This essay examines the high level of cultural negotiation that took Bombay by storm in the 1930’s, yielding a string of ‘Bombay Deco’ buildings that boast of classic Deco elements interwoven with strands of the Indian visual tradition. It explores the themes of native stories, religious symbols, mythology and lettering by uncovering the Bombay-ness that underpins the eclecticism of Bombay Deco.

In Rushdie’s 1999 novel, The Ground Beneath Her Feet, the narrator, Rai, confesses that he grew up believing “Art Deco to be the ‘Bombay Style,’ a local invention.” He thought that the name had been derived from dekho, to see—“lo and behold art.”[1] Rai, obviously, was wrong. Art Deco (name coined only in 1967), initially known as Style Moderne, got its name from the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, [2] a world fair held in Paris in the summer of 1925. It was at this Exposition Internationale that Art Deco debuted.

Although Art Deco found its origins in France in the 1920s, it also found a home in Bombay in the 1930s. And although Art Deco had a grand international unveiling at one of the most international events of the time—the Exposition Internationale—it soon accrued a distinctly domestic flavour as the style spread through Bombay. Standard Deco motifs were interlaced with strains of the Indian visual tradition to beget a string of uniquely “Bombay” buildings. These buildings featured hallmark Deco elements such as streamlined design or ziggurats with dashes of Indian cultural markers such as native lettering or religious symbols, among other motifs. Suddenly, Rai’s musings about the origins of Art Deco don’t seem so misguided after all. Indian visual traditions were so comfortably incorporated into the language of Art Deco, that these buildings stand out as a “Bombay Style.” The near homonymy of dekho and Deco coincidentally seems to affirm this.

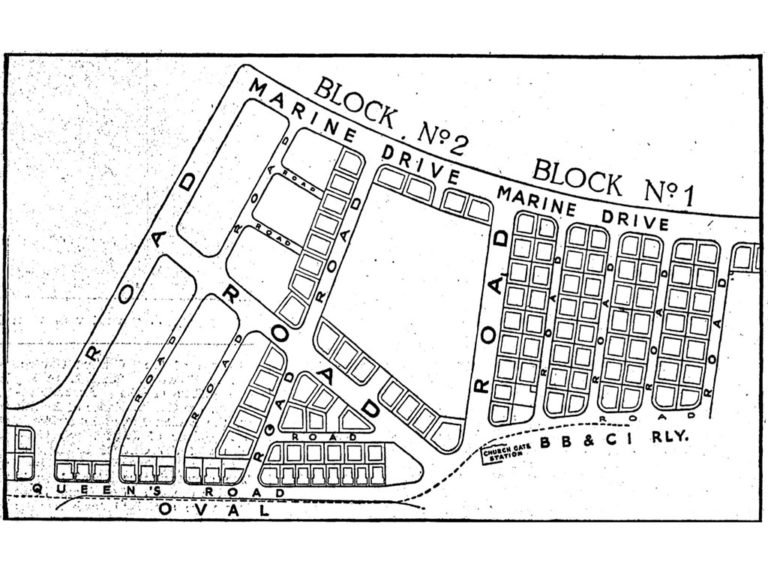

The accumulation of Indian ornamentations in Art Deco, however, was something that happened over time. Deco first emerged in the tony southern tip of the city in conjunction with the development of the Reclamation project that extended from the western edge of Oval Maidan (East) to Marine Drive (West). The style was brought to India by the country’s elite who would travel overseas and return to India hoping to realise the luxury and suave modernity that it stood for. Hence, when Deco first rocked up on Bombay’s shores, it was quite a faithful adoption of the “original Art Deco style” that used “the newly available technology,” [3] namely reinforced concrete. The buildings that cropped up on the western edge of the Oval, after the land had been reclaimed, at large reflected Western aspirations. Apart from a few clever architectural modifications that equipped these buildings for Bombay’s unique weather conditions,[4] buildings along the Oval did little by way of adornments or names to further articulate Indian tradition. Not only were these buildings nearly devoid of distinctly Indian cultural markers, but they also were also quite imperial; Anglophilic even. Buildings such as the Queen’s Court and Empress Court stood on Queen’s Road (now Maharshi Karve Road) facing the Oval, and soon after, another string of buildings on the reclamation formed a coastal promenade we now know as Queen’s Necklace or Marine Drive.

However, the customs of Western nomenclature and staying “consistent to the original style”[5] of Art Deco were soon shed. After the implementation of Art Deco in the Backbay Reclamation project, the style was “co-opted across the city in new developments,” [6] particularly in the suburbs. As the style moved north towards the suburbs, many of the residential buildings were built “in the Deco style” with “traditional details from Indian architecture.” [7]

Soon, the Courts gave way for the Mahals, and an assembly of buildings arose where religious symbols formed a part of the building’s detailing. Kanti Mahal (Matunga), designed by Suvernpatki & Vora, is ensconced in symbols from Hinduism. The outer gates of the building have a set of wrought iron swastikas, lending all entrants a sense of auspiciousness. The entrance canopy of the building has a lotus, associated with Lakshmi and Vishnu (Hindu gods), below the lettering while the pilasters next to the entrance resemble those of a temple. All of this, of course, is integrated into a larger Deco framework of abstract organic forms and highly symmetric and geometric patterns, as is exemplified by the clocktower which is part of the building’s complex.

Another residential mahal, Hira Mahal (Wadala), found its form dictated by Deco, yet its façade adorned by Hindu symbols. Among the wondrous collection of classic Deco features such as dark blue bands and nautically inspired observatory towers, is an Om symbol and two diyas (oil lamps)—all executed in low plaster relief. The Om is at the centre of a red, rising sun which is striking among the sparse blue bands and white plaster. This relief work is auspiciously emblazoned along the street corner façade of the building.

