Abstract

This paper traces the development of a modern urban sensibility in the practitioners of architecture in Bombay in the decades before the Nation State. Largely home-grown, they embraced a form of international Modernism. The architecture of the time was prolific but was in contrast to imperialist monumentality. The writings of the 1930s and 1940s that follow these developments are often polemical, pragmatic and even contradictory; but unabashed and outspoken. Both architects and laypersons vigorously debated and argued in public lectures and meetings what Claude Batley would call ‘This New Architecture’. Journals and books would disseminate new ways of living and building that were influential in Bombay and all over India. Cement companies would be at the forefront, disseminating products by publicising notable examples of architecture built every year. It is this ‘new architecture’ that has retrospectively been labelled ‘Art Deco’. This non-monumental, functionalist architecture for contemporary needs defined the urban image of the emerging metropolis. This paper charts these transitions through the voices of the protagonists themselves.

Introduction

In the last two decades before India gained independence, an urban sensibility, essentially modernist in outlook, established itself in the zeitgeist of Bombay.1 This was manifest in the huge output of architecture and urban placemaking, largely the work of architects educated in Bombay and their mentors. In contrast to the imperial architecture of the British, whose programmatic monumentality was breathing its last gasps in the buildings of New Delhi, Bombay’s home-grown architectural fraternity embraced modernism with design that was both international in outlook and contemporaneous in sensibility. Their architecture incorporated emerging materials and construction technology to create buildings for their time, incorporating the latest services to cater to an urbane lifestyle.

Architects and interested laypersons alike vigorously debated, argued, critiqued and defended the changing architecture of the changing city. The main vehicle of their deliberations was the Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects (JIIA). Public lectures, seminars and meetings were held frequently to discuss and debate what Claude Batley would call ‘This New Architecture’.

These buildings are significant because they define an urban rather than a monumental scale and display a functional purpose creating neighbourhoods and business precincts in the metropolis. As a collective, these buildings, interwoven within the older areas of the city and providing newer edges to it, created a fresh urban fabric that united the city visually, giving a sense of place to its inhabitants. It is the same fabric that defines a large part of the city today, having been in continuous use since the early 1930s.

This paper traces the development of Bombay’s architecture in the 1930s and 1940s by an analysis of various published writings and texts from the same period. Through the discussions of architecture and modernity that its practitioners were steeped in, contemporary and contradictory voices articulate the architecture of their time even as the city was undergoing rapid urban change.

Architects and interested laypersons alike vigorously debated, argued, critiqued and defended the changing architecture of the changing city. The main vehicle of their deliberations was the Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects (JIIA). Public lectures, seminars and meetings were held frequently to discuss and debate what Claude Batley would call ‘This New Architecture’. Publications brought

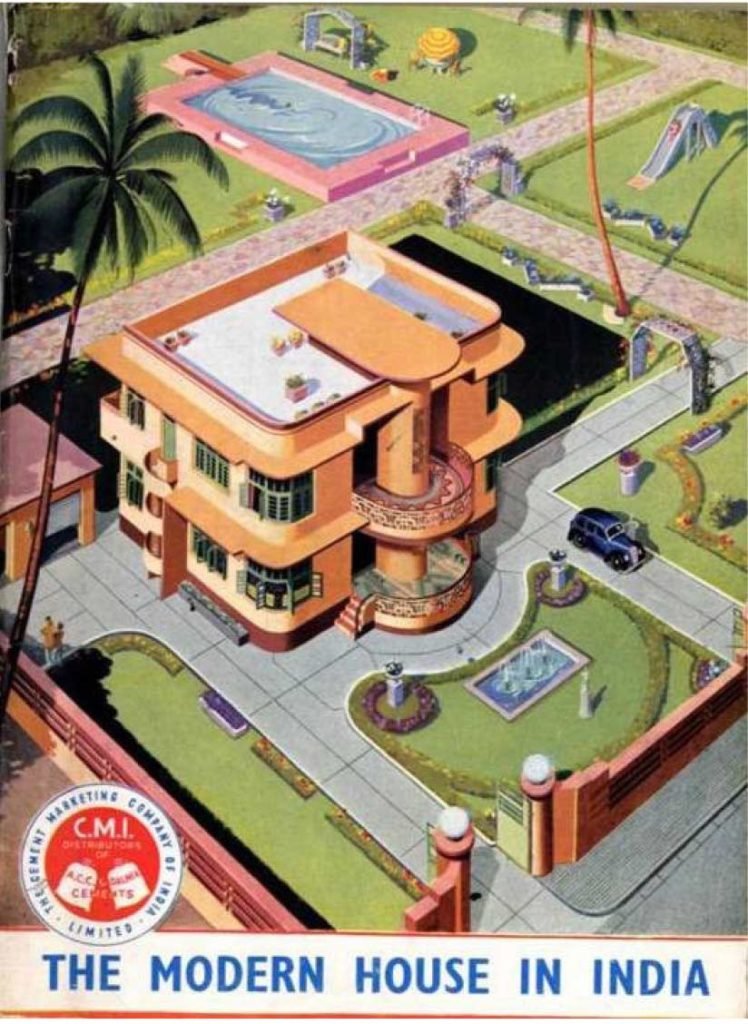

out at the time, particularly those by Batley, R. S. Deshpande and the annual ‘The Modern House in India’ series by the Cement Marketing Companies of India would widely disseminate the new ways of living and building that had an influence on architects and their prospective clients not only in Bombay but all over the major cities of the country.

