A medical professional, Karan Hingorani has spent the last ten years in various cities across the US. But it was only when he moved to South End in Boston five years ago that the 32-year-old finally felt “at home.” “Green, with buildings up to three storeys high, this part of the city exudes a sense of intimacy and warmth. When I saw it for the first time, it reminded me of the neighbourhood I grew up in — Shivaji Park,” recounts Hingorani.

The “Shivaji Park culture” is a common refrain one hears from people who grew up in and around the neighbourhood. In her recent book, Shivaji Park – Dadar 28: History, Places, People, noted cultural critic and author Shanta Gokhale too, writes at length about “a sense of place” with respect to Shivaji Park. She elaborates on how this intangible aspect is part of the neighbourhood’s heritage, and fears its loss as one of the largest Art Deco precincts slowly changes due to redevelopment.

But what defines this culture that people speak fondly of, and does the architecture contribute to it in any way?

Looking back at the first two decades of his life that he spent in the neighbourhood, Hingorani believes Shivaji Park feels like a suburb within a city, which sets it apart. “With its various bazaars, traffic and the pace of life, it retains the essence of Mumbai city. Yet, there is a sense of community and people have common interests and hobbies that they pursue together,” Hingorani explains. This is beautifully illustrated by Gokhale in the book, through an anecdote about Sargam, an organisation in the neighbourhood devoted to old film songs. The Hingorani family, which moved to the neighbourhood sometime in the late 1960s, owns the three-storey Neelmani on the quaint MB Raut Road. The son of a Maharashtrian mother and a Sindhi father, most of Hingorani’s memories revolve around the park and their terrace that overlooks it.

“Shivaji Park derives its sense of community also from the fact that the families inhabiting the neighbourhood have mostly stayed back.”

Anand Limaye adds that Shivaji Park derives its sense of community also from the fact that the families inhabiting the neighbourhood have mostly stayed back. The owner of India Publishing Works, Limaye, now 65 years old, has spent his entire life here. A resident of Indu Villa, also on MB Raut Road, he is now publishing a book on their “madhali galli,” aptly titled The Glorious Second Lane. Penned by an advocate and neighbour, it is about the various achievers who lived in that lane, including NV Modak, who played a significant role in the development of the city, especially the neighbourhood.

“we all know each other, having lived here for decades. I am not sure if this kind of unity will be possible once high-rises take over.”

With endless memories of growing up here, Limaye is currently looking for a house as Indu Villa, a cream-coloured three-storey Art Deco building with rounded balconies — almost 80 years old — stands to be demolished in nine months. Limaye fears that the rampant redevelopment will end this sense of community among the Shivaji Park residents. “During the pandemic, residents of all the 30 buildings on MB Raut road functioned like members of a single residents’ group, helping each other — especially the elderly — through and after the lockdown. This was also possible because we all know each other, having lived here for decades. I am not sure if this kind of unity will be possible once high-rises take over,” he rues.

Bombay, as the city was known back in the day, was the first Indian city to witness the emergence of the apartment typology.¹ This typology was then popularised during the development of Dadar-Matunga areas.

The story of Shivaji Park is rooted in the epidemic of 1896. When the Bubonic Plague, also known as Bombay Plague, hit the city, it compelled the British to expand the city limits. Driven by the belief that the plague was caused by sanitation issues arising out of overpopulated native neighbourhoods like Parel and Girgaum, they formed the Bombay City Improvement Trust (BCIT), tasked to decongest the city in a way that would reduce the density of the population and open up the landlocked central and eastern regions to the sea breeze. Bombay, as the city was known back in the day, was the first Indian city to witness the emergence of the apartment typology.[1] This typology was then popularised during the development of Dadar-Matunga areas.

Concentrated efforts were made to draw middle and upper middle class families to a “modern” lifestyle as opposed to the community style living in chawls.

A part of this vision, the development of the Shivaji Park precinct, spread across almost 28 acres, began in the 1920s. The expansive park was thrown open to the public in 1925, and in 1927 the Municipal Corporation officially named it “Shivaji Park” in commemoration of the tercentenary of Shivaji Maharaj. By the 1930s, the land surrounding the park was sold to interested buyers. In his book House, But No Garden: Apartment Living in Bombay’s Suburbs, 1898-1964, Nikhil Rao points out that concentrated efforts were made to draw middle and upper middle class families to a “modern” lifestyle as opposed to the community style living in chawls.[2] And it was Bombay Municipal Corporation’s chief engineer Modak who pushed for the use of new RCC (reinforced cement concrete) technology for cheaper, quicker and sturdy structures.[3]

