caught the fancy of royalty who frequently travelled overseas, as well as middle class families living in modest housing in the suburbs of Matunga, Dadar or Sion. An aspirational style, it came to represent a shift from the vernacular and an arrival into the modern epoch. Whether modern or “modernistic”, it stood for a new vision of the city that laid emphasis on a better quality of life, hygienic living conditions and open spaces. The range of discourse it engendered confirmed that the style could not be circumscribed, but despite the many ways it has been described over the years, the one that remains constant is that it reflected the outlook of its inhabitants.[34] For young, modern families embracing Bombay as a new metropolis, the “old traditional family home” no longer remained the choice of habitation. The “modern flat-let” served as a self-sufficient home that did not require “an army of servants” to maintain.[35] In due course of time, as it happened, it took on a character of its local surroundings, responding to the prevailing climate, materials and the needs of its inhabitants.

As for ornamentation, Art Deco often looked beyond function although its designs were also embedded in scientific efficiency (streamlining, climate responsive elements like balconies and eyebrows, etc). In some sense, it broke the stringent binaries between pleasure and intellect, allowing its decorative elements to become an expression of identity, of its inhabitants, its surroundings and even the city at large. It may not be forgiven for being fun, but it seldom makes apologies for it.

* Bombay was officially renamed Mumbai in 1995. Wherever the article describes events before 1995, the city is referred to by its former name.

Digital illustration for header image by Neha Bhatt, for Art Deco Mumbai.

Suhasini Krishnan for Art Deco Mumbai

Suhasini is a writer and editor, with an academic background in Film Studies and History. Her research interests lie in cinema, modernity, and the making of an urban city.