These texts allow for the creation of a historical chronology that sets right generalizations about architecture in Bombay during those unique decades. Architectural writings from the 1990s onwards have underplayed the architecture of Bombay before national statehood as somehow inferior or copied (Chatterjee, 1985; Lang, Desai, & Desai, 1997). These writings imply a hesitant kind of Modernism waiting for the arrival in India of the foreign Modern masters for legitimacy. Yet, Bombay’s Indian firms were practicing a version of international modernism two decades before India gained freedom. These practices would continue well into the 1960s. The great Modern masters, at least in the initial years, had no significant impact on Bombay because the city already had a tradition of Modernism for the last quarter century or so.

Bombay’s urban image, the one that is recognized today, started to take shape from the 1920s. New developments that fired the city’s contemporary image included, not only the laying out of new neighbourhoods and precincts outside the boundaries of what was then known as the Inner City but also within the city itself in the form of new avenues lined with newly built apartment houses and bungalows.

The Ubiquity of Middle-class Architecture in the 1930s and 1940s

Nearly two decades before nationhood, Modernism took root specifically in middleclass, mass architecture. This changed sensibility spread far and wide in a short span of time and could be seen in Bombay, Poona, Ahmedabad, Surat, Indore, Delhi, Kanpur, Aligarh, Karachi, Lahore, Calcutta, Patna, Dacca, Hyderabad (Sind and Nizam), Bangalore, Madras, and Coimbatore amongst others as can be discerned from the pages of publications brought out by The Associated Cement Companies Limited. In all these places, the architecture was surprisingly nonregional and largely self-similar.

The spread of architects trained in Bombay (at the Sir J.J. School of Art) all over the Dominion and the Princely States is highlighted in an obituary in the JIIA for Robert William Cable, who was the first head of the Department of Architecture at the school. Claude Batley, the editor, compares Cable indirectly to Christopher Wren by saying “although he left few buildings of his own, the great bulk of the better and more scholarly architectural work built in Bombay during the last few years has been designed by those who were his students […] trained by him are practising in many other districts in India, as far afield as Lahore, Delhi, Madras as well as in Burma and Ceylon.” (1937, p. 279).

Bombay’s urban image, the one that is recognized today, started to take shape from the 1920s. New developments that fired the city’s contemporary image included, not only the laying out of new neighbourhoods and precincts outside the boundaries of what was then known as the Inner City but also within the city itself in the form of new avenues lined with newly built apartment houses and bungalows. Land was at a premium, despite the emergence of new northern suburbs and the schemes of the City Improvement Trust, meant that the apartment block in a residential precinct became the preferred choice of ‘upper-class’ urban habitation. This extensive activity of housing would be the critical layer superimposed on the palimpsest Bombay that would hold its own within the traces of native settlement and the dominion architecture within the Fort precinct.

Architecture in the Emerging Metropolis

Bombay’s architecture of the decades before independence has to be seen in the light of what came before it. During the city’s rise as a commercial and financial capital, the buildings that defined it were its public buildings, built to consolidate the dominance of the Raj on the rapidly developing Urbs Prima in Indis. The imperial exercises in power-building reached their apogee in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, paralleling the city’s rise as a mercantile power in the wake of the American Civil War (1861-65), and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Imperial architecture would continue into the first decade of the twentieth century. The grand public buildings of the city included the railway stations, administrative buildings, town halls, universities, museums and hospitals- showpieces to the imperial order on an urban scale. Once these were done however, there would not be much addition to the city in the form of government buildings. What came next were exercises in urban planning and consolidation, insertions and extensions to the existing city to accommodate the changing demographics of an upwardly mobile citizenry.

Bombay-trained architects designed for the city’s contemporary needs. These would include new office buildings, cinema houses and various types of domestic architecture. Some of the wealthier Indian clients, like Rajab Ali Patel, even built apartment blocks to rent out to Englishmen who had settled in Bombay to make their lives and careers.

In the development of Bombay, the relationship between the British and Indians was quite unique, unlike that in most other cities. Indian hands wielded Bombay’s mercantile strength, and British interests in the same hands often suborned this authority. The expected relationships flip-flopped without causing any undue concern to either side, thus allowing for the breathing (creative) space for Indian architects to operate in. By this time, the commercial clout of the city, the city’s wealth was in the hands of affluent Indians, the influential elite in Bombay, rather than its colonial masters. Here the relation was much more that of equals and quite symbiotic in nature. These were the well to do, educated (in the western tradition), upwardly mobile, globetrotting and ocean voyaging cosmopolitan citizens of Bombay, who made wealth and displayed it with ostentation. The most outward trapping of this state was the construction and habitation of a better form of domestic space.

The architecture that came up around that time was unique in the sense that it was “… not imposed on the city by a government, as was the case with the Neo-Gothic, but was embraced by the citizens.” (Pal, 1997, p. 14). Bombay-trained architects designed for the city’s contemporary needs. These would include new office buildings, cinema houses and various types of domestic architecture. Some of the wealthier Indian clients, like Rajab Ali Patel, even built apartment blocks to rent out to Englishmen who had settled in Bombay to make their lives and careers. Richard Bently, as far back as 1852 would observe that “the principal dwelling houses in the island are now owned by Parsee landlords, and are either inhabited by themselves, or let out at high rents to the English residents, who are rarely inclined to involve themselves in the troubles and responsibilities of land proprietorship.” (Evanson, 2000, p. 167).