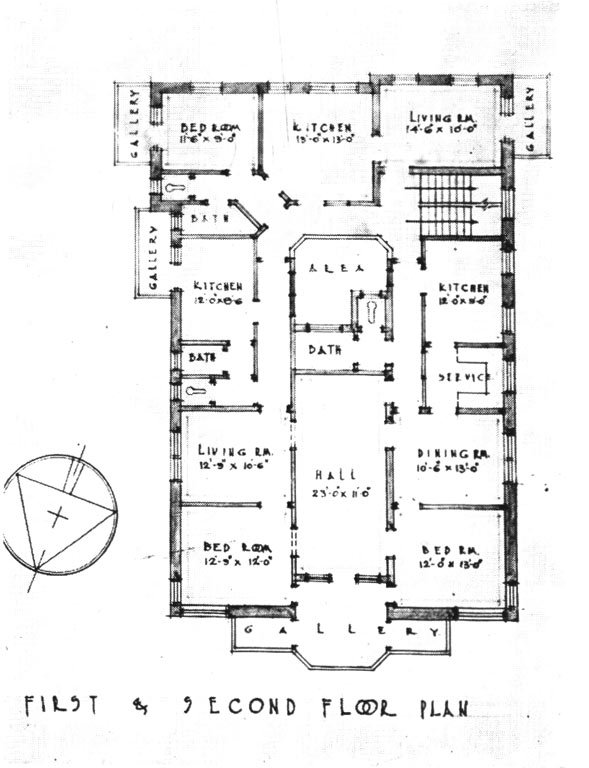

Developed by Indian firms and designed by Indian architects, the buildings that came up in the neighbourhood followed a modest version of the flamboyant Art Deco style that was popular in South Bombay at the time. These were three-storey structures with a living room, a bedroom or two, a kitchen, a bathroom and a toilet. The verandah or balcony was a prominent part of its architecture and the overall design was a compromise between the traditional Indian home and a modern European-style apartment. Rao adds this was made possible due to “the emergence of the first generation of Indian architects ready to build flats suited to Indian tastes”.[4] Over the 1950s and 60s, several cultural institutions mushroomed in and around the park, including the Shree Samarth Vyayam Mandir, an Olympic-sized pool, the Dadar Matunga Cultural Centre and Shivaji Mandir.

Developed by Indian firms and designed by Indian architects, the buildings that came up in the neighbourhood followed a modest version of the flamboyant Art Deco style that was popular in South Bombay at the time.

Prominent architect Neera Adarkar, who has done a study of this precinct, believes that the Art Deco style for Shivaji Park is the consequence of the Indian architects’ sensibility and sensitivity. She points out that the Art Deco elements used in Shivaji Park are a lot more subtle and modest than the flamboyant motifs that can be seen in the Oval precinct, for instance. So the base of the staircases are highlighted with a vertical plaster band in contrasting colour, the windows are rectangular with geometric divisions, and the buildings have curved corners and balconies. “This modesty suits the overall culture of the neighbourhood. The entire environment has everything of modest scale. The planning around a large playground helps cut it off the main road, giving the precinct an identity of its own. Since the precinct came up as a response to the overcrowded neighbourhoods, the Trust’s rules for its development mandated the construction of low density-low rise structures, with plenty of ventilation and sunlight. What you have, as a result, is a neighbourhood that gives a sense of openness,” Adarkar asserts.

“This modesty suits the overall culture of the neighbourhood. The entire environment has everything of modest scale. The planning around a large playground helps cut it off the main road, giving the precinct an identity of its own. Since the precinct came up as a response to the overcrowded neighbourhoods, the Trust’s rules for its development mandated the construction of low density-low rise structures, with plenty of ventilation and sunlight. What you have, as a result, is a neighbourhood that gives a sense of openness,”

Perhaps this openness also mirrors itself in the culture that developed in Shivaji Park, a willingness to explore a new life and nurture new ways. Noted musician Amarendra Dhaneshwar points out that ‘litfests’ were commonplace events in and around Shivaji Park back in the 50s and 60s, well before the term was coined and popularised. Writers, editors, critics, would participate in public discussions over subjects such as censorship. “The 1971 Marathi play Avadhya found itself at the heart of one such debate after its lovemaking scenes caused a stir among the conservative Mumbai audience at the time. There was another on the cover of noted author Shree NA Pendse’s novel. Such talks were open to the public and took place at venues, like the hall at Balmohan Vidyamandir, and Amar Hind Mandal near the Portuguese Church,” says the 68-year-old who continues to live in Shivaji Park. A rare example of a school built in the Art Deco style, Balmohan Vidyamandir is the alma mater of multiple generations of Shivaji Park residents.

Shama Dalwai also recounts the popularity of Vanita Samaj, a women’s organisation in Shivaji Park, which would hold a number of skill-training classes for women, from stitching to cooking. “Soon after Independence, there was a movement to organise women through various mahila mandals. Vanita Samaj was birthed from this movement. One of its members, Kamalabai Ogle, wrote the famous Marathi cookbook, Ruchira, a staple in the bookshelves of a middle class Maharashtrian family even today. Similarly, people in the neighbourhood organised themselves around various common interests, unknowingly contributing to what has come to be known as Shivaji Park’s culture,” explains the 78-year-old activist and social worker.

