Facades, like faces, speak of the truth of buildings. They are the avant-garde, the first impression, the point of contact. In them we see the buildings as they present themselves, sometimes with artifice, sometimes shorn of it. But inevitably, we appreciate them as synecdoche, the front representing the building as a whole. In taking up this enterprise of documenting the Art Deco facades of the Oval buildings, in this case Bombay’s most loved ones, we hope to read into the truths of these buildings, now three fourths of a century old, to attempt to see them as they were, in their time.

It took a confluence of several events and trends that made possible the stretch of apartment blocks on the western edge of the Oval Maidan. The site itself had no historical provenance. It was raised out of the sea by the Backbay Reclamations of the late 1920s, and by the turn of the decade plots were available to be built on. The buildings that would eventually come up would face-off a completely different set of edifices on the other side of the commons- the Neo-Gothic collection that included the High Court, the University Library, its Convocation Hall and the Secretariat. These buildings were, by then, half a century old, and fronted an open sea when they were built.

The architects of the new buildings, in the 1930s were of a different generation, both in terms of their education and cultural moorings. The Oval buildings were built by the first generation of Indian architects, trained in the Bombay School of Art, exposed to international practices, having developed a global worldview and appreciative of the new materials and building technologies that were fast becoming available to them. Of these, the technology of Reinforced Cement Concrete and its by products, like cement tiles and Colourcrete were becoming all pervasive, enthusiastically propagated by the cement companies and their association in the journals of architecture and the media in general.