Contemporary Urbanity Generated by the Schemes of the City Improvement Trust

In 1898, the City Improvement Trust was constituted by an Act after the ravages of the bubonic plague in 1896. The Trust was entrusted with the work of making new streets, opening out crowded localities, reclaiming land from the sea to provide room for the expansion of the city, and to build hygienic homes for the less affluent. This necessitated a newer type of building, one that was urban, situated, as it were, close to the action of the throbbing organic metropolis. Land being at a premium, despite the emergence of new northern suburbs and the vast schemes that were the result of the City Improvement Trust, meant that the apartment block became the preferred choice of affluent urban habitation. Domestic architecture in Bombay that would emerge in the early twentieth century would exemplify this typology.

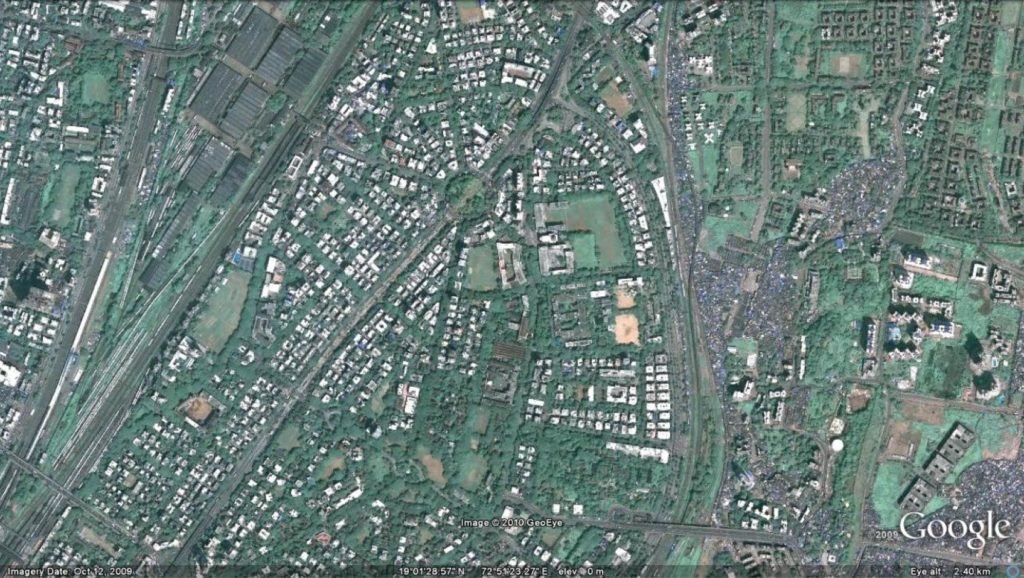

Various schemes of the Improvement Trust and the opening up of suburban areas also provided facilities for middle class housing. In the 1920s, housing schemes were floated to offer householders facilities by providing subsidies. A successful scheme among these was the Dadar-Matunga Estate -the Parsi and Hindu colonies on either side of the Kingsway (Figure 1). Most buildings in these areas were designed either by qualified architects or civil engineers who retained architects for the design of exterior elevations and architectural details (Iyer, 2008, p. 288). Another type of housing prevalent at the time was by various charitable trusts; schemes such as Cusrow Baug, Rustum Baug, and the Gamadia and Cowasji Jehangir colonies. They provided for the lower middle class at reasonable rents and maintained open spaces and other facilities within their boundaries.

In the Trust areas, a fourth of the area was reserved for roads and open spaces for all. Only one-third of the plot area was permitted to be built. Layouts and planning norms of areas within the Improvement Trust were strictly restricted and regulated. This would ensure uniformity in the heights and proportions of the walls, and other features. Thus differently designed buildings came up but collectively these gave a sense of harmony and continuity on the streets they were built upon (Iyer, 2008, p. 288). The Improvement Trust would also provide for playing grounds and recreation areas, and paved footpaths as soon as buildings were constructed (Kapadia, 1937, p. 259).

These new developments reflected the needs of the day – the rapidly modernizing impulse, a new lifestyle of professionalism and mercantilism that consolidated the port city in the early decades of the twentieth century. The creation of this architecture at a ‘domestic’ rather than monumental scale laid out over vast areas of the city changed its image into all inclusive, dynamic metropolis.

In all, the City Improvement Trust developed the precincts of Sion, Parel, Dadar, Matunga, Mohammed Ali Road, Byculla, Nagpada, Princess Street, Sandhurst Road, the Backbay (after the reclamations of the late 1920s and 1940), the Princess Dock, Elphinstone Road, Colaba. Architecture, such as it would be, would now cater to the individual householder or entrepreneur- and their families, at work and at play. These new developments reflected the needs of the day – the rapidly modernizing impulse, a new lifestyle of professionalism and mercantilism that consolidated the port city in the early decades of the twentieth century. The creation of this architecture at a ‘domestic’ rather than monumental scale laid out over vast areas of the city changed its image into all inclusive, dynamic metropolis. Buildings from the 1930s onwards, designed functionally with modern construction techniques would give Bombay its lasting cosmopolitan image of urbanity that one associates with it even today. These humane precincts and urban stretches form part of the unique heritage of Bombay’s recent past.

