In 1858, the East India Company officially extended its mission from trading to colonising the Indian subcontinent, as a result of which the British implemented direct and indirect rule in the region.[1] An area under direct rule would be controlled entirely by the British, which included departments like education, health, judiciary, municipality, and police, to name a few. The provinces, comprising areas ruled by the Maharajas, noblemen and landowners, made up about a third of the subcontinent, and came under indirect rule. These were collectively referred to as the “princely states”.

The Maharajas enjoyed the autonomy of their respective states by paying a subsidy to the British, in exchange for military protection against the competing European colonies such as the French.[2] This arrangement allowed these regions to enjoy a certain degree of freedom in their political and cultural endeavours, often also reflected in their architecture.

The rulers of the princely states, with their wealth and exposure to international styles and trends, played a key role in giving an impetus to avant garde expressions of art and architecture back home, one of which resulted in the emergence and evolution of the Art Deco style in British India, particularly in Bombay.

The Winds of Change

To facilitate better cooperation in governance and trading responsibilities in the empire, the British Raj established institutions for the education of Indian princes based on public schools in England. These schools taught Queen’s English and had a western curriculum.[3] The increasing linguistic and cultural influence of the British created a growing affinity for the myriad wonders of western culture. The desire of the Indian princes to emulate the British ways of living, from clothing to mannerisms, came naturally as a result of their education.

Historian Angma Dey Jhala, in her work on the princely Indian states, has succinctly expressed how Indians slowly adopted western table manners, spoke the Queen’s English, wore western outfits and played ‘the gentlemanly game’ of cricket.[4] They felt protected and comfortable with the idea of this co-existence. They were able to enjoy all the luxuries of life while not having to constantly preoccupy themselves with military pursuits or even the Indian freedom struggle. Many of them had become successful entrepreneurs and were in business with their British counterparts.

The Bombay Spectacle

The opening up of the Suez Canal in 1869 resulted in increased ease of travel overseas.[5] Bombay gained immense importance as the trading and port city connecting the East to the West. It opened up several avenues of economic, cultural and social reform in the Indian subcontinent, due to its strategic location. The Indian elites and princes made use of this development, travelling abroad for education and luxury vacations, and bringing back with them a distinct flavour of Western culture. They were enamoured by the international movements in arts and culture, and also appreciated its finer nuances. They studied at schools such as the Cheam School in Charterhouse, Christ Church College in Oxford and London School of Secretaries.[6]

The growing familiarity with the English language allowed for the momentary dissolution of boundaries when exchanging ideas. As historian Amin Jaffer has documented, “The Maharaja class were becoming good clients of firms such as Cartier, Boucheron, Chaumet, Mauboussin, Garrard & Co., Louis Vuitton, Hermès, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Armstrong Whitworth & Co, Alfred Dunhill, Holland & Holland etc. and in the course of this they naturally adopted the Art Deco style and brought it back with them to India.’’ [7] Travel also increased tremendously between the two world wars, causing the princes to visit Bombay frequently for business, shopping, sports and to participate in the Chamber of Princes, the official collective made for negotiations with the Government.[8]

Bombay had a distinct identity as a global commerce and trade centre, and it was on the shore of this city that modernity first arrived in the subcontinent. Its role from being a fort city to becoming a neo-gothic trade capital, and eventually introducing the British Indian empire to the emergence of a new modern aesthetic, became crucial to the way India embraced modernity.

At the time, Bombay was dominated by industrial elites who were united in their pursuit of financial prosperity. The city, as a result, did not have a uniform socio-cultural makeup. It was diverse and cosmopolitan. The collective capitalist aspirations allowed for, to some degree, the suspension of social discriminators like race, religion, caste and creed.

The royalty could experience a new setting where their lineage did not grant them exclusive privileges. It also created a space where they could enjoy luxury while blending in and avoiding public gaze, unlike their life in the princely cities where they were encumbered with the social mores of being rulers.

The development of Marine Drive in Bombay as the Queen’s necklace in the 1930s opened up new avenues of luxurious living. It bore a striking resemblance to the French Riviera, with the city becoming a thriving art and cultural hub. The wide streets along the promenade prompted the arrival of the automobile revolution in the city, and by 1920 most automobile companies like General Motors, Ford and Premier Automobiles had set up shops all over Bombay. Cars like Buick and Chevrolet were assembled and sold here. Exclusive showrooms like the French Motor Car Co., Dadajee Dhackjee and Co, and the Automobile Co. Ltd sold the latest designs in Deco cars.[9] However, the high-end cars owned by most of the Maharajas were often custom-designed and assembled in the United States of America or Europe, sometimes taking a year to finish and ship to India.[10]

The apartment-style residences in Bombay were planned with garages on the ground floor, signalling for cars to be the next attainable item of luxury. With the ease of travel, the city saw the emergence of international trends simultaneously with the West. The development by the waterfront in Bombay, the low-rise apartments with a uniform visual aesthetic affording beautiful views of the sea, and the esplanade on the other side, had all become the poster vision of urbanity in India.

The royalty was seduced by the glamour of the flourishing city, with its wealthy merchant class defining a new lifestyle through the latest automobiles, cinema theatres, sports clubs and an emerging international culture of consumption in the modern metropolis. The perks of this urban lifestyle, coupled with endless economic opportunities, attracted one and all to the spectacle that was Bombay.

