Until just a century ago, the bathroom, a part of the home often taken for granted, was a novel emergence that marked a monumental shift in modern life. The amenities, comforts and convenience of the modern bathroom revolutionised the act of bathing, introducing for the first time concepts like running hot water, overhead showers, the bathtub and even the flushing toilet. Barring a few refinements over the decades, the basic framework of the bathroom as we know it today remains close to the unprecedented advancements made in this space in the 19th century, when indoor plumbing first began. This modern amenity, however, has for long been entangled with questions of hygiene, privacy and aspirations. An interesting site to observe its emergence, and place within the home, is the history of modern Bombay. With its complex convergence of commerce, migration and land reclaimed from the sea, the city perfectly demonstrates the significance of sanitation.

Bombay grew out of a group of seven islands merged to form a single landmass in the 1800s, and by the 20th century, it had become the veritable economic hub of the East. Prompted by this historic land reclamation, it drew migrant workers, professionals and expatriates alike from several parts of the world. There was, therefore, a pressing need for urban transformations that would accommodate this influx of people, a crucial element of which was the appearance of the self-contained flats. These were living spaces which, as historian Nikhil Rao says, were “an economic compromise between the cottage and the tenement”, frequently attracting the emerging middle-class in the city.[1]

The descriptor “self-contained” refers to the pivotal fact that the toilets were attached to the dwelling, in sharp contrast to chawls, which had toilets on each floor for communal use.[2] The dwellings in these chawls were typically single-occupancy rooms, accommodating entire families of migrant workers such that the private invariably became the public.

Many of the more socially mobile class of migrants looking to make a life in the city, therefore, flocked to the low-rise apartment blocks being constructed in the city’s suburbs like Dadar-Matunga. Though more expensive than life in the chawls, these complexes offered the luxury of space, ventilation and, most importantly, privacy.[3] The attached toilet of the self-contained flat brought on a new definition of the private, and with it emerged a whole new industry dedicated to toilet fittings. No longer was the toilet just a functional chamber to perform ablutions. It now had attached associations of design, aesthetics and middle-class mobility.[4] It became a signifier of the comforts and luxuries of modern urban living, moving into the boundaries of the home, and becoming a significant aspect of interior decoration and design. A modern city had been reclaimed from the sea in the previous decades, and by the 1930s, it was time to build homes that were suitable for this city.

The Modern Bathroom – A ‘Temple of Beauty’

“A good bathroom is the unmistakable sign of a good home. What is your bathroom like?,” reads an advertisement found in a 1936 issue of the Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects. The advertisement, by the company J.B.Norton & Sons Ltd., makes a case for the bathroom to be “artistic, elegant, and above all things, hygienically modern”.[5]

Where once the bathroom was an external appendage to the home, the self-contained flat not only brought it into the dwelling but also kindled aspirations of modern luxury via what it looked like. The comforts it had to offer became some of the key facets of this aspiration. A Times of India article from 1937, about the Ideal Home Exhibition held in Bombay, illustrates the amount of thought one was expected to put into the “ideal” bathroom. The entrance of coloured tiles and vibrant paints into the market, by that time, had opened up possibilities of interior design when it came to the lavatory. Earlier styles of all-white walls and floors were being traded in for coloured accents, from tiles to paints and fittings. But even in this transition, there was care taken to ensure the materials used in the tiles and sanitary ware were visually compatible, as they “do not reflect light to the same extent”.[6]

Arguing in favour of colour, the article read: “This dead white may be the apotheosis of cleanliness but in a land where glare is the order of the day for many months in the year, something more restful is demanded by busy people who snatch with their baths a few moments of recuperation from the daily round.”[7] Notably, there emerges a clear understanding of the bathroom as a place to unwind. If bathing remains a sacred ritual in Hinduism, with tenacious connotations of “purity”, the modern bathroom gradually stripped the sacred away, fashioning itself as a place for everyday moments of leisure and recreation.[8] Another Times of India article from 1934 declares that “bathrooms are becoming Temples of Beauty”. Describing various styles suitable for modern homes, an interesting entry is that of the “Author’s Bathroom”, featuring a “head rest with rubber cushion and writing desk on special rack”, to be fitted across the bath.[9] This chamber, then, even becomes a quiet haven for intellectual stimulation.