Bombay’s Home-grown Architectural Practices

These new constructions were driven both by the predominance of new building materials- cement and its offshoot technologies, as well as by the designs of the educated professional architects who oversaw them. The result of this association was the adoption and dissemination of a new form of architecture catering to a new form of urban living that can rightly be called the first flush of modern architecture in Bombay.

The 1930s and 1940s were prolific years for architecture in Bombay. Lovji Shroff, in his Presidential Address at the Indian Institute of Architects (IIA) delivered on 7th June 1934, described several examples of buildings just completed that would in time be the definitive examples of modern architecture in Bombay:

“It is very gratifying to note the recent spurt in building trade after a rather prolonged lull. The blocks of building at Colaba Causeway Road known as “Cusrow Baug” recently erected by the Trustees of the Nowrojee N. Wadia Trust from the designs of Messrs. Gregson, Batley & King, show remarkably well what a layout from a housing scheme should be like from the hygienic point of view […] Amongst works of Architectural merit recently erected in Bombay may be mentioned the Regal Theatre close to the Prince of Wales Museum by Mr. Charles Stephens, and Mr. A. E. Ghaswala’s building at Phirozeshaw Mehta Road by Messrs. Bhedwar & Bhedwar. Besides these there are many smaller buildings of Architectural merit recently put up in Indian and other styles on Mahomedalli Road and in the Hindu and Parsi Colonies at Dadar. We welcome the marked advance in architectural quality in the designs of these buildings.” (Shroff, 1934, p. 47)

By 1937, these building activities had energised the city with an ‘unprecedented building boom’, the result of large areas of land, unavailable before, coming into the market for outright sale or temporary lease offered by the Bombay Municipality, the Government of Bombay and the Port Trust. In particular, buildings on the three stretches of South Bombay, the Cooperage, the Phirozeshah Mehta Road and the Marine Drive (having been leased over) were rapidly being constructed. Even such public buildings as the Reserve Bank of India and the Electric House at Colaba had begun construction. The Electric House was to be “a first-class building built on modern lines with up-to-date arrangement and air conditioned throughout.” (Kapadia, 1937, p. 258) (Figure 2). These new constructions were driven both by the predominance of new building materials- cement and its offshoot technologies, as well as by the designs of the educated professional architects who oversaw them. The result of this association was the adoption and dissemination of a new form of architecture catering to a new form of urban living that can rightly be called the first flush of modern architecture in Bombay.

Bombay’s architects had been educated in the western tradition, some in the west (by becoming Fellows of the Royal Institute of British Architects) and were as forward looking and eclectic as their paymasters. They believed in Modernism’s essential agenda and sought to demonstrate it in their own work, transforming a port city into a world city (Dalvi, 2004, p. 45). They were also aware of the influential architecture and literature of Modernism. Mistri and Billimoria, in a review of architectural development in the previous twenty-five years published in the JIIA in 1942 would propose a future architecture for the city, using the rational theories of Le Corbusier and other European modernists:

“It is not enough that our architects are free from the vanity of ‘styles’. They must learn to exploit and apply the fruits of scientific research in their day-to-day problems… The building is a machine to live, work or play in […] Architecture has changed from the art of two-dimensional pattern making to the science of the relation of space and movement […] Orderliness is the beginning of everything.” (p. 223)

Claude Batley and ‘This New Architecture’

Claude Batley, Principal of the architectural firm Gregson, Batley and King and Professor of Architecture at the Sir JJ School of Art, Bombay (1923-43) was the most prolific commentator on the architecture of Bombay. In a lecture delivered at the Indian Institute of Architects on October 4th 1934, he spoke of emerging trends, of what he described as ‘This New Architecture’ as a return to primary essentials. In his speech he was unabashedly critical of the revivalist and neo-Classical stylistics that were the hallmark of the architecture of officialdom until this time:

“This New Architecture is in one sense the nudist movement in our profession. […] Look at any facade on the West side of Hornby Road, in our own Bombay, and any reasonable man would agree that it would be transformed for the better if one of us took an axe and chopped off every bit of ornament […] surely it is more dignified for the architect to take his place in the vanguard of progress, serving his own day and generation, in its own spirit…” (Batley, 1935, p. 103).

Batley went on to speak about the changing ways of life that were the outcome of strained circumstances during the (First World) War, which resulted in greater gender equality. In addition there were technological advances and several labour saving devices that needed to be incorporated in the architecture that was to come. Functionalism had been an inspiration for the New Architecture. This, along with the new materials available at the disposal of contemporary architects like cement and its by-products like “big-six” synthetic marbles and stones, with plywood and “celotex”, aluminium and “staybrite”, asphalt and wired glass. Batley suggested that the very efficiency of these new materials would give the new architecture a ‘beauty that comes out of truth’, also invoking Le Corbusier’s functionalist credo: “architecture is but the creation of perfect, and therefore also beautiful efficiency and that, as Corbusier says, ‘A house is a machine for living in.’” (Batley, p. 104).