The Indian “Lord’s”

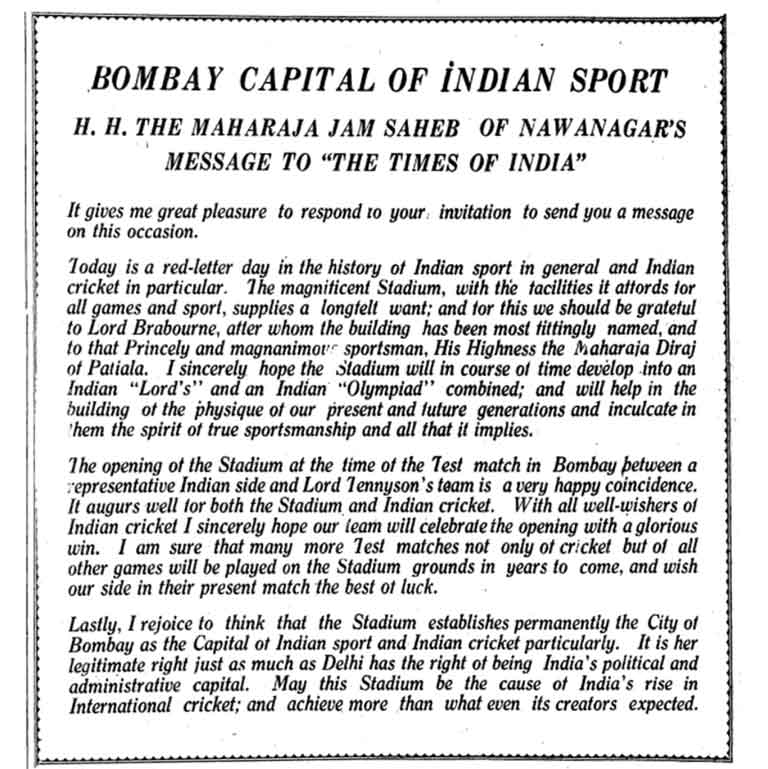

The astounding financial progress of the merchant class in Bombay, predominantly led by the Parsis, resulted in the development of several public buildings for recreation, the Gymkhanas being one of them. These gymkhanas gave the Indian upper-class access to quality sporting facilities. Sports clubs became an indispensable part of the modern urban lifestyle. Their popularity, and the increasing presence of the princes in the city, culminated in the development of a giant sports complex in the south of Bombay, known as the Brabourne Stadium.

In the 1930s, several building schemes were developed on the reclaimed land to the south of the town, and a massive site was reserved at the edge of the sea for this iconic sports complex. The Cricket Club of India intended for this to be India’s version of the “Lord’s’’.[11] Cricket had fast become a passionate preoccupation of the princely class and the British. The Maharajas had taken to the sport quite readily and indulged in the idea of socialising with the British and establishing a camaraderie outside of official work.

It was not surprising, therefore, that several donations were made by the Maharajas and the business entrepreneurs of Bombay, for the construction of the stadium. This new development prompted members of the princely states to visit Bombay even more frequently.

Palaces of the New Order

Earlier, the Maharajas rented villas and luxurious apartments or stayed in hotels in the newly developed Art Deco precinct. Post the 1930s, with increasing interest in the city, they quickly started building their own mansions or apartment blocks in Bombay. The Maharajas of princely states such as Bansda, Baroda, Gwalior, Hyderabad, Bikaner, Kutch, Rewa and Wankaner, all built palatial villas in Bombay. There were approximately 40 palaces built in the city at this time,[12] concentrated on the West side of the island, below Cumbala and Malabar Hills, and in the area bordering Warden Road and Nepean Sea Road.[13] While back home they established sovereignty by building monumental edifices for their residences, in Bombay they chose to blend in with the wealthy upper class by adopting the Deco style.

The Art Deco style embodied visual renaissance, celebrating the new age and beckoning a change in the world order. It provided an appropriate expression that was modern, yet was flexible for interpretation. As a response to urban living which allowed for innovations in building form and urban morphology, it even introduced new possibilities in lifestyle. The royals felt it was an appropriate modern expression reflecting their changing sensibilities and refined taste. Some of them even commissioned palaces in this style in their regional centres. These mahals or palaces were built using the Deco language but were skillfully customised to incorporate traditional motifs and features reflecting a local cultural identity. Some other Maharajas, such as the Maharaja of Baroda, asked his architect to design a gymkhana in his princely state in the Deco style.[14] This new architectural style was seen as an appropriate expression reflecting their progressive and cosmopolitan outlook.

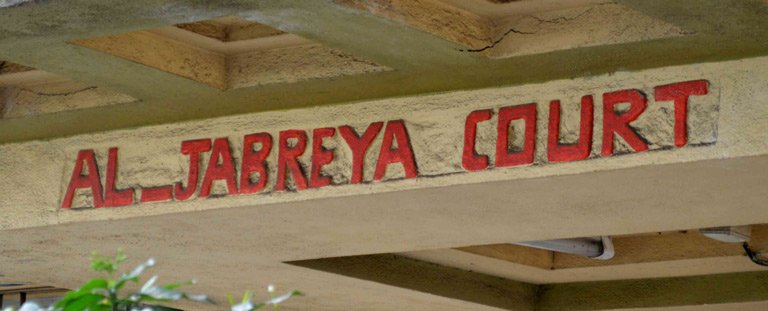

Soon, Bombay’s popularity also garnered the interest of the royals and the wealthy class from neighbouring lands, who were eager to establish their presence in the city. The Emir of Kuwait purchasing two apartment blocks, the Al-Sabah Court and Al-Jabreya Court in the Marine Drive Deco precinct, was a prominent indicator of this convention.[15]

