Introduction

In Mumbai, a city largely characterised today by its vertical expansion and glass towers, Art Deco buildings were once deemed as the first ‘high rises’. Bombay was a thriving metropolis, and city building regulations catered to its perpetually rising population. In the 1940s, even as the Art Deco style had just emerged, there was demand from building owners for permission to construct extra floors above existing buildings of various architectural styles. This move would accommodate more residents within the same premises. Eventually, owners of the new Art Deco buildings also succumbed to the profitability of this idea, and expressed their desire to expand vertically.

Concessions in building regulations allowed such additional floors. This trend commenced in 1948, only a decade after the development of Oval Maidan and Marine Drive, the iconic Art Deco precincts on the Backbay Reclamation, gaining further momentum with the 1967 Development Plan (DP) for Bombay. This Plan introduced the concept of ‘Floor Space Index’ or FSI – a tool designed to control the density of a demarcated neighbourhood based on a single formula.

Marine Drive and Oval Maidan were designed with ample frontage and public open space, allowing pedestrians a complete view. For the citizens of Mumbai, irrespective of their age group, the experience of the defined visual skyline is part of the high associational value of these neighbourhoods, along with several memories associated with the public space. However, the additions over time were designed differently from the parent building and varied in scale and height. These additions, while addressing the city’s growing spatial needs, introduced several conflicting elements to the once uniform skyline, also leading to the loss of some distinctive Art Deco features. It created a heterogeneous skyline, impacting the original aesthetic of these structures.

This essay explores the nature, design and extent of these additions, with a focus on the precincts of the Backbay Reclamation, viz. Marine Drive and Oval Maidan, with a few examples from Shivaji Park, Dadar.

The process of adding more floors has been driven by a complex interplay of regulatory frameworks, economic incentives, urban density and public demand. The impact of these additions on the broader context of the property, the precinct and the city have also been analysed.

Municipal Regulations for Building Heights and Addition of Floors

Urban policies and regulations are not only responsible for the aesthetics of neighbourhoods, but also for its density and the living standards it offers to people. Government bodies made efforts to adapt to the changing needs of the city by enabling certain provisions in law or amending existing ones. Over a century, however, a multitude of arbitrary regulations have caused modifications in buildings that are irreversible, which ultimately changed the way these localities are experienced today.

Regulations before Art Deco

Barring a few specific commercial localities, Art Deco neighbourhoods are mostly residential. Before the advent of apartment buildings, facilitated largely by the Art Deco style, the city’s population lived in building typologies like gaothans, chawls, or other forms of load-bearing buildings built using brick and stone. The Bombay Municipal Corporation Act of 1888 was the fundamental regulatory framework followed by the city at the time, which had regulations designed with load-bearing buildings in consideration.

The Bubonic plague of 1896, and the consequent loss of lives, prompted the creation of the Bombay City Improvement Trust (BIT) in 1898. In 1905, a small addition was made to the Municipal Act of 1888. This rule capped buildings in the city to a maximum height of 70 ft or 21.3 metres, measured from the street height outside the building. Given that all the buildings in the city around 1905 had load-bearing structural systems, the prescribed maximum height was also a practical limitation. The BIT then suggested policies to improve hygiene and living conditions in the city by prioritising light and ventilation in the built form.

In 1912, a “63.5 degree Light and Air Plane Law” was discussed in the second All India Sanitary Conference held in Madras.[1] This angle dictated the maximum height of a building and the minimum open space to be left as a setback behind the compound wall, as illustrated in Figure 1. Two angles of 63.5 degree could be drawn from the nearest built structure, to derive the maximum height of this building. After extensive debate and discussion, the rule was finally implemented in 1919. [2]

Concessions in Municipal Regulations from 1948

Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC), introduced in India in the 1930s as a structural material, quickly materialised as a legitimate construction method for newer developments, notably for Bombay’s planned neighbourhoods in the Art Deco style.

Concrete had immense potential; it was neither dominantly linear like timber, nor heavy and solid like stone. The fluidity of the material and its ability to mould itself into any imagined form opened creative doors. It allowed building heights that were hitherto unheard of, although they were compelled to stay under the maximum height stipulation of 70 ft.[3] For ensuring light and ventilation, the 63.5 degree angle rule was followed.

While it is widely believed that floors were added to many heritage buildings after ‘FSI’ or Floor Space Index was mandated in 1967, there is evidence of this beginning much earlier.

Also known as Floor Area Ratio, FSI is the ratio of the total area of the building on all floors and the gross plot area. The built-up area (BUA) is calculated with simple geometric methods, and deductions are made for certain spaces stipulated in local regulations.[11] The DP of 1967 further facilitated the practice of adding floors to existing buildings. Every locality in Bombay was designated a specific permissible FSI. Building owners could conveniently add extra floors above the building, provided the permissible FSI was higher than the consumed FSI of the building.