Claude Batley, Principal of the architectural firm Gregson, Batley and King and Professor of Architecture at the Sir JJ School of Art, Bombay (1923-43) was the most prolific commentator on the architecture of Bombay.

In the debate that followed, Batley was countered by D. N. Dhar, who condemned the new fashion as being only another type set to copy from abroad, full of corrupt mannerisms and entirely un-national from an Indian point of view. Batley, in turn, was unapologetic about the emerging architecture, replying that “… to consider it un-national was a very great mistake, for its success rested entirely on functionalism, and would have to be studied in India from that point of view alone, in which case it must, subconsciously at least, take upon itself an Indian character.” (p. 104). This exchange demonstrates both the optimism and the scepticism of the times, and the free interaction of viewpoints that would help reinforce the changing ways of the city.

Batley of course was not alone in articulation or practice. Just a few among Bombay’s many were the firms of Poonegar and Mhatre; Master, Sathe and Bhuta; Bhedwar & Bhedwar; Merwanji, Bana and Co.; Sykes, Patkar and Divecha; G. B. Mhatre; Yahya Merchant and Abdulhusain Thariani. These practices aspired to reinvent the urban image of Bombay in an image of modernity.

Batley of course was not alone in articulation or practice. Just a few among Bombay’s many were the firms of Poonegar and Mhatre; Master, Sathe and Bhuta; Bhedwar & Bhedwar; Merwanji, Bana and Co.; Sykes, Patkar and Divecha; G. B. Mhatre; Yahya Merchant and Abdulhusain Thariani. These practices aspired to reinvent the urban image of Bombay in an image of modernity. The new architecture was a symbol of affluence that fulfilled the desire of Indian clients to imitate the lifestyles of the many princes, like the palatial Modernist homes of Manik Bagh in Indore (1933) or the Umaid Bhavan in Jodhpur (1929-43).

The influence of ‘l’espirit Moderne’

S. Deshpande was a prolific author of several popular books on contemporary architecture in the 1930s and 40. His writings were primarily aimed at the layperson and aspiring homeowner. Through his writings he espoused a modernist viewpoint. Modern Ideal Homes for India (1939) was a manual for building written for those who did not have access to professional architects. For Deshpande, “a good house must exactly suit the family, just as clothes to the wearer.” (p. 4). He had little value for ‘external embellishment’ and felt that “overflowing elaborate architectural features contribute very little towards making a house comfortable.” All over the West, a change in domestic architecture, almost revolutionary in character was taking place, so how could Indians escape them? He invoked the modernists – Le Corbusier, Gropius and J. P. Oud, even the Russian Constructivists who rose in revolt against traditionalism, dubbing it ‘a dishonest expression of academic falsehood’. He confessed to being convinced by the merciless logic with which they expressed their ‘astounding views’ that reached India through books and articles in Western journals.

Deshpande, wanting a first-hand appreciation of these Modernists went on a tour of several of these buildings during 1936-37, and concluded that “it was not a revolution sweeping over the Western countries, but a natural inevitable evolution.” (p. 4). His book is a result of his efforts to ‘Indianize’ modern ideas, and to adapt and modify them to suit the climatic conditions and the social conditions of the people of India.

In his attempt to define ‘Modern Architecture’, Deshpande claimed that it has no characteristics of its own, beyond being simple and in harmony with modern ways of thinking and modern ideas of hygiene, an architecture rationally related to the circumstances of modern life. The extreme functionalist ideal (that architecture does not exist, only functions exist; or there is no Art of Building, only building) may be too much to be applied in a dogmatic manner: “No architect of the first rank now practises pure functionalism. One good thing however, came out of this movement, viz., that it emancipated the architect from stylism.” (p. 69). The l’espirit Moderne essentially consisted of functionalism and simplicity and devising new methods of construction to suit new materials. This architecture was most suited to our country, as it was in keeping with the philosophical ideal of plain living and high thinking. It catered equally for the rich and the poor (p. 70).

The Mass Popularity of RCC Fuelled by the Promotions of the Cement Companies

In 1935, R. S. Deshpande would acknowledge that “indigenous cement of the best quality is becoming cheaper every day, and the most efficient organisation of the Concrete Association of India is always ready to give free advice”. (Deshpande, 1935, p. V). The Concrete Association of India was formed in 1927 as ‘a central clearing house of information and technical data’ on all matters pertaining to the many uses of cement and concrete. The association was the technical organisation of the Cement Marketing Company of India Ltd., who were the distributors for all brands of cement manufactured by the ACC and Dalmiya groups of Companies.

Cement companies in India fuelled the mass popularity of functionalist architecture by the vigorous promotion of RCC. These companies had well organised publicity departments that released brochures and ‘folders’ that compiled photographs of newly finished buildings, both domestic and public, from the major cities and princely states in India.

The new material of Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC) was well established in the architectural practices of the country by this time. Cement had become an ‘Indian’ material since 1914, when it started to be manufactured in Kathiawar. By the end of the 20s, there were cement manufacturing companies in Wah, Lahore, Delhi, Banmor, Lucknow, Lakheri, Karachi, Kymore, Katni, Mehgaon, Porbandar, Nagpur, Calcutta, Bombay, Shahbad and Madras, each equipped with modern plants making Portland Cement that exceeded the requirements of the British Standard Specification (Moncrieff, 1929, p. 1). Architectural practices in Bombay ‘specialising in concrete’ included Desai, T. M.; Gregson, Batley & King; Hormasjee Ardeshir; Merwanjie Bana; Mistri & Bhedwar; Patel & Barma; Shahpurji N. Bhuchia and Taraporewala Bharoocha & Co.