Royal Patronage

The Modern Palace of Indore

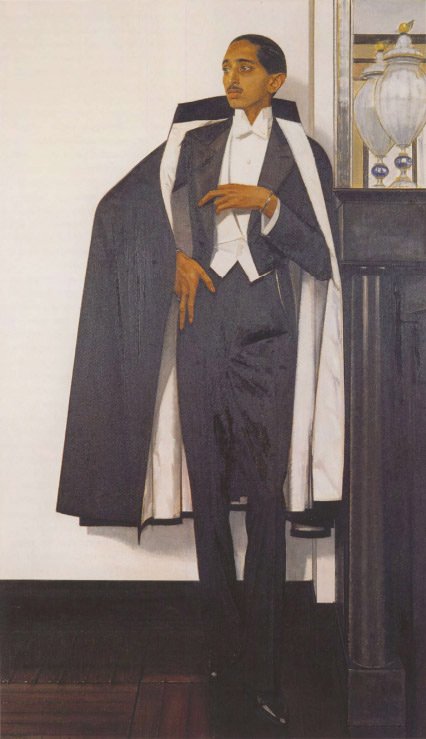

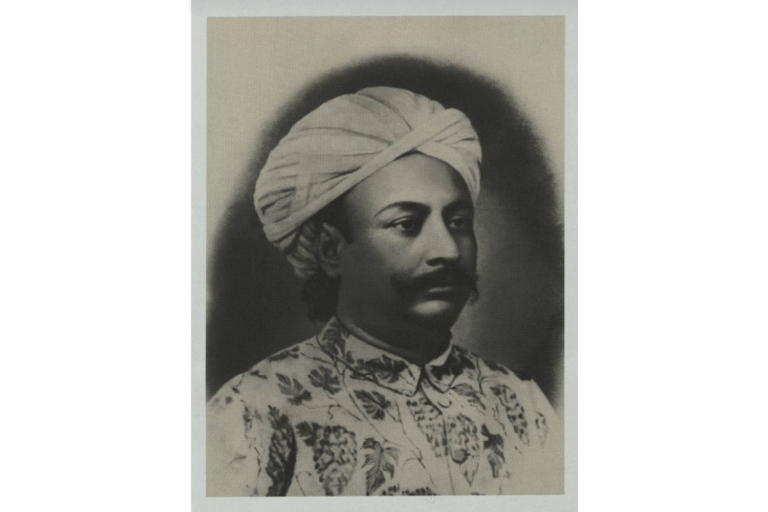

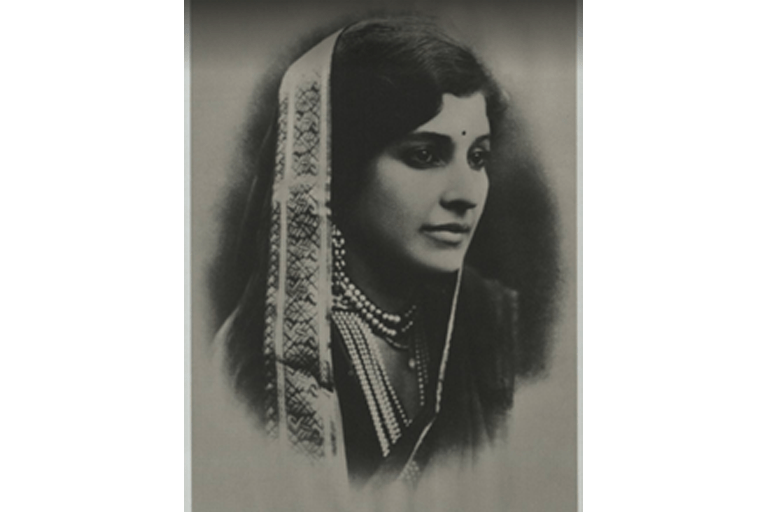

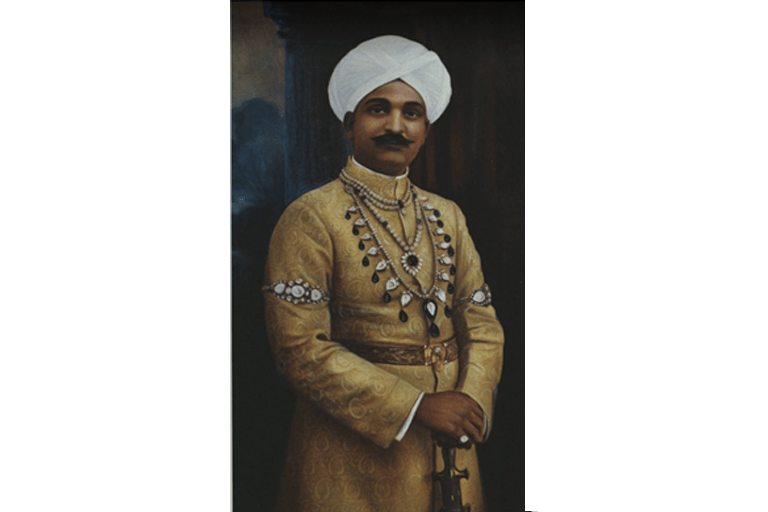

Yeshwant Rao Holkar II, the Maharajah of Indore, was one of the early patrons of the Art Deco style. In 1930, he commissioned his friend, German architect Eckhart Muthesius, to design a modern palace for him and his wife in their princely state of Indore, called the Manik Bagh or the Garden of Rubies.[16] This development garnered attention in the princely circles and slowly initiated a streak of royal patronage for the Indo Deco style (a careful synthesis of traditional Indian architecture and Art Deco). It was during his studies at Oxford that the prince first met Muthesius.