‘We Are All Knights of the Bath’

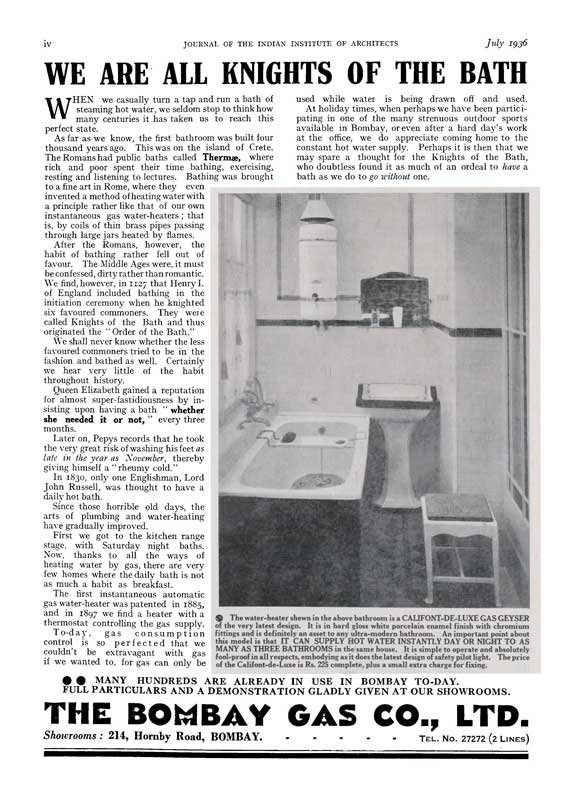

An important aspect of the modern bathroom taking on this quality of leisure and comfort is the availability of hot water on demand. Earlier, procuring hot water for bathing meant making arrangements or bandobast in advance, as a 1929 Times of India entry lamented about the bother of “ordering a bath”.[10] This involved “heating the water over a coal or wood fire somewhere in the servant’s quarters”, then “having the water conveyed to the extreme end of a big bungalow”.[11] With the arrival of electric and gas heaters, however, water would gush out hot from the tap – a novel development so easily taken for granted today. A 1936 advertisement by Bombay Gas Company illustrates an evocative picture of life before instant hot water. Titled ‘We Are All Knights of the Bath’, the advertisement claims that the habit of bathing “fell out of favour” in the Middle Ages, though in 1127, King Henry I did mandate ritual bathing for knighting commoners in England.[12] Only a few centuries later, another monarch of England, Queen Elizabeth I, reportedly bathed once a month “whether she needed it or not”, states the advertisement.[13]

The veracity of this quote often attributed to Elizabeth I remains contested, as do the claims about hygiene practices in mediaeval Europe. There is evidence to suggest washing up and laundering of linen undergarments was a regular affair, even if bathing was not. Having said that, running water was the preserve of the elite, and without easily accessible hot water, bathing in the testing winters of Europe would have been no mean feat.[14]

“Spare a thought for the Knights of the Bath, who doubtless found it as much of an ordeal to have a bath as we do to go without one,” appeals the advertisement.

Interestingly, it is relations with Indian women that encouraged the British officers of the Raj to partake in regular bathing, evidenced by the word “shampoo” – derived from the Hindi word “champi” or head massage – entering the English lexicon around the same time.[15]

It is also women who, as scholar Abigail McGowan has pointed out, often became the target audience for interior decoration advertisements, and bathrooms were no different.[16] This section of advertising tapped directly into the aspiration of what modern life should look like. A clean, well-designed and laid out bathroom became a marker that the owner was clued into international styles and trends. Writing in Modern Ideal Homes for India in 1939, architect and social reformist R.S. Deshpande opined that “middle class families have to keep a certain status in society, very often beyond their means. Therefore, a flat designed for such a class of people should appear to be stylish and should show a high order in the workmanship”.[17] A sophisticated bathroom, in other words, became a crucial symbol of one’s social status.