Types of Floor Additions Over Time

As a result of concessions in building regulations, a variety of additions in terms of scale and design are now seen on various buildings, Art Deco or not.

Additional Floors That Maintain Plan Profiles

In certain buildings, the added floor is built precisely above the building line of the lower floors to retain the plan profile and building dimensions. In the Indian Merchants Chamber (Figure 3 below), the added floor ends below the roof of the central turret. The floor is easy to distinguish as a later addition; however, it blends with the building line, making it less obvious to passers-by. In Ram Mahal (Figure 4 below), the added floor follows the precise curves of the floor below; the difference is only seen in the windows of the added floor. In Green Fields (Figure 5 below), the sixth floor rises to the level of the crown detail with flutings, and a corner window is replicated, blending the addition with the original building.

Confused Ascents: Haphazard Additional Floors

Firuz Ara (Figure 6 below) is a corner building at the junction of Madam Cama Road and Maharshi Karve Road, opposite Moonlight Building at the southern end of Oval Maidan. Two storeys have been added to this building in a haphazard fashion, without consideration for the architectural design or style. Firdaus (Figure 7 below) on Marine Drive stands out due to its addition of a pitched-roof penthouse. No other building on the seafront had such a roof, the uniform flat roof being the norm – a testament to complete disregard for the city’s skyline while constructing an additional storey.

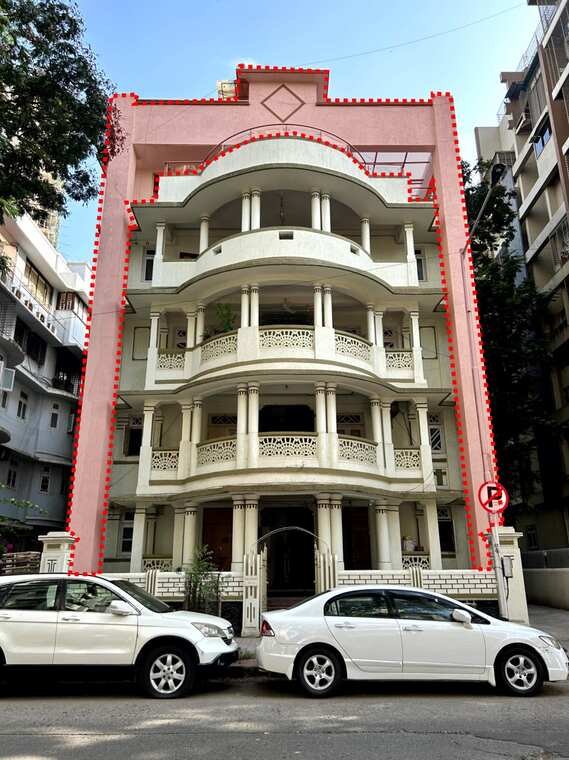

Building a Building on a Building

The much-debated method of extending the building height came without any structural baggage. This was particularly popular in the low-rise precincts of Dadar and Matunga. The foundations of the new constructions were cast within the space around the building, and heavy columns carried the weight of a second alien building, built around the same structure. Figures 8 and 9 illustrate two examples in Shivaji Park, Dadar, where the add-on building has been done relatively sensitively, and can be distinguished from the older construction.

However, there are several other haphazard examples in the central suburbs where an Art Deco building surely lies hidden behind heavy pillars of the ‘other’ building. The building entities often have connected services in the form of staircases, lobbies, lifts, plumbing, and drainage lines, even though the building, in essence, is separate.

Some say it is the solution to our housing problems, while others consider it an eyesore.

Homogeneous Buildings Interrupted: Giri Kunj, Bharatiya Bhavan, Hem Prabha

Starting at Seksaria Building, a consecutive stretch of eight similar buildings along the central part of the Marine Drive Precinct continues up to Sonawala Building (as seen in figure 10). They were designed by the prominent architectural firm Master, Sathe & Bhuta. These buildings were designed with a similar plot size, setbacks, massing and a uniform original building height of G+5 – following all guidelines stipulated for the Backbay Reclamation.

Along this historically significant stretch, there are three examples of floor additions made to buildings of the same size, yet these additions differ greatly in their aesthetic sensitivity. Giri Kunj (Figure 11) is a G+5 building with two added floors following the same profile, and designed with circular balconies identical to the floors below. The balconies in the middle of the sixth and seventh storey are the only portions of the floor protruding oddly.

Bharatiya Bhavan (Figure 12), has a sixth and seventh floor addition that follows a rectangular plan above the same building profile, but the corner balconies have been left out. While inauthentic to the original design, this also makes the addition easily distinguishable.

The extra floors in Hem Prabha (Figure 13) have neither followed the wall profiles of the floor below, nor maintained the floor area. The floors here recede from the side facades of the original floors.