This meeting, like many others, was arranged by Holkar’s secretary Dr Marcel Hardy, to broaden his understanding of the International Modern Movement[17]. He helped acquaint the prince with international curators and artists such as Henri-Pierre Roché, Picasso, Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp. It was Constantin Brancusi Roché, in particular, who played a pivotal role by introducing several artists to Holkar II, helping hone his taste in art, eventually resulting in the commissioning of Manik Bagh.[18]

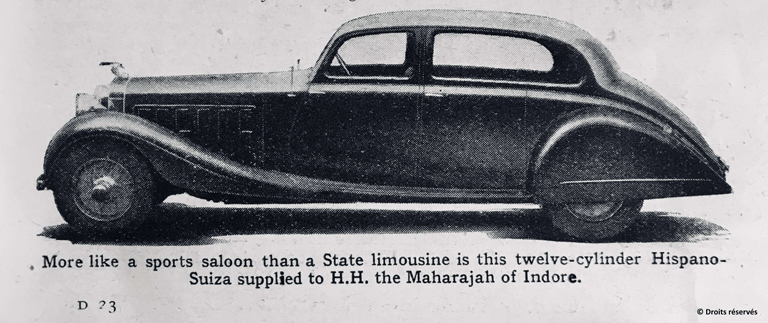

Muthesius designed the interiors of the palace in his factory in Germany, where he also exhibited the designs before shipping them to Indore. He procured several furniture pieces by avant-garde modern designers such as “Le Corbusier, Charlotte Perriand, Eileen Gray, Marcel Breuer, and Lilly Reich, along with some of the protagonists of the so-called French Moderne, like René Herbst, Louis Sognot & Charlotte Alix, and Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann.’’[19] The prince also actively purchased and commissioned custom-made Deco designed cars, such as two similar streamlined limousines by coachbuilder Gurney Nutting – one on a Rolls-Royce chassis and one on a Hispano Suiza chassis, both 12-cylinder cars. Other notable cars he owned were the supercharged Duesenberg, a Bentley 3.5 litre, and a Lagonda V12 – all drophead coupés.[20] Holkar’s early patronage of the design style became a talking point and inspired other princes to quickly follow suit.