Cement companies in India fuelled the mass popularity of functionalist architecture by the vigorous promotion of RCC. These companies had well organised publicity departments that released brochures and ‘folders’ that compiled photographs of newly finished buildings, both domestic and public, from the major cities and princely states in India, displaying the technology and aesthetics made possible by cement in their construction (Figure 3). This is how the virtues of concrete were advertised by the Cement Marketing Company of India: “Concrete gives the maximum service for a minimum expenditure” or “Curved or squareit’s equally easy for concrete.” (The Modern House in India, 1942)

The examples of buildings from the 1930s showed the popularity of this new form of building and the extensive spread of the new technology. A single year’s collection of these folders would encompass several examples of new buildings from Bombay, Poona,

Ahmedabad, Surat, Morvi, Udaipur, Indore, Hyderabad, Secundrabad, Tuticorin, Bangalore, Lahore, Patna, Calcutta, Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Assam, New Delhi, Kanpur, Aligarh, Karachi, Madras, Coimbatore, Aleppy, amongst others.

Architecture constructed in RCC would soon become the standard, whether for bungalows, apartment blocks, office buildings and even palaces. It is through these publications that we can see the long reach of this technology and the popularity of the architecture that it engendered.

Architecture constructed in RCC would soon become the standard, whether for bungalows, apartment blocks, office buildings and even palaces. It is through these publications that we can see the long reach of this technology and the popularity of the architecture that it engendered. Significantly, most of the firms that these cement companies were putting on display were from Bombay, most commonly firms like Gregson, Batley and King; Master, Sathe and Bhuta; Merwanji, Bana and Co.; G. B. Mhatre; Doctor, Mhatre & Desai; Poonegar & Mhatre; Yahya Merchant; Pastakia & Billimoria; Bhedwar & Bhedwar; K. P. Davar & Co.; Abdulhusain Thariani amongst others. Additionally, building contractors such as Gannon Dunkerley & Co.; Shapoorji Pallonji & Co. and Motichand & Co. were also featured. These firms’ reach in terms of both practice and prolificity, spanned not just their city but the entire country.

Proselytising and Dissenting Voices

Until the late 1920s, residential buildings, even multi-storey buildings were built with brick load-bearing walls over stone masonry plinths and crowned with pitch tiled roofs that were costly to maintain. Flat roofs built in concrete would become popular with architects from the 30s onwards as an easier and acceptable option, and also one that was associated with modernity (Iyer, 2008, p. 288). Buildings constructed thus would be both efficient in terms of planning, require lesser materials as compared to the more bulky load-bearing constructions, as were practised earlier, allowed for a variety of forms and fenestration. In their review of construction and materials in the JIIA, McKnight and Kapadia (1934, p. 79) would redefine the architect as a “modeller with his clay […] now moulding concrete – a material which is easily plastic – in a truly artistic and colourful manner into any shape that may be needed to meet the structural requirements of the building under construction, or to suit its environment, and the artistic tastes of the most critical clients.”

Offshoots of cement technology included finishing materials such as ‘snowcrete’ and coloured cements. Buildings could now take ‘artistic lines’, as “All the objections as to plainness and lack of colour have been overcome in the realisation of the possibilities of a material which is now not only easily handled but made in a variety of most attractive colours […] The present age demands colours – up-to-date internal decorations are bright and cheerful and suggest gaiety…” (1934, p. 80). Seeing these buildings today, more or less intact, after more than half a century, one can appreciate the assertion that the vitality that these new coloured buildings brought to a dour urbanscape, by putting forward a far more lively and fresh visage fuelled demand, and created a widespread acceptance.

While the New Architecture had its unabashed supporters, it had its fair share of detractors too, both from within the community of architects and beyond. The debate for what architecture was good, appropriate and ‘Indian’ was engaged in public fora in Bombay, and within the pages of the JIIA. Kanhaiyalal Vakil was a noted journalist and a long-term well wisher of the Institute who delivered several critical lectures at their behest. In a lecture delivered before the IIA on 7th November 1935, Vakil expressed his apprehensions both for the flamboyant ‘revivals’ as well as the style moderne, which he considered was ‘borrowed’.

“The cleverly forced mannerisms of the decadent style moderne may be observed by any intelligent eye. The ubiquitous terrace balustrades with streamed bars, the unprotected mid-air projections, the garish colour and decoration are more than indicative of the indiscriminate ransacking of catalogue modes. This naval architecture, if it could be so called, for stationary structures, the projection uncovered to the blazing sun and the monsoon downpour, are illustrative of the grotesque and imitative decadence.” (Vakil, 1936, p. 79)

Vakil, in his critique lists out the very features that were commonly being adopted all over the city. The ‘naval’ architecture, the streamlining and the modern geometrical forms made possible by the use of RCC were, of course, used with ‘gay abandon’ by architects. They also modified the architecture to better adapt to local conditions and shield the sun and rain with daring canopies and overhangs in concrete that are the calling card of the architecture of their time. These adaptations can be seen in architecture all over Bombay built in the 1930s and 1940s, from the Oval Maidan stretch to the Marine Drive, from the erstwhile Hornby Road to the Dadar-Matunga estates.