The daughter of noted intellectual Nalini Pandit, Dalwai lived in Shivaji Park till she got married. With family still there, she continues to visit the neighbourhood that she believes provided her with a holistic childhood and easy access to schools, sporting activities, cultural institutions and, above all, a safe space as both a woman as well as an individual. The neighbourhood, over the last 80 odd years, has been home to some of the greatest stalwarts across fields. Noted vocalist Kesarbai Kerkar, writer Saadat Hasan Manto, cricketers Sandeep Patil and Ajit Wadekar, music director Vasant Desai, actors like Helen and Beena Rai, journalist Leela Jog, noted thespians Arvind and Sulabha Deshpande who laid ground for Maharashtra’s experimental theatre movement through their theatre company Awishkar, are only a handful of such names.

The neighbourhood, over the last 80 odd years, has been home to some of the greatest stalwarts across fields. Noted vocalist Kesarbai Kerkar, writer Saadat Hasan Manto, cricketers Sandeep Patil and Ajit Wadekar, music director Vasant Desai, actors like Helen and Beena Rai, journalist Leela Jog, noted thespians Arvind and Sulabha Deshpande who laid ground for Maharashtra’s experimental theatre movement through their theatre company Awishkar, are only a handful of such names.

What may seem like a sense of nostalgia is to many former and continuing residents of Shivaji Park the precious memory of a neighbourhood that shaped them, both as an individual as well as a professional. “The first time I saw the park full was when the city bid farewell to Yashwantrao Chavan as he gave up his position as Mumbai’s then chief minister to take up the berth in Nehru’s cabinet as the defence minister,” recounts Dalwai. For an 11-year-old, it was an overwhelming sight. Over the following decades, Dalwai witnessed several notable political events at the park, from meetings by the labour unions to Mahaparinirvan Diwas and a rally by JP Narayan ahead of the elections after the Emergency was lifted in 1977. “People view Shivaji Park as Shiv Sena’s homeground when in fact it has been a space where all kinds of groups and political parties have held their meetings and rallies. In so many ways, Shivaji Park gave me the exposure to people’s issues and the various political ideologies that eventually moulded my own ideas,” Dalwai elaborates.

Dhaneshwar too, attributes his career to Shivaji Park, the neighbourhood that gave him easy access to a variety of cultural activities that played a role in his intellectual growth. “Ustad Allah Rakha’s tabla school was (and continues to be) right next to the swimming pool and the maestro himself would perform at the annual function in the school hall of my alma mater Balmohan Vidyamandir. I have watched Zakir Husain and Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma perform in their early years at concerts in the nearby venues. Pandit Ravi Shankar would perform at the Brahman Sahayak Sangh or at the Chhabildas Hall every year. These musicians were not looking for fancy venues but for a discerning audience, which they found in Shivaji Park,” asserts the noted Gwalior Gharana vocalist.

…the aspirations of the middle class who settled here, aided by the facilities and access to a modern lifestyle, may have contributed hugely to what became a pattern — of aiming for excellence.

But what came first — the stalwarts or the neighbourhood that many believe has shaped them? Dhaneshwar is of the view that the aspirations of the middle class who settled here, aided by the facilities and access to a modern lifestyle, may have contributed hugely to what became a pattern — of aiming for excellence. “We were able to meet and interact with these people at a personal level. For instance, I was a huge fan of Acharya Atre (educationist, activist and orator Pralhad Keshav Atre). I would follow him around during his evening walks at Shivaji Park. He would also entertain me and speak at length about his ideas,” he points out, “This is the Shivaji Park culture that we residents boast about.”

“Heritage is not only history or a slab of concrete and architecture; it is also the quality of life. But the onus of preserving this heritage falls primarily on its residents.”

Such conversations, which would often take place at the periphery of the park, atop its low boundary wall — also known as the ‘katta’ — is the likely origin of the concept by the same name. A Maharashtrian equivalent to the Bengali ‘adda’, ‘katta’ has emerged as a synonym for an exchange of ideas among a group of diverse people. “And this is the heritage that is worth preserving,” says Adarkar, who worked on a report to defend the heritage status of Shivaji Park’s Art Deco precinct that has been under the threat of redevelopment. “Heritage is not only history or a slab of concrete and architecture; it is also the quality of life. But the onus of preserving this heritage falls primarily on its residents. Architects like me can suggest alternatives but it is the people who directly benefit from it who will have to defend what is Shivaji Park’s true heritage — its culture.”

Dipti Nagpaul for Art Deco Mumbai

Dipti is a Mumbai-based journalist. With over a decade’s experience, she has written for The Guardian, Vice, The Indian Express and Oxford Urbanists, among others. Her love for the city drives a large part of her writing even as she covers a variety of subjects, including caste, gender and the politics of culture.