Majestic Mansions of Modern Bombay

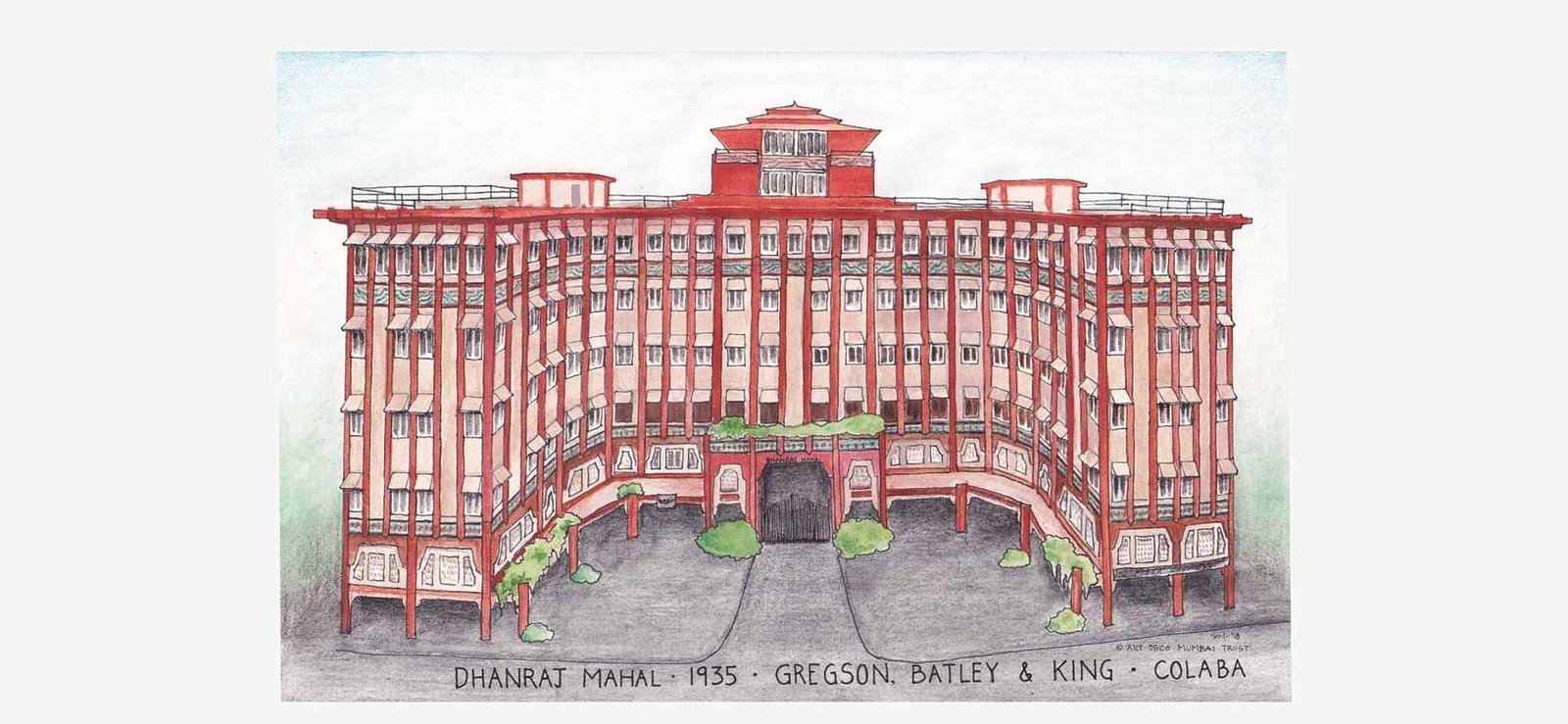

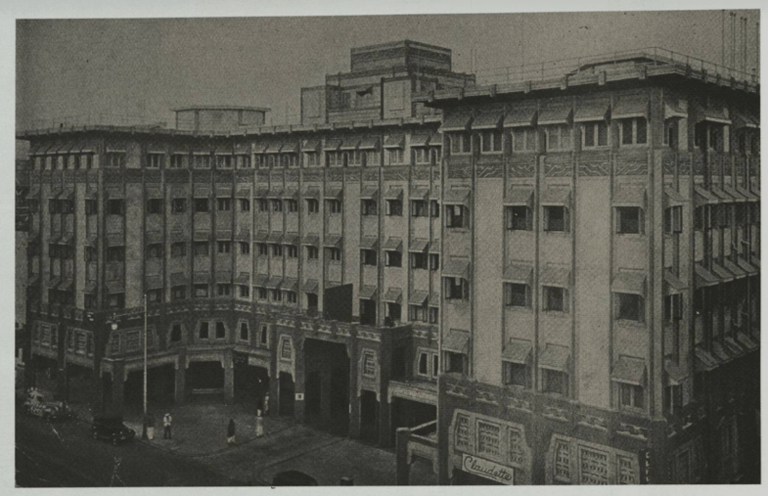

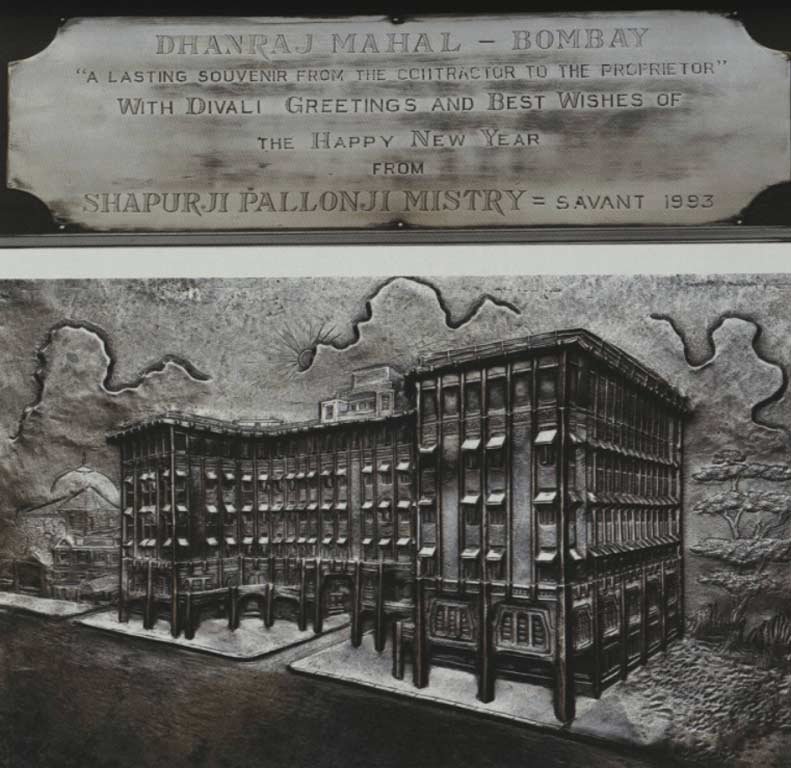

A grandiose princely residence designed in Bombay, called the Dhanraj Mahal, was a landmark development amongst the Deco-style palaces in the city. Situated on Pier Road (now Chhatrapati Shivaji Marg), Dhanraj Mahal was commissioned by Raja Dhanrajgir Narsingir Bahadur of Hyderabad, and was formerly called Narsingir Mansion, after the man whose wealth funded this iconic structure.[21]

Raja Narsingir Gyangir Bahadur, known as the “Rockefeller of the South,” was famous for his astute business sense and financial prowess.[22] This Mahal was built on the former site of the Watson’s Hotel annexe, bought by Raja Narsingir in 1812. Recognising the prime location of the property, his successor Raja Dhanrajgir promptly decided to knock down the hotel annexe in 1932 and build a grand modern structure in its place.[23]

The Watson’s Hotel itself was an iconic symbol in Bombay, heralding a new status of hospitality in the East. A newspaper article dedicated to the construction of Dhanraj Mahal said: “This new “Dhanraj Mahal’’ replaces the building long known as “Watson’s Annexe’’. That fact alone registers a great change. It signifies the passing of an old era and of structures that were destined to give place sooner or later to buildings designed and constructed with the closest adaptation to the requirements of the day.’’ [24]