It would also take some time before the new way of group living in ‘flats’ or apartments would be completely accepted. Hansa Mehta speaking to the members of the IIA on 6th February 1936 rued that the art of domestic architecture has become a lost art in India. She wished for flats to be so constructed “as to give real home comforts instead of making one feel that they are temporary abodes to be changes as soon as something better turns up. This unsettled feeling is very much due to the bad architecture…” (Mehta, 1936, p. 115). The new line of ‘flats’ that came up across the Oval, facing off the line of older Gothic structures that included the High Court and the University buildings, the same group of buildings that is today most revered as the best set of Art Deco buildings in the city, was not beyond criticism either.

Even within the pages of the JIIA, the unveiling of these buildings (Figure 4) with their ‘modernistic style of elevational treatment’ was deplored for their planning, for the “the inadequate provision of wide and spacious verandah and balcony accommodation which is so marked a feature in the older residential buildings. We are inclined to the belief that the architects have attempted to cram too much […] The rooms in our opinion are too small and the ceiling heights inadequate for residential quarters intended for good class tenants.” (Ditchburn, 1936, p. 176).

The Post-Facto Appellation of ‘Art Deco’

The ‘New Architecture’ that was built and debated upon in the penultimate decades before India gained nationhood, would in time be remembered as ‘Art Deco’. This term is established today but it is a post-facto appellation. During the period between the two World Wars, an eclectic design style developed in Europe and the United States that later became known as Art Deco. The name was derived from the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs Industriels et Modernes held in Paris, which celebrated living in the modern world. Today, Art Deco is used to refer to a mix of styles from the 1920s to the 1940s. From the stepped skyscrapers of New York and the exuberance of the Hollywood/Jazz age to the hotels of Miami Beach, the architecture of the period contributed to the language of Art Deco design.

In Bombay, the Art Deco era was one of contradictions. Bombay’s architecture during the time was formed broadly of two types: One was highly ornamental, a direct import of an architectural style from the US, as applied to the cinema houses of Bombay. This Hollywood style, a gesamtkunstwerk (total design) was shown off best in the Eros, the Regal, and the Metro as well as in a few office or commercial buildings (Dalvi, 2000, p. 16). These elaborately finished cinema houses, with their idiosyncratic interior spaces and in-your-face exterior forms extended the fantasies offered by the films themselves. These buildings expressed the corporate branding of various American cinema companies like Metro Goldwn Mayer and United Artists Worldwide, like the McDonalds of today, and perpetuated the image of glitz and tinsel. Bombay’s extended obsession with the movies received its first boost, as by 1933 Bombay possessed more than sixty cinema houses (and nearly 300 by 1939) including seven talkies, located in traditionally styled buildings (Alff, 1997, p. 251).

The other, a more muted Modernism, was of course, ‘the New Architecture’, seen in residences and offices along the Oval and the Queen’s Necklace at Marine Drive, or the Bombay Improvement Trust areas. The residential buildings of the 30s metamorphosed the urban cityscape of Bombay to a characteristic cosmopolitanism, covering vast areas such as the Matunga, Parel and Dadar estates, and some of the older precincts of south Bombay. Building designs here was restrained and shared many of the qualities of purist Modernism.

The exterior facades of the residential structures could be seen as a consumerist or fashionable, rather than a pervading style, acceptable at the surface level by the growing upper middle classes of the day. In the majority of Bombay’s buildings from the 30s, there is closeness to Miami’s Deco precincts, but with much more restraint. Here, Deco(rative) styling is integrated through the exteriors of the building as well as boundary walls, entrance gates, vestibules and lobbies as well as stairwells of apartments. The design of apartment layouts here arranged around rigid double loaded corridors, with servant areas and side entries distinct and separate (Dalvi, 2000, p. 16).

Art Deco was Modern in terms of new technology (RCC), new materials and new ways of living but without the ideological polemics later associated with many Modernist architects. Its tectonic impulse is similar to Modernism, even if the poetic impulse is different. The style was adopted, and then adapted in a uniquely Indian way, suitable for Bombay’s climate as well as an Indian sensibility and lifestyle. Adapting the prevailing style in the U.S. epitomizing a modern, jet-setting, cosmopolitan life, Art Deco in Bombay symbolized an upwardly mobile status and gave a sense of moving beyond both tradition as well as dominion, allowing Bombay’s architects to replace the old with a new International order.