In the process, various decorative elements were also demolished from the last floor or terrace of these buildings, such as the rectangular canopies atop Giri Kunj and Hemprabha seen in Figure 10, and bandings on the parapet wall of Bharatiya Bhavan. These buildings, although cohesive in their original form, now appear incongruous with one another and degrade the planned massing of Marine Drive.

Material Limitations

Several insurance company buildings in the late 1930s used stone cladding on their facades, with beautifully carved embellishments. The material blended well with the 19th century buildings in the Fort area. Industrial Assurance Building (Figure 14) on Veer Nariman Road is a fine example of a building with Malad stone cladding.[12] The added floor did not follow the material palette of the original building.

In the latter half of the 20th century, stone as a material, became expensive, irrelevant, and redundant. This floor was thus plastered and painted.

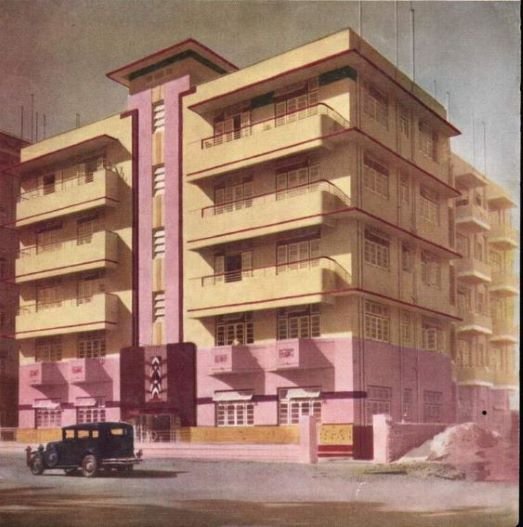

Hybridised Additions: Homogenous yet Unrecognisable

Court View, Oval Maidan was originally a Ground + 4 storeyed building (as seen in the archival image in Figure 15), unlike many others in the area. The later floor addition took into account the balcony design of the original building, as well as the stairwell windows. A fifth central window was not only recreated as per the original, but the ventilators above the stairwell were also retained and placed above the new construction. Barring the size of the flat roof of the staircase headroom, it is difficult to identify any difference between the archival image and the recent image of the building (Figure 16). The building design was replicated, and its decorative features were retained. The floor addition in Court View is thus an example of a sensitive addition which respects the original construction.

Interestingly, there are International Charters that do not recommend this. The Burra Charter of 2013 [13] is a document used by many countries as a manual for heritage conservation. It mentions that additions to a heritage structure are acceptable when they do not mislead the existing interpretation of the building. It also recommends that new additions should be easily distinguishable, and imitation is not ideal. For Court View, one can argue that as per the commonly accepted international standards, the additional floor, by virtue of being unrecognisable as an addition, lowers the authenticity or heritage value of the building. However, the Charters are simply a guideline and may be interpreted differently for various building typologies.

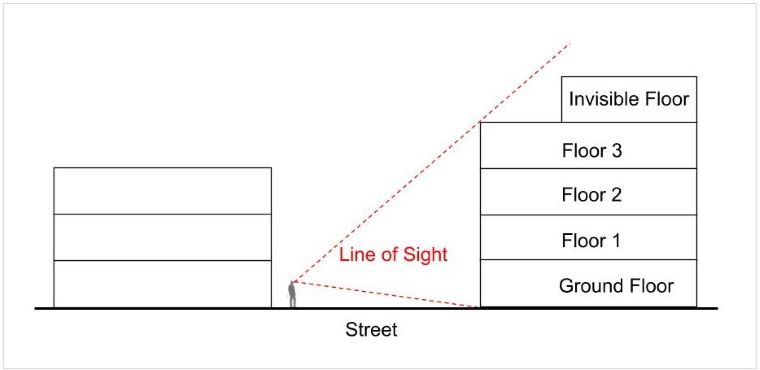

Invisible Floors

Buildings on small and narrow streets can benefit from the advantage of hiding the addition of a partial floor. This partial floor does not cover the entire building line. It can be constructed in the rear half of the building. Figure 17 illustrates the last floor that recedes from the front of the building, but stays hidden from the ‘line of sight’, behind the third floor. Very few buildings in the city have been able to use this line of sight from the street efficiently enough to add an invisible floor. Desai Cottage in Shivaji Park (now demolished), seen in Figures 18 and 19, was one such example located on a narrow road in the locality, allowing the line of vision to conceal the addition of a floor.

The Impact of Transition – Loss of Authenticity

Art Deco as a style was prominent only until the early 1950s. The plots had lease terms that stipulated that building construction must be completed within two years of land allotment.[14] As a result, planned neighbourhoods that were designed for residential purposes were developed all at once, in a span of two years. However, the timeline of the additions is not uniform. It spans a period from 1948 until the 1970s.