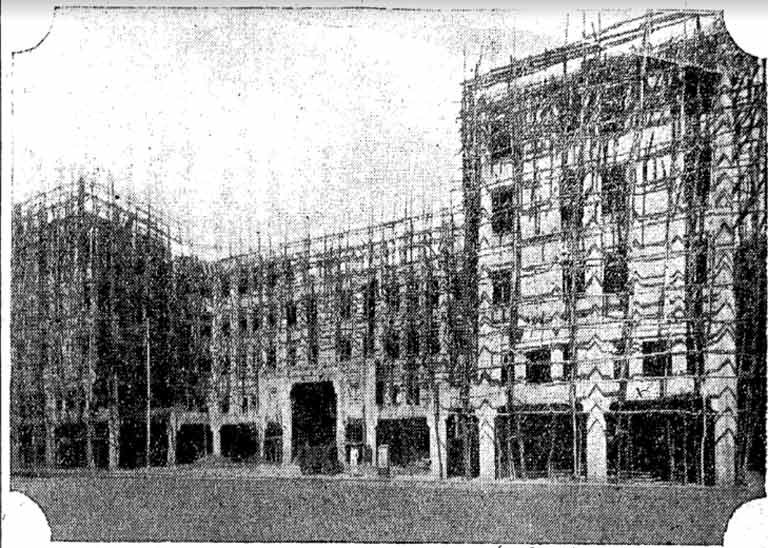

Dhanraj Mahal was the largest architectural commission in Bombay at the time, entrusted to the reputed architectural firm of Gregson, Batley and King, and subsequently modified jointly with Shapoorji Chandabhoy and Co. Constructed by contractors Shapoorji Pallonji and Co, it was notable for its scale and was extensively covered by the Times of India, both during and after construction.[25]

The site measured 1.65 acres, and the building was a mixed-use residential complex with shops, restaurants, offices on the ground floor and residences above. Spacious apartment-style residences with five storeys were planned in seven blocks. The complex had a tennis court inside, and 24 garages on the ground floor on the west side, many of which were used for Raja Dhanrajgir’s fleet of luxury cars, including a Daimler limousine and a rare Simson Supra. [26]

The building was estimated to cost about 14 lakhs which extended to 24 lakhs after completion. All the suppliers advertised prominently, alongside the newspaper coverage about the palace – be it Siemens Schuckert announcing that there were “over three hundred ceiling fans installed” or Bharat Tiles claiming it to be “the largest tiling contract ever given in India!” with “as much as 1860 sq m.” [27] The building has eight elevators, of which one was exclusively reserved for the Maharaja to access his residence on the top floor, which was a sprawling 3,700 square metre apartment spread across the footprint of the seven blocks. The Maharaja’s bedroom was the only private residence in the city that got picture frame views of the Gateway of India. [28]

The Seafront Palace

Another palace of significance built in Bombay at the time was Dariya Mahal, on Nepean Sea Road (now known as L Jagmohandas Marg). It was built for the Maharao of Kutch, who owned a parcel of land measuring 7.65 acres extending from the road down to the sea. He was also known to be a patron of German Mercedes Benz cars and owned a large fleet of them.[29] The palace was carefully planned and executed over five years, overcoming challenging site conditions and technical requirements.

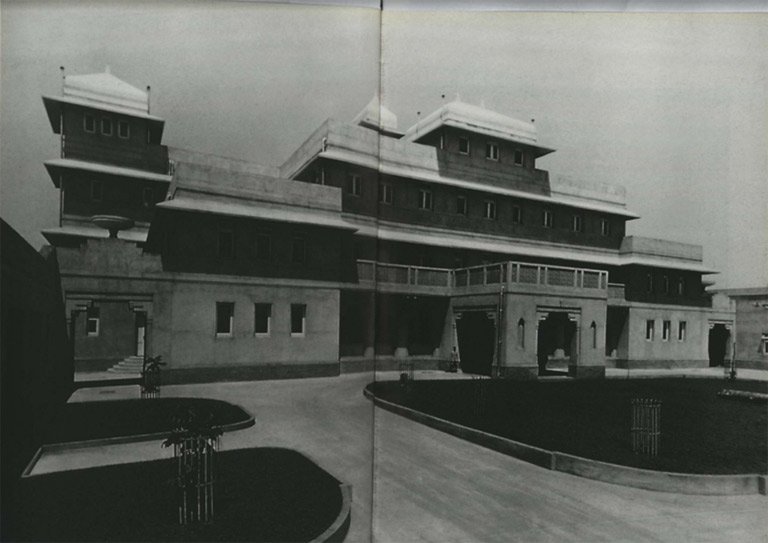

Designed by architects Bhedwar and Bhedwar, and constructed by contractors Mahomed Bawla, Dariya Mahal has a basement, a ground and two upper floors. The larger aesthetical schema carefully borrows from the visual appeal of traditional palaces and fuses it with what is essentially a modern regal residence.

As described in a May 1940 article in Times of India, “The style which is appropriate for an edifice of the Durbar order, is an adaptation of the traditional Indian architecture exemplified by the old palaces of Gujarat and Kathiawar. It seems a very good example of a new building exhibiting the characteristic features of the old works while conforming to the requirements of time and change”. [30]

The design uses architectural features such as Indian motifs, jaalis, domes and traditional Malad stone masonry, within the framework of a reinforced concrete structure. On the façade, one can see the symbols representing the Kutch coat of arms. The building has a large central hall on the ground floor, a darbar hall on the first floor and residential apartments in the northern and southern wings. The second floor consists of bedrooms on all corners with loggias on either side, with six columns and domes at each end. The octagonal towers connected by a central bay on either corner of the building are projected out to get the scenic views of the Malabar Hills and sea on the other side. The integration of traditional architectural features into the framework of a city palace was a common practice at the time, notably the peculiar addition of the darbar hall.