An unstated (although implied) objective of this paper was to search for, among the

varied and sometimes cacophonous voices of the architects and other critics of the time, a semantic, a definition or a name for the kind of buildings being designed in Bombay in the decades preceding the Nation State. A well-known appellation in circulation during the 1930s was the Style Moderne. Interestingly this phrase has almost never been used by the architects in Bombay. The phrase, such as it is, is invoked only by a journalist, Kanhaiyalal Vakil, in a stringent critique of the buildings of the day. Most architects refer to the buildings of their time as Claude Batley does, calling it ‘this New Architecture’, or ‘modern architecture’ or merely ‘architecture’. This is not due to ignorance, as has already been shown. Rather, the need not to name or label is an indication of contemporaneity, of an attitude of living in the present, of indulging in the exuberance and joie-de-vivre of the time as expressed the state of the art in architectural and constructional development. Claude Batley would coin another term- ‘nationalist architecture’ that gained limited currency as architects sought “a special architectural sensibility and aesthetics which would match and give concrete expression to political freedom”. (Dossal, 2010, p. 184)

Consider the architecture described in a Presidential Address of the IIA in 1931. The president, Burjor S. J. Aga, was gratified to note that the Bombay public was gradually cultivating a good taste for the much-neglected ‘Indian style’ of architecture – “… the new buildings put up on Bhendi Bazar and Sydenham Road furnish a proof of that growth, which deserves our appreciation and encouragement. Simplicity of style has been taking the place of unnecessarily rich and expensive detail…” (Aga, 1931).

The buildings Aga refers to as the ‘Indian style’ are actually buildings in the ‘Art Deco’ style (Figure 5). Aga here, inadvertently, defines an entirely separate practice of architecture, parallel to that of the imperial projects, but carried out by natives, albeit professionally trained, who referred to themselves as Indian, as opposed to British/ Imperial (Dalvi, 2004, p. 45).

Conclusion

The changed Bombay of the 30s and 40s exuded an attitude of optimism, of looking to the future. Batley looked back at the past with some pride, as he contemplated the present: “It is a history of which no city in the world need be ashamed in having accomplished during less than 100 years and if mistakes have been made, they were the mistakes of optimism, progress and initiative rather than of inaction and cowardice.” (Batley, 1934, p. 11). Architecture in India, insisted Batley, freely borrowed from the east and the west due to trade and other influences in the past: “In the chief cities, at any rate, it is inevitable that her modern architecture will be influenced by the world movement that has now made architecture almost international and that only her climate, of which by the way she has almost every variety, will continue to mould these foreign forms into new shapes to meet the extremes of her tropical suns and monsoon rains.” (Batley, 1935, p. 118).

In the wake of the crudity of the Industrial Revolution, Batley regretted that architects in England fell back upon the revivals out of sentimentality and this choice was superficial and transitory. Despite this, Batley has been described as a ‘neo-traditionalist’ by writers commenting on his practice and his writing, such as Lang, Desai, & Desai (1997, p. 141). Batley believed in an ‘Indian’ architecture that emerged from the climate and environment of the Local, not reliant on the superficial symbolism or the hoary forms of the past, but created of modernist choice making, adapted to the local conditions. It naturally follows that Indian architecture should “join a world movement towards a saner building phase; in doing so however she should not lose the sight of the vital facts of life in India, by the observance of which the old Indian designers achieved results that were brimful of ‘thinking and feeling’.” (Batley, 1946, p. 22).

Batley’s ‘This New Architecture’ in Bombay paralleled ‘Deco’ elsewhere in Europe in its outward trappings, in its stark geometries, its ornaments in relief and its espousal of the new materials of the day, but its attitude is sublimated in the Local, its intention to create a habitable city and give comfort to its residents. Claude Batley’s writings, pedagogy and initiatives in documentation have yet to be reconciled with his prolific practice. His influence has been frequently mentioned but only sporadically gone into and deserves a much more detailed research appreciation.

Recent writings as mentioned earlier, have described the architecture of pre-independence Bombay as decorative (hence pre-modern), derivative (Western), formulaic, fusion-traditionalist (motif-based), alien (ignorant of local conditions), facile (thanks to the Hollywood/ cinema connection) and part of the colonial agenda (Dalvi, 2004, p. 44). However, as has been seen in the paper, contemporary voices completely belie these assumptions. Architects, users and commentators at large were aware of the past, and yet they, in the wisdom available to them two decades before the Nation State, with the knowledge of what was imminent, chose to align themselves with an International future.

Ultimately, the buildings speak for themselves. They have weathered well into the second decade of the new millennium, seventy or eighty years after they were contemplated, built and commented upon. They knit together the emerging urban fabric of a commerce driven metropolis and stand symbolic of its global aspirations and cosmopolitan culture. At the same time, they address the context of the region critically, not so much from a cultural but an environmental standpoint. For the city of Bombay and by extension- the prospective free India, these buildings signify Modernism and stand as the vanguard of a peoples’ larger future.

Acknowledgements

A version of this paper was previously presented at the Seminar: ‘Architecture as Social History: Reflections on Bombay/Mumbai’, organised by the K. R. Cama Oriental Institute, Mumbai on 23-24 January 2010, under the title, ‘‘This New Architecture’: contemporary voices in Bombay’s architectural development in the 1930s’.

Notes

1 This paper deals with a period of 1930s and 1940s and retains the contemporary name of the city – Bombay. The city was renamed as Mumbai in 1995.

Dr. Mustansir Dalvi is Professor of Architecture at Sir JJ College of Architecture, Mumbai. He has lectured, read and published several papers and books on architectural history and heritage. He is particularly interested in the development of Indian Modernism in the early 20th century, seen through its expressions in the architecture of the time. In his doctoral research completed at the IIT-Bombay (IDC), he has charted a semiotic of Bombay’s Art Deco Architecture.

This article has been reproduced with permission from the author. It originally appeared in the Tekton Journal Volume 5 Issue 1, March 2018 pp. 56-73.