The parent style was compromised when these additions were made. The newer floors were visualised as a purely functional requirement, rather than a well-designed extension of the Art Deco building.

Empress Court, a prominent street corner facing building opposite Oval Maidan, was originally a G+5 structure (as seen in the archival image in Figure 20). The additional sixth floor follows the original building lines, but has a different design in the central portion. Two nautical inspired canopies on the original terrace were lost in the process of this floor addition.

In lieu of these floor additions, decorative elements on the last floors of several Art Deco buildings were hidden or demolished. Such elements were exclusive not only to the style but also to the respective building. They were not removed and set aside safely to be restored later, nor were there guidelines by the Municipal Corporation that would ensure the preservation of architectural integrity.

Moreover, some owners with financial constraints could not add floors to their buildings due to a significant construction cost. A variety of limiting factors influenced the feasibility of adding floors. However, what it resulted in was an uneven pattern of floor additions which altered the city’s skyline.

The Impact of FSI – A Constant with Variables

The FSI legislation has also resulted in a compromised skyline. According to the 1967 DP, plots of Art Deco buildings along Oval Maidan and Marine Drive were granted an FSI of 2.45 (see Figure 2 for sample FSI calculation). However, buildings that appear similar on the outside could be drastically different on the inside. The consumed FSI of adjacent buildings could also differ greatly, depending on the area of their courtyard or staircase, which could be deducted. After these calculations, the permissible constant would dictate if an additional floor was allowed for this building.

On Marine Drive, the buildings with G+5 floors had a consumed FSI of approximately 2.1 (calculated for Bharatiya Bhavan in Figure 13). The maximum permissible FSI in 1967 of 2.45, enabled Bharatiya Bhavan to add two additional floors, as did similar-sized buildings in the line. For Fairlawn at Oval Maidan, the consumed floor space index calculation for G+5 floors would have been 3.0, which exceeded the permissible FSI of 2.45, possibly limiting the addition of a floor.

Meanwhile, three buildings away, Green Fields at Oval Maidan, with a similar initial consumed FSI of 3, had a floor added in 1965 based on single-building permission, before the Development Plan and the FSI ruling were formalised. Corner plots along the same stretch, like Empress Court (Figure 21), have much larger plot sizes, which would have derived a different consumed FSI and enabled the addition of a floor.

Contrary to the original Backbay Reclamation Regulations of the 1930s, which limited heights for uniformity, FSI only controlled the density of precincts. It was a single number that introduced new variables that determined the feasibility of additional floors.

In Conclusion – The Larger Consequences

While the addition of a floor or two to buildings in Mumbai may not appear drastic, over time it has compromised the aesthetic value of the precinct and changed the experience of the uniform skyline of the original design. This pattern emerged in most of the planned neighbourhoods that were developed in the first half of the 20th century.

Even minor alterations and additions have implications for the integrity of the building, not only aesthetically but also structurally. The original design of the planned neighbourhoods of the early 20th century was responsive to climate; however, the additions have not been well thought out. The additional floor often skipped balconies in a bid to make construction economical. This was peculiar, particularly for the last floor, which would be heavily exposed to the environment. Balconies are instrumental in preventing rainwater-related leakage, and their elimination has resulted in several issues for top-floor residents. Lack of maintenance of these buildings has further amplified the threats to their stability and integrity.

As has been evident through the examples above, even minor policy changes can affect and degrade living standards. For example, while the 1991 DP [16] allowed balconies to be excluded from the calculation of FSI, the updated regulations in 2012 [17]mandated them to be included. This was reiterated in the Development Plan of 2034.[18]

A simple play of ‘calculations’ and ‘deductions’ now means that balconies have been deducted from our future.

With added floors, the buildings in The Victorian Gothic and Art Deco Ensembles of Mumbai, which was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 2018, were not entirely authentic. Yet, this group of buildings was considered to be collectively intact in their building plan, setbacks, corner articulations, and massing with a strong visual integrity. The original features were described as ‘mostly intact despite minor alterations’.[19] The inscribed site displays various time periods in the development of Bombay, with all its layers, manifesting in the form of architectural styles and technological development. The combined historical and architectural value of the precinct seems to have overshadowed the minor additions and subtractions in the buildings. This signifies the importance of several other Art Deco neighbourhoods in the city, that are also precincts worth preserving. After all, well-lived buildings must also be well loved!

Varada Phadkay for Art Deco Mumbai

Varada is an architect from Sir J.J College of Architecture with a background in History and Indian Aesthetics, and extensive experience in the preservation of heritage buildings. At Art Deco Mumbai, she is responsible for the repair and restoration initiatives.

Header Image: Digital illustration by Pranjali Mathure, for Art Deco Mumbai