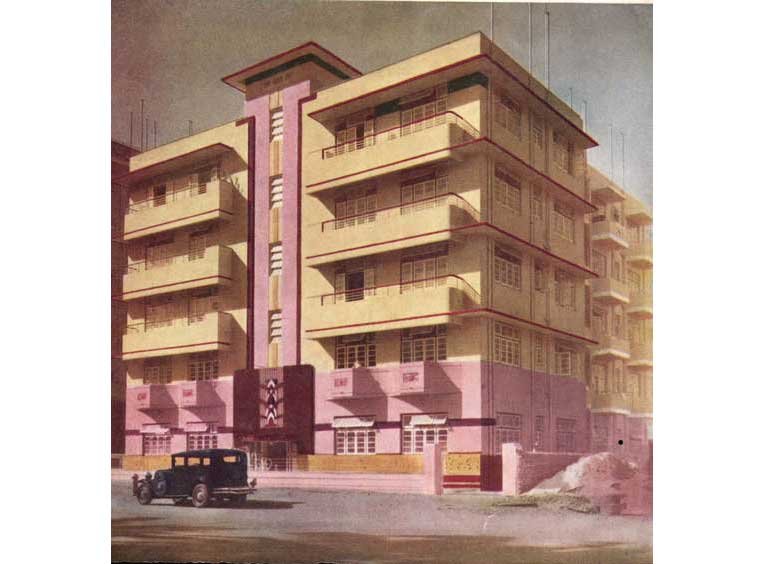

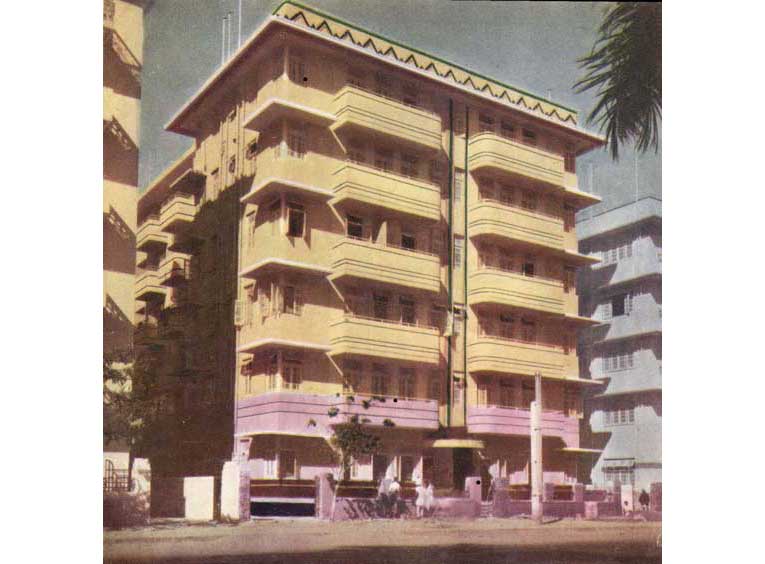

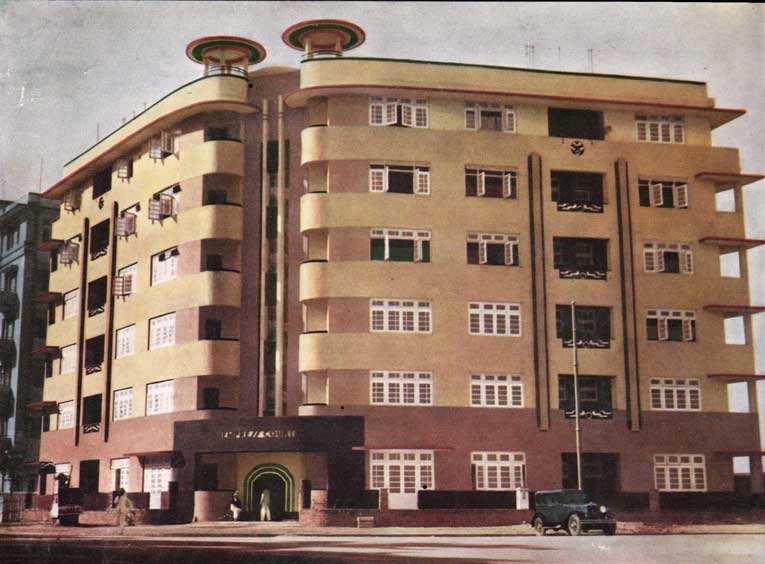

It is interesting to note that a full two decades before Indian independence, Bombay’s architects, Indian subjects of the empire, chose a style of building considerably different from the erstwhile buildings of the Raj to build their own. In a sense, outside the pale of the imperial gaze, they chose an American style, with more affinity to Miami than to London to create homes for their wealthy patrons, who in turn would rent them out to both British and Indian tenants. The style symbolised the global jet-set that no doubt, many of the clients aspired to. Unlike the revivalist proclivity of the colonial masters (whose last short lived exercise had just been completed in New Delhi), this was an architecture of their own time, an international style brought home from American shores by cinema, magazines, and the globe-trotting patrons themselves.

The Art Deco buildings on the Oval are special as they demonstrate, simultaneously, a collective language that creates an urban fabric while individually allowing full vent to creative expression, each competing with the other, either in flamboyance or subdued sophistication. This was the result of building regulations that made all the apartment block toe the same frontage, have the same height and floor lines, a prominent entrance and stairwell and a clear line of flat roofs. The rules, however seem to have liberated the architects rather than stifle them. Even within these framed parameters there is free expression of shape, pattern and symbolism, making these some of the most vocal facades in the city.

At first glance, these buildings are all alike. That is the starting point for understanding them. The facades are self-similar, displaying what Wittgenstein would term as ‘family resemblances’, where the facades are connected by a series of ‘overlapping similarities, where no one feature is common to all’. Each frontage varies from the other like the shake of a kaleidoscope, the same elements yielding different results