The exterior also followed this balance between the past and the present. It maintained the symmetry on either side of a central high point, while also streamlining it to match the Deco vocabulary of the city context. Today, this palace functions as the Walsingham House School.

Some other palaces of note in Bombay were the Wankaner House (Lincoln House) on Warden Road, built for Maharaja Amarsinhji of Wankaner in 1936, and the Bilkha House (now Ram Mahal), built for the Maharaja of Bilkha in 1939. Wankaner House was the first Indo-Deco style palatial residence built in this area. Designed by architect Claude Batley, it cleverly depicts the fusion of Art Deco and Indo Saracenic styles. [31]

The Bilkha House, designed by architect John Mulvaney, also became iconic for its clever conceptualisation of a setback courtyard at the corner, unlike any other Deco structure built at the time.[32] The building was renamed Rafat Mahal after its acquisition by the Nawab of Rampur. The presence of these palaces, in close vicinity of the neo-gothic British monuments, distinctly marked a significant change in the city’s visual landscape.

While the palaces in Bombay followed the now established visual aesthetic in the city, back home, the princes had the freedom to contrast with their regional building vernacular. They often chose to build in the classic Deco style, identifying the globetrotting Maharajas with the cosmopolitan international culture of the Jazz age. [33]

Redefining Luxury – the New Palace in Morvi

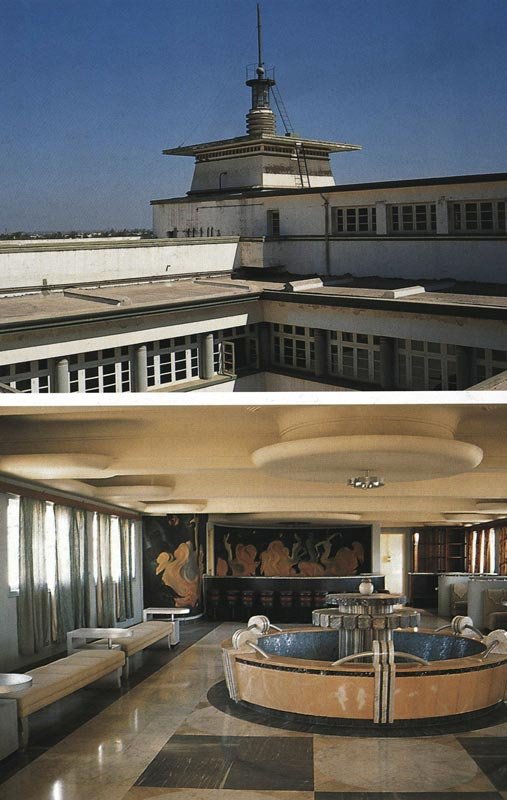

The New Palace in Morvi, built for Maharaja Mahendrasinh Lakhdhirsinh in 1943-44, was a pure Deco indulgence.[34] Situated in a relatively small princely state, in the former Saurashtra region of Gujarat, this palace shows a surprisingly strong influence of the classic Deco style in its art, architecture and interiors. Rajkumari Rukshmani Devi, the daughter of the late Maharaja Mahendrasinh, recalls how the prince, having visited America in his early 20s, was enamoured by the style.[35] Designed by Gregson, Batley and King and executed by contractors Shapoorji Pallonji, the palace occupies only one-tenth of an enormous estate measuring approximately 7,500 sq m. Furnishings for it were shipped from an upmarket interiors firm headquartered on London’s Tottenham Court Road, and Polish artist Stephan Norblin was commissioned to decorate it.[36]

The palace has large living and dining areas, with marble and wood-panelled walls infused with evocative artworks from the artist. The colour scheme, the cylindrical columns, and the motifs used in the furniture, echo the Deco paradigm. The palace’s western influence was not underplayed in any way. It has an indoor pool, a gymnasium and a library reminiscent of English townhouses, complete with walnut wood-panelling and a fireplace. Morvi Palace aptly depicts the lavish lifestyle enjoyed by the royals at the time. Their affinity towards the new style shows their eagerness to break away from tradition and embrace a new cosmopolitan identity and aesthetic.

Maharaja Lakhdhirsinh also owned a vast stretch of property in Bombay, with the Hashmet Mahal in Juhu and a few other apartments in the area.[37] In 1920, he also bought the Watson’s Hotel from Maharaja Dhanrajgir Narsingir and named it Mahendra Mansions.[38] His royal palace symbolises the epitome of opulence articulated using the Deco style.