From Privies to Attached Toilets

The story of how the bathroom, combined with the water closet or W.C., made its way into the modern home, however, is not a straightforward one. Before the arrival of indoor plumbing and flushing toilets to the subcontinent, it was not uncommon for human excreta to be disposed of manually (a practice that continues in some form, in several parts of the country). For upper-caste Hindus, notions of hygiene also extended to ideas of “purity” and “pollution”, and bodily waste was looked upon as ritually impure. It would, therefore, be the job of someone lower in the caste hierarchy to handle the waste, somewhere away from the living quarters. The emergence of indoor plumbing certainly made it possible for the self-contained flat to develop by the 1920s, but bringing the toilet into the interiors of the home was not necessarily the natural trajectory. After centuries of using privies or outdoor toilets, the act of relieving oneself inside the confines of the home, even if the modern flushing technology made it the more convenient alternative, marked a monumental shift in caste practices.

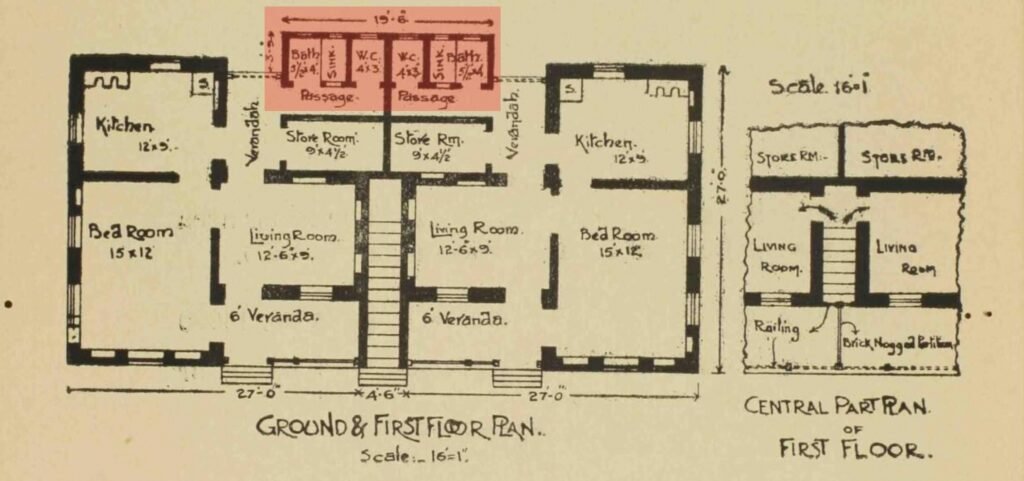

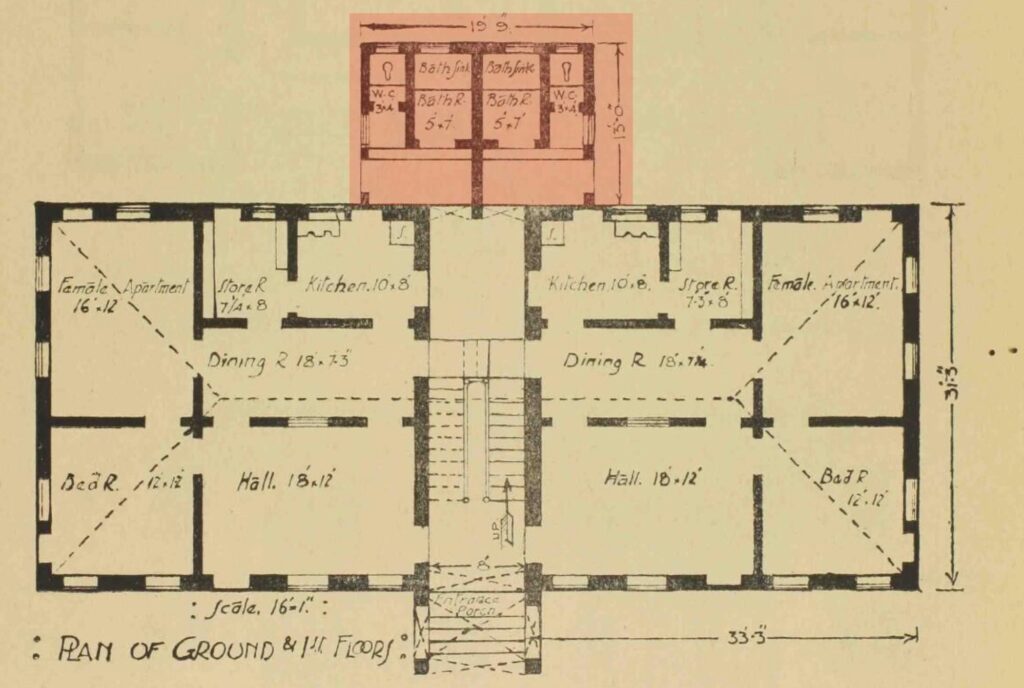

Since the flat was advertised as “self-contained”, the toilet could not be placed anywhere outside the house. Floor maps of the early self-contained flats, however, show that the bathroom and toilet block was relegated to the back of the house, separated from the main living quarters by a narrow passage or a verandah. In Deshpande’s 1931 book, Residential Buildings Suited to India, he recommended that the “W.C’s etc must be far removed from the kitchen and dining room, and so on”.[18]