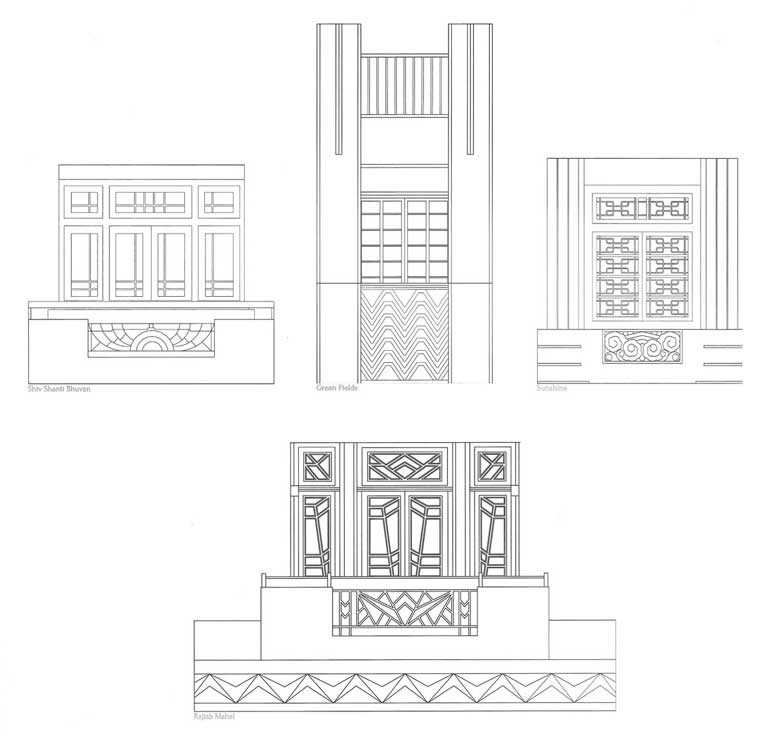

Thus, there are three levels at which these facades can be unravelled for our appreciation. At the first, in terms of their larger form, they are truly alike. As cuboidal forms articulated for living, they follow one of two symmetries, either full-frontal, facing the road, as in the case of Rusi Court/Court View or Green Fields; or are aligned diagonally around a corner, where the building fronts two roads, like Empress Court, or Sohrab/Rajesh Mansion (both of which are depicted in this exhibition as opened out elevations). All the buildings maintain similar floor lines, linking them visually to their immediate neighbours and establishing a continuity on the street.

The second level is that of the architectural articulation of the facades. These, true to the jazz age that is Art Deco’s sometime muse, show variations on a theme. This theme, to give it a name, is ‘streamlining‘ or the curved building element, made possible here by the new technology of concrete. It is to the credit of the architects that, when the Style Moderne (as Art Deco was ‘tentatively’ referred to in its own time) was adopted as a Bombay phenomenon, it was also adapted to the tropical climate of the Konkan. lnstead of the sloping roof and deep eaves, RCC came into its own, protecting the walls with horizontal concrete slab eyebrows (or chajjas) and courageously cantilevered deep balconies and verandahs- in all manner of shapes, curving, rectilinear, angular. The other ‘jazz’ theme, if you will, was the compound design of the entrance/porch/stairwell/tower, expressed differently in all buildings.

The third level is the one we associate with Art Deco the most – the surface, or visual articulation through the use of colour pattern and motif. In archival photographs, taken when these buildings were pristine in their newness, we see a shocking (for our current tastes) exuberance of bright colours and contrasts. In these drawings these palettes are recreated, and take some getting used to. The various tints and hues were the product of Colourcrete, a finishing material popular at the time. Together, these buildings would form a bright and ebullient contrast to the rather dour Neo-Gothic piles visible from their balconies.

