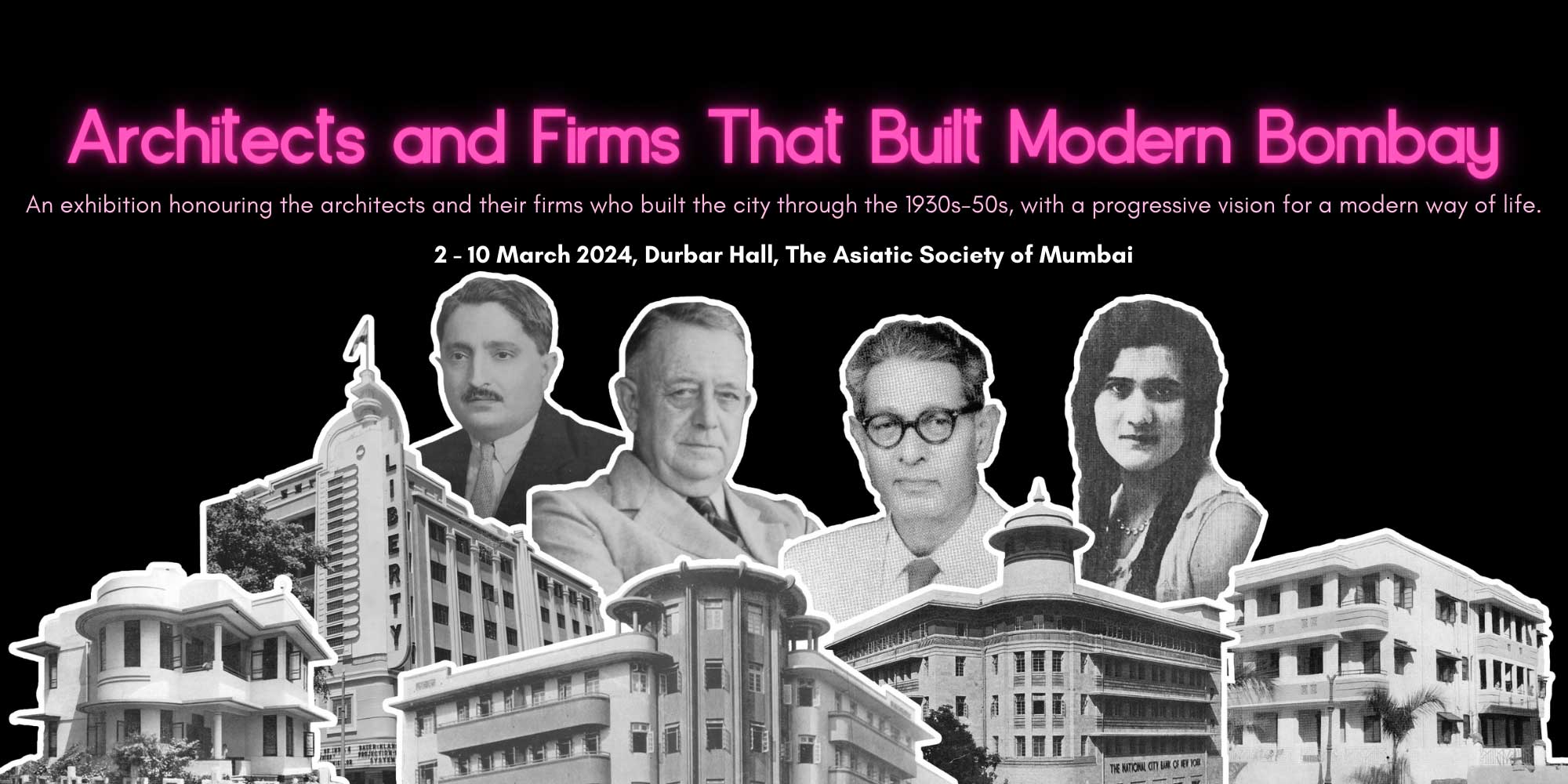

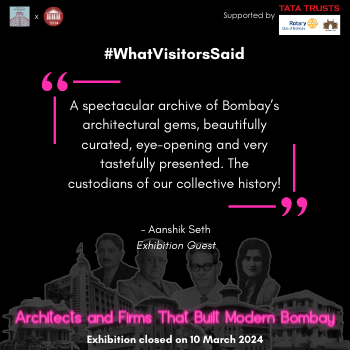

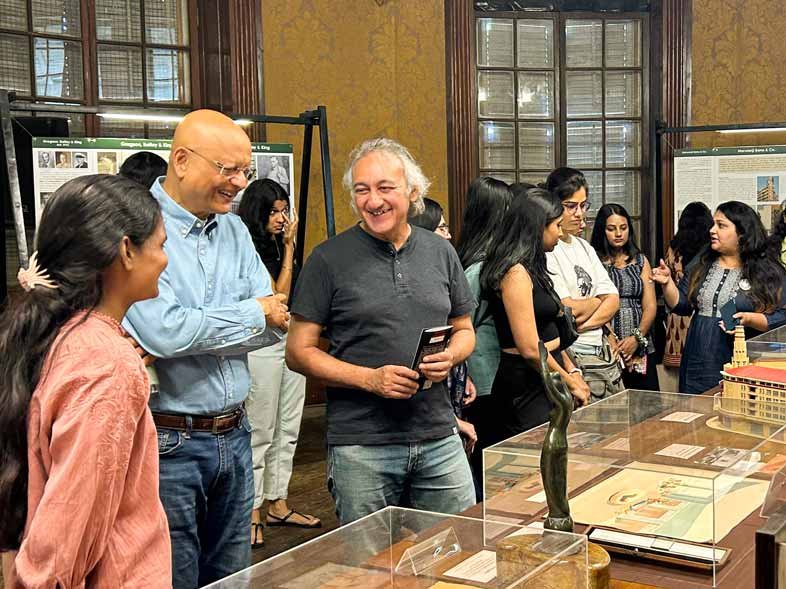

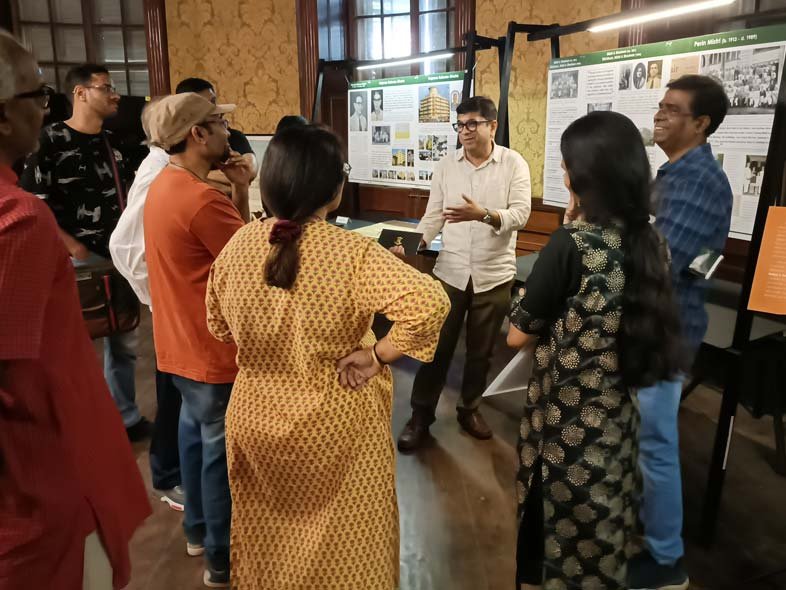

On Saturday, 2 March 2024, the exhibition ‘Architects and Firms That Built Modern Bombay’, opened at the Durbar Hall, the Asiatic Society of Mumbai, for a highly successful nine-day run. Presented by Art Deco Mumbai Trust and the Mumbai Research Centre of the Asiatic Society of Mumbai, and supported by TATA Trusts and the Rotary Club of Bombay, this exhibition was a tribute to the people that shaped the city, largely in the Art Deco style, through the 1930s-50s. Their works covered large swathes of Bombay, shaping the city as we know it. Yet they are seldom acknowledged.