At the end of the decade, when he wrote Modern Ideal Homes For India, an update on his previous tome, the toilet block seems to have entered the home. “Still, they should be separated from the adjoining rooms by means of a small lobby or at least a blind wall,” Deshpande adds.[19] In the intervening years between his two books, the bathing block becomes more firmly integrated within the living space.

Civic activist Nayana Kathpalia recalls finding the original floor plan of her apartment from the late 1930s, in the row of Art Deco buildings in south Mumbai’s Oval precinct, “very strange”.[20] “We had attached bathrooms with the bedrooms, but the bathrooms did not have a toilet, because you know, it’s this peculiar, I think, Indian-Hindu concept [sic], of keeping the toilet away from the bath area, so whoever comes to clean it …” she trails off.

It was only after her family moved into the apartment that toilets were installed in every bathroom, a practice she says other tenants of the building gradually also followed. “Otherwise there were two toilets in the middle of the corridor, in the middle of the house, we really found it very strange,” she recounts.

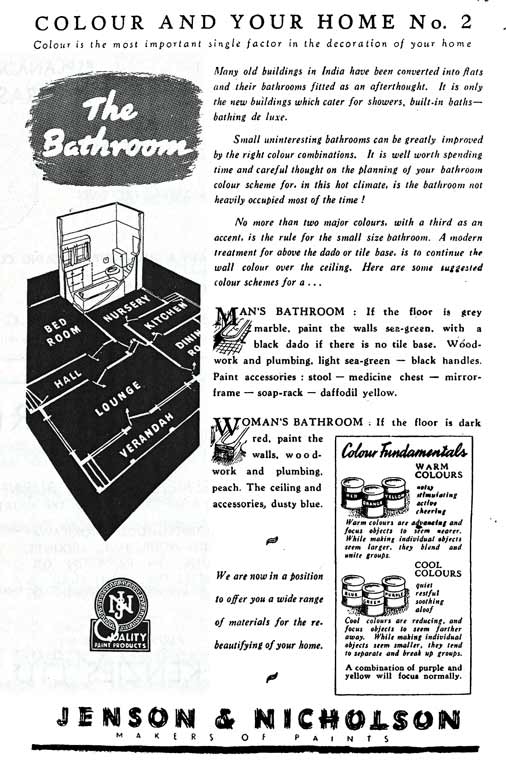

By 1946, an advertisement for the paint company Jenson & Nicholson showed the bathroom attached to the bedroom, complete with a W.C, bathtub and vanity. “Many old buildings in India have been converted into flats and their bathrooms fitted as an afterthought,” reads the copy, hinting at its gradual journey into the interiors of the home.