Indo Deco Renaissance at the Jodhpur Palace

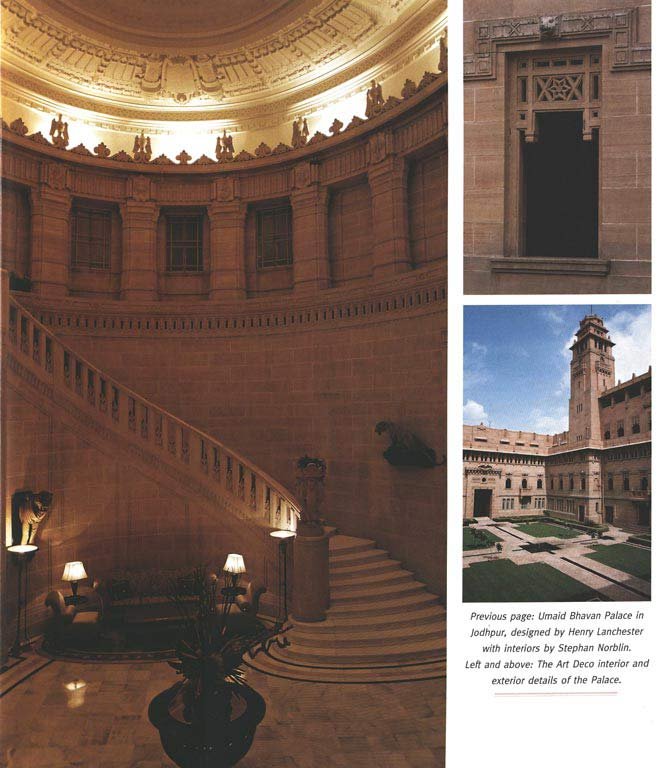

The Umaid Bhawan Palace in Jodhpur, commissioned by Maharaja Umaid Singh, yet another iconic Deco influenced structure, is perhaps the most magnificent palace built at the time. Built to employ his people during a state of famine, the palace was designed by architect Henry Vaughn Lancaster as a perfect confluence of tradition and modernity. Spread over a sprawling property of 26 acres at Chittar Hill in Jodhpur, it was once known as the Chittar palace.[39] The monumental sandstone edifice, primarily influenced by traditional indigenous architecture, also has strong visual references to the Deco style in its interiors. The motifs, sculptural elements, furniture and murals all used minimal, streamlined designs. G.A. Goldstraw, L.F. Roslyn and Stephan Norblin were commissioned to design the sculptures, the artwork and the furniture for the palace.[40]

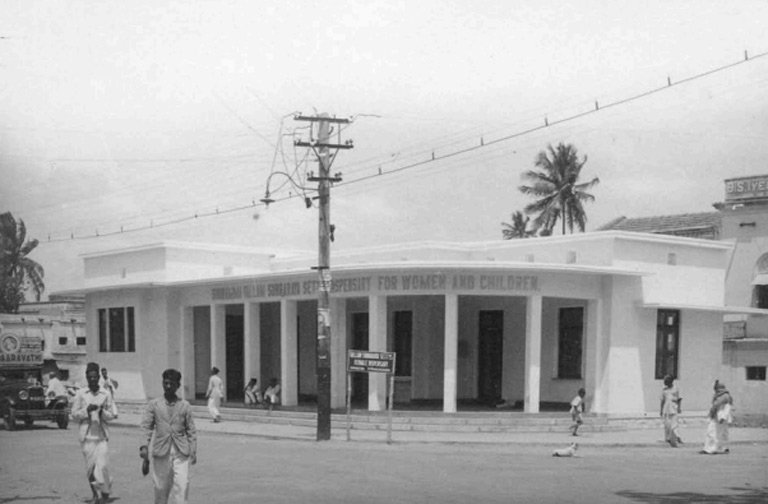

While these are some examples where Art Deco was introduced in the princely states due to royal patronage, there were other princely states such as Mysore, where despite a lack of royal patronage, implementation of the style is evident in several places.[41] Otto Koeningsberger, who was employed as the architect to the princely state of Mysore, was certainly influenced by the Deco style, having studied in the West at the time of its emergence. It is not surprising, therefore, that he chose this expression for the design of a few public buildings where he was not bound by the patron’s directive. The Mysore Engineer’s Association and the Dispensary in Bangalore are two examples of Deco structures designed by him.

Architects and artists who studied in foreign universities, or the ones arriving from the West, witnessed first-hand the revolution brought about by this style in the popular visual culture. They were fascinated by the new possibilities in the material and the formal language, and tried to replicate it in the subcontinent, thereby resulting in a wider reach of the new visual aesthetic.

A New Era

The rulers of the princely states in the Indian subcontinent were the greatest patrons of the Art Deco movement in India. It was a mutually beneficial relationship where the style gave the patrons a chance to redefine themselves, and in return, it flourished significantly with their full-fledged support.

The princely commissions of Art Deco helped find the style its appropriate patronage and popularised it well beyond the shores of Bombay. Through its medium, the best of designers and artists across the world had an interface with the Indian subcontinent, which led to the creation of some significant architectural marvels and a new design idiom in the subcontinent.

As the precursor to Modernism, Art Deco as a style helped familiarise India with the material, formal and technical language of the Modern. In their efforts to modernise themselves, the princely rulers actively created a foundation for the eventual evolution of the modern movement in the Indian subcontinent. Bombay, as the epicentre of trade and commerce, became an eternal muse for the aristocracy. Their desire to ride the tide of change, and mark their presence in the city, found resonance in the novelty and adaptability of the Deco style, which marked a significant shift in the world order. The Deco-style buildings in Bombay underscored the cosmopolitan identity of the city, and in choosing to blend in, the princes validated its significance furthermore. Dotting the skyline of Bombay, their magnificent Deco palaces strengthened the foothold of Art Deco and established a new building vernacular, one that the city enjoys to date.

* Bombay was officially renamed Mumbai in 1995. Wherever the article describes events before 1995, the city is referred to by its former name.

Chaitali Patil for Art Deco Mumbai

Chaitali Patil is an architectural researcher. A graduate of CEPT University, Ahmedabad, she has a particular interest in the development of Modern Architecture in India. In her career, she strives to strike a balance between research and practice.