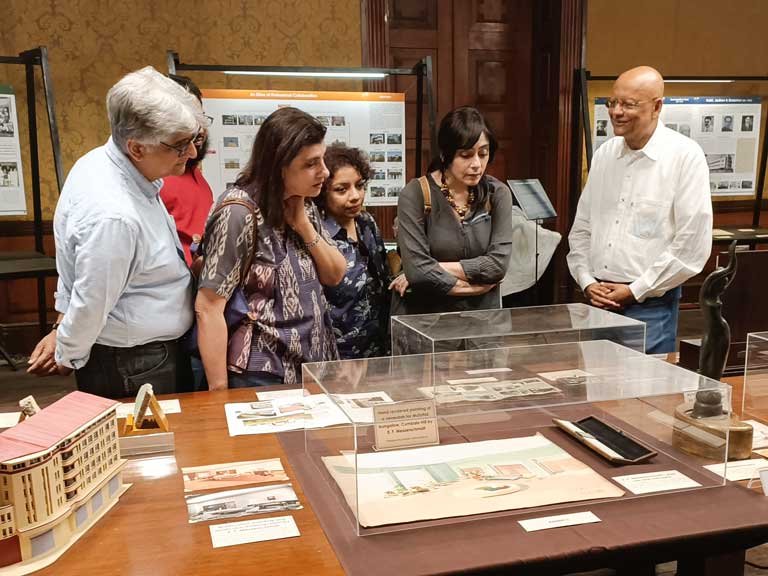

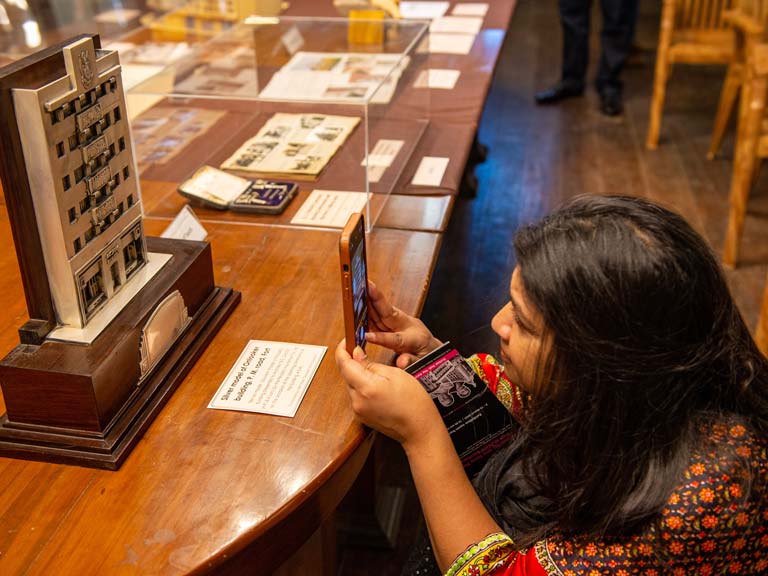

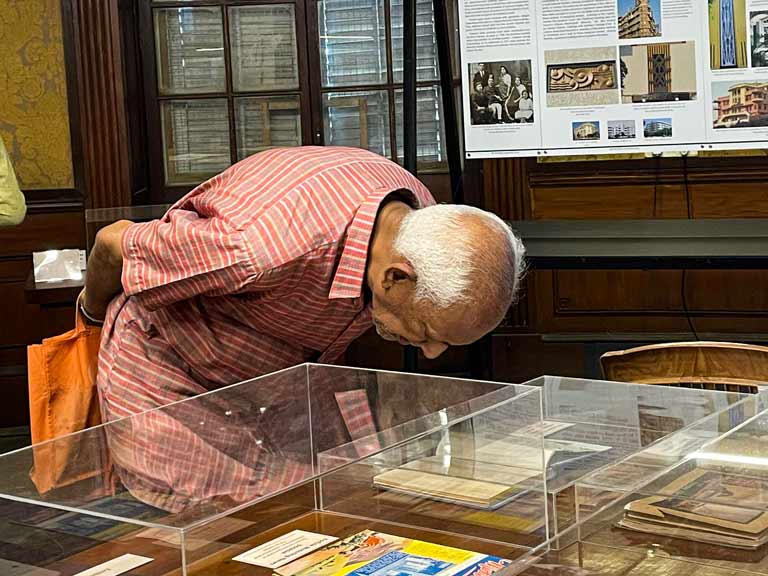

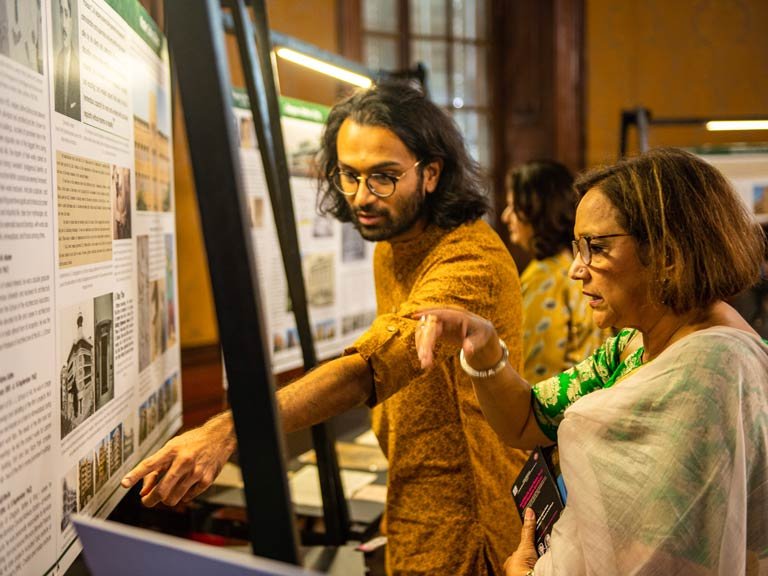

Through stories that brought to the surface the people behind the city’s built form, along with rare personal memorabilia from their family archives, the exhibition generated a forum that allowed people to engage with their city. It presented an opportunity to learn more about its history and ways of living, and perhaps even contemplate the choices they wish to make for its future. It brought to light a history of the city and its people that is seldom spoken of, but which Bombay continues to enjoy to date.

Below are extracts and glimpses from the exhibition.

Curatorial Note by Art Deco Mumbai

With the turn of the 20th century, as the world emerged from the losses of the First World War, a new design and aesthetic movement burst into view. Retrospectively called “Art Deco”, it was crystallised in Paris at the 1925 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts). Bombay at the time, a thriving port city, was also coming into its own. As architects and artists experimented with design and new materials, a dream for a new city was being visualised, in a country moving fast towards independence from colonial rule.

In this milieu emerged the early seeds of a modern architectural practice in India. Several architects and firms that were active at this time were first-generation Indian architects, graduating from homegrown schools like Sir J. J. School of Art, Bombay. The Back Bay Reclamations of the 1920s created vast new lands to develop, and these architects built much of the city, largely in the Art Deco style, using a new construction material called Reinforced Concrete Cement (RCC). Their works created whole new neighbourhoods, and cut across typologies – schools, hospitals, hotels, cinema theatres, bungalows, and a newly emerging residential unit, apartments. These were planned neighbourhoods, expanding within the ambit of progressive building codes set by the Public Works Department and the Bombay City Improvement Trust.

In many ways, the essence of Bombay’s early cosmopolitanism lies in how these neighbourhoods were designed. Yet, they are seldom recognised for their singular contribution in shaping modern Bombay. The creators of iconic monuments – like the Victoria Terminus (Frederick William Stevens); the Prince of Wales Museum and Gateway of India (George Wittet); the Bombay High Court (Col. James A. Fuller) are widely celebrated. As significant as they were, this exhibition is an attempt to transition the narrative from the masters of Neo-Gothic and Indo-Saracenic, and bring attention to architects who eventually had a wider footprint on the city.