Purity vs Hygiene – a Middle-Class Discourse

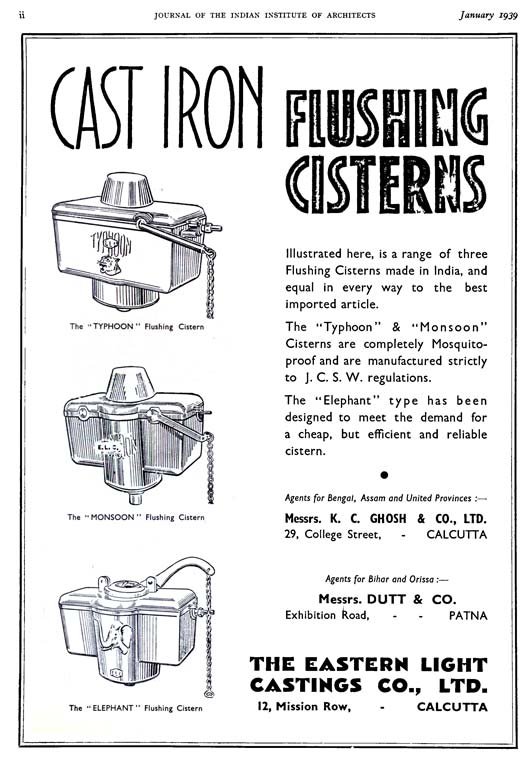

As indoor plumbing and efficient drainage (at least in big metropolises like Bombay) replaced the need for manual scavenging, the association of bodily waste with caste-based ideas of purity and pollution gradually shifted, becoming more tied with questions of public sanitation.[21] The city’s recent history with an epidemic, the experience of which prompted the construction of new apartment blocks in order to decongest living spaces, also engendered a discourse on public health.[22] It was not uncommon to see companies advertising “mosquito-proof” flushing cisterns at this time. Several of these companies also described themselves as “Sanitary Engineers”.

This shift in discourse from “purity” to one of public health is closely associated with the emergence of a self-conscious middle-class – an educated class of professionals, seemingly more engaged with urban issues of hygiene than with archaic caste practices.[23] Still, the complexity of the caste problem does not go away but often manifests in different ways. Noted writer and journalist Shanta Gokhale describes the flats in Shivaji Park in suburban Dadar where she grew up, as having two entrances to the toilet block – one for general use, one attached to a “separate spiral staircase at the back of the building”, for the sweeper to clean it without entering through the house.[24]

This is corroborated by Deshpande’s instructions in Modern Ideal Homes, where he describes the service entrance thus: “There should be preferably another staircase at the rear for servants, and this should be independent for each flat de luxe, since much annoyance is likely to be caused if servants of two flats on the same floor meet on the common staircase and converse with each other at the sacrifice of work.” [25]

Even with all its contradictions, however, apartment living did bring about a way of life that marked a shift into a modern epoch. Not only was it hitherto unimaginable that the toilet would be attached to areas of the house where one eats and sleeps, but the compulsions of modern, urban living also meant people often lived next door to those of different faiths, nationalities and beliefs, even if they were of the same class.

These apartment blocks brought into the city white-collar migrants of diverse backgrounds, who nonetheless came together to adopt common ways of living, by virtue of how the flats were laid out.

Most importantly, these apartments set some of the earliest precedents for modern ways of life. While access to clean toilets and privacy continues to be a matter of concern for many in India, it is with the self-contained flat that the imagination of such comfort began, even for middle-class people of limited means. To date, a home with a bathroom attached is a prominent marker of middle-classness and social stature in India.[26] We need not all be ‘Knights of the Bath’ to appreciate the comforts of the modern bathroom, a breakthrough of just over a century ago. With every turn of a faucet of hot water and a flushing toilet, there is the long and complicated journey of the bathroom’s emergence in our lives, and its contentious entry into the boundaries of India’s modern homes.

* Bombay was officially renamed Mumbai in 1995. Wherever the article describes events before 1995, the city is referred to by its former name.

Suhasini Krishnan for Art Deco Mumbai

Suhasini is a writer and journalist based in New Delhi, with an academic background in Film Studies and History. Her research interests lie in cinema, modernity, and the making of an urban city.

Header Image: Digital illustration for Art Deco Mumbai by Urvi Khadakban.