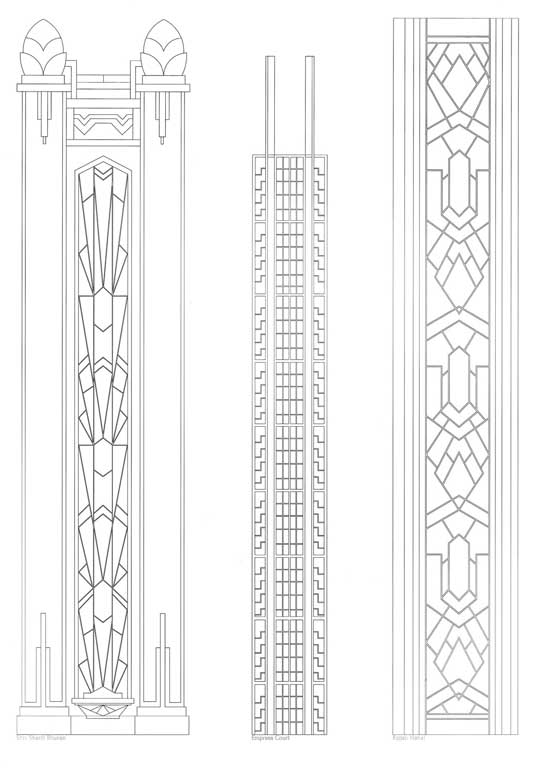

Here too, we observe the coloured patterns and motifs, symbolic relief and building marquees (the prominent building names) that vary widely from facade to facade. These form a narrative syntax that can, for our appreciation, be seen using two words coined for this purpose- ‘enhancers’ and ‘nuancers’. Enhancers are patterns that bring visual richness to the architectural elements – bands, geometrical patterns and horizontal elements ‘enhancing’ balconies, chajjas, roof cornices, railings, window grilles and compound walls, or vertical enhancers around stairwells, towers and entrances. Seen as chevrons, zigzags, waves and stepped (ziggurat) patterns, these are not abstracts alone as they represent various metaphors of speed (automobiles), power (electricity), nautical references (steamships) and travel (steam engines, air ships, aeroplanes) in the international vocabulary of Art Deco. Nuancers, on the other hand, are iconic ornaments seen mostly in relief. Here too they conform to Art Deco conventions, but with a local edge- frozen fountains, flora and fauna, clouds, sea and surf, representations, even an exoticization of Bombay’s tropical locale, its presence as a port city and the proximity of the Arabian Sea. One interesting deviation in the nuancers from international convention is in the choice of some building names that pay obeisance to the colonial power centre- Empress Court, Queen’s Court, Windsor House, even Belvedere Court. This may be referenced to the sudden shakeup in House of Windsor in 1936, at around the same time these building were erected, with the death of George V, the ascension and quick abdication of Edward VIII and his replacement by George VI. This seems to mark these facades in time, for when the Marine Drive Art Deco buildings rise, after the 1940s, we see no such references.

‘Deco on the Oval’ is an exhibition of facades and details, documented as a series of 17 elevations by students of Sir JJ College of Architecture in celebration of this unique architectural blossoming of Art Deco that reached a highpoint in a short half decade and would slowly transform from the 1940s onwards. The present documentation gratefully acknowledges an earlier set of measured drawings of these buildings made by erstwhile students in 1998. The present drawings, however, draw upon an older tradition at the School of Architecture- the creation of ‘reconstructed’ elevations. Using older available material, drawings and photographs, these facades have been drawn as they were when first built. Over the years, in many of these buildings, a floor has been added, and the building fronts modified. Where material is unavailable, educated guesses based on precedents are made. Details, as described earlier have been highlighted, even isolated, so that they can be appreciated by themselves. They form a ludic collection that can, we hope, be put to contemporary use, thus memorialising these wonderful buildings and refreshing their elements at the same time.

In the past year, Mumbai, along with Delhi, has been presented as a potential site worthy of World Heritage status by UNESCO. One of the USPs put forward in this regard is the wealth of Art Deco buildings the city can boast of. As a subset the two stretches (Neo Gothic and Art Deco) on either side of the Oval Maidan are contenders for preservation. This exhibition makes a partial, but substantial case for why this is so. Also, with the current penchant for ‘redevelopment’, one may sound a note of caution. With significant plots of the erstwhile island city transforming from homes to exchangeable real estate, there is a clear and present danger to these buildings too. Sometimes our aspirations and desires can override our sensitivity to preserving our heritage. The last thing we would want is that this documentation remains an archival remnant of a Bombay long lost.

This curatorial note by Mustansir Dalvi, Professor at Sir J. J. College of Architecture, Mumbai, is part of the portfolio that was compiled for the exhibition organised by the college in 2015 titled “Deco On The Oval” – An exhibition on the Art Deco facades of the Oval Maidan.

The note has been reproduced with permission from Sir J. J. College of Architecture and Prof. Mustansir Dalvi. It originally appeared in the monograph publication titled “Deco on the Oval – A Portfolio of facades and Details” that celebrates Bombay’s Best Loved Art Deco Facades and contains 20 plates of the reconstructed elevations and details.’