They were peers who enjoyed a spirit of discourse. Several pages of the Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects (a body formed in 1929) comprised vibrant exchanges between these professionals – debating the vision of India’s emerging modernity, and architecture for the everyday man. They merged modernity with prevalent cultural and stylistic practices that reflected swadeshi sensibilities, using a unique stylisation of Art Deco adapted to Bombay. This exhibition hopes to make accessible records and information on these architects, the buildings they designed, their professional collaborations, and other details. It is based on the last 7 years of work undertaken by the Art Deco Mumbai Trust, building a repository of information from archival journals, newspapers, oral histories, books, photo documentation, and more. It also comprises sources from the Indian Institute of Architects, The British Library, Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), among others.

There are, of course, lacunae that must be acknowledged. The buildings identified are based on Art Deco Mumbai’s photo documentation practice, which is an ongoing process. Although we see a few modest housing schemes in the Deco style emerge in the suburbs, it may also be argued that affordable housing, a larger systemic concern, remained inadequately addressed by official bodies. Ultimately, these buildings were enjoyed by the middle classes, while the working classes, relegated to overloaded chawls, remained there. Yet these architects were responsible for much of the city’s formations from the 1930s to the 50s, introducing style, innovation and aspirations for modern, comfortable ways of living into its built form. From Bombay to Mumbai, these works continue to form the popular imagination of the city, and the people of this metropolis still live and work in these buildings. Their practices and vision became conduits to express a nascent but strong Indian identity, in its various versions and manifestations.

For this, they must be acknowledged. This exhibition is a tribute to them.

Afterword by Mustansir Dalvi, PhD

The 1930s and 40s were a unique period in Bombay’s architectural history, a golden period almost, where so many practices produced a large number of buildings of amazing consistency. All the architects and firms you have just seen formed the first cohort of Bombay architects. Whether born in the city or elsewhere, they all designed on well laid out plots, small or large, in the many planning schemes of the City Improvement Trust, on reclamations to the south and to the north of the mill lands. Together, they gave a new discernable and appealing appearance to the city.

While these were a diverse group of architects, each with their own preferences and penchants, they still contributed to a singular vision of creating a coherent urban fabric. In most cases, they shared a common background, either as teachers or students of the Architecture Department of the Sir J. J. School of Arts, the only architecture school in the country at the time. Their common vision extended to the practices these graduating architects soon set up. In fact, so much was the synergy between academia and the profession, that the principals of the largest architectural firms in Bombay – Claude Batley (of Gregson, Batley & King) and Chimanlal M. Master (of Master, Sathe & Bhuta) – were the heads of the school from the 1920s to the 1940s. Students were encouraged to attend school in the morning and work at these same offices in the afternoon. The setting up and functioning of the Indian Institute of Architects in 1929 (which had its origins in the Architectural Student’s Association in the Sir J.J. School in 1917), acted as a fulcrum for practice, discussion, argument and bonhomie.

In his city memoir ‘Boombay: from Precincts to Sprawl’, architect Kamu Iyer succinctly describes how the bye-laws at the time led to the formal character of the city: “The Improvement Trust had a vision of how a planned settlement should look. Layouts, planning and building rules were intended to create a coherent urban fabric… architects had to submit for approval the building along with the details of the entrance (elevations)… approvals always came only after a discussion with the Chief Architect of the Improvement Trust.” This shows how invested even the approving bodies were in creating a contemporary urbanity through a practice rooted in collegiality.

Iyer further says: “The Trust did not insist on uniform facades, and the buildings in these layouts differed from one another in external appearance. However they coalesced into one harmonious visual entity because they were not designed to be iconic, stand-alone buildings.” While building codes may have shaped their designs, every architect found a place in the sun through individual expression. No two Art Deco facades are the same, but they all display, to use Wittgenstein’s famous term, ‘family resemblances’. Self similarity was the cornerstone of a commonality of practice.

Ultimately, we must acknowledge the impact these architects, through their designs, had on the citizens of Bombay. This architecture was embraced by its users from its very inception, and continues to be validated through constant use, now for 80 or 90 years. In their aspect, these buildings were presented full-frontally to the public realm, so the person on the street could directly appreciate and interact with them. The architects whose work you have seen in this exhibition, and their colleagues and associates, individually and severally, helped to build the Bombay that we today, in 2024, can still take for granted.

Architects and Firms That Built Modern Bombay, 2-10 March 2024.