Buildings in the suburbs often had “more constrained budgets” [8] and “were less bombastic than their counterparts in the South.” [9] However, what these buildings lacked in financing, they made up for in more elaborate “experiments with Deco.” [10] As the numerous Deco Sadans, Mahals, and Bhuvans would have us believe, names reminiscent of the Empire were quickly cast away in favour of indigenous names. But, in a step further, some buildings did away entirely with the Latin script and norm of writing even Indian names in English. Instead they reverted to writing building names in Hindi, Gujarati, and Urdu scripts.

Uday Vihar in Dadar is distinctive for the large stained-glass lettering that crowns its otherwise modest entrance. The name, “Uday Vihar,” written with white stained glass and in Hindi arches over “1937,” presumably the year the building was built—this forms the foreground of the stained glass. The reds, yellows, and greens behind this form a simple geometric pattern. The stained glass is flanked by balconies on either side. The balconies have green bands, geometric grillwork executed in concrete, and smaller stained-glass panels in the same palette of reds, yellow, and greens at the top. The colours of the stained glass, evocative of a rangoli, are vibrant and festive.

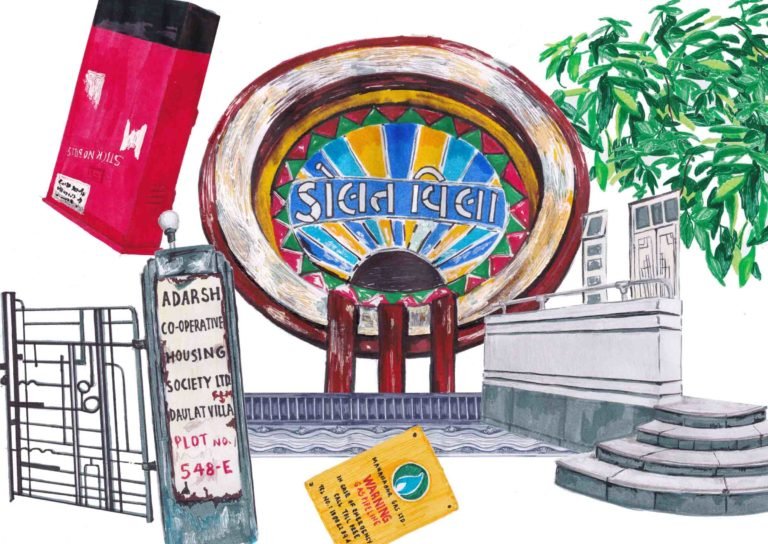

In Daulat Villa (Matunga), another stained-glass, this time uniquely circular, shows the building’s name in Gujarati. Nestled in a ring of red and green zig-zags, the name proudly arcs over a rising sun with blue and yellow rays. The circularity of the stained glass pays homage to porthole windows, while the three red racing bands dropping from it are also Deco. This stained glass is at the centre of the building, couched between two balconies, and above the entrance canopy—it is highly conspicuous. Conspicuous not only because of its placement and that it eclipses many of the building’s other façade adornments, but also because it seems to be signalling that the architects were not afraid of “experiments with Deco.” Their foray into the localising of Deco was by no means furtive. In fact, with the insertion of Gujarati stained glass into the unmistakably Deco porthole window, the integration of elements of Indian culture into Deco seems perfectly complete.

The N M Petit Fasli Agiary, designed by Gregson, Batley & King in 1937-40, at Churchgate is a rare example of a devotional structure executed entirely in Art Deco. Above its towering grey and golden entrance, is golden Gujarati lettering which announces the agiary—“Sheth Nasharvanji Maneckji Petit Fasli Aatashkadah.” The entrance of the Agiary is flanked by two fierce Lamassu figures. Lamassus are protective deities from Assyrian mythology, [11] and are notable fixtures at Zoroastrian fire temples. [12] These hybrid creatures have the head of a human, wings of a bird, and the body of a lion. Here, the ornate wings and flowing beard usually associated with lamassus have been traded in for simple, clean geometric: a classic Deco look. Atop the roof of the fire temple is a small columned tower with a golden, stylised flame that crowns it. The tower is branded with a low-relief of the highest deity of Zoroastrianism—Ahura Mazda.

Outside of variants of the Devanagari script with Hindi and Gujarati lettering, special lettering also extended to Urdu. The façade of Ismail Begmuhammad High School (Mohammed Ali Road), an Urdu medium school, is blanketed in a sunburst and pyramid motif. This repeating low-relief motif, executed in plaster, is part of the tropical imagery repertoire popular in Bombay’s Deco. Under a row of such relief work stands pearly white Urdu lettering that spells the school’s name.

This “Bombay Style” of Art Deco, however, wasn’t isolated to primarily residential buildings, such as the Deco Mahals and Villas—in the late 1930s, a cluster of commercial Art Deco buildings were developed in the Fort area of south Bombay. In an almost prescient Times of India article from 1932, a reporter paraphrases Mr. Batley (of Gregson, Batley & King), who felt optimistic about Bombay “developing an architecture of its own.” [13] The reporter goes further to demarcate Fort, which was “scheduled for rebuilding,” as an optimal location for such “architectural improvement” that could be developed on lines that were “distinctive of Bombay.” [14]

Almost five years later, in 1937, in seeming fulfillment of the article’s prophecy, the New India Assurance building was built. This building was in every sense, a building of “New India.” India’s claim to sovereignty is not only prefaced by the building’s name, but it is also explicitly illustrated by the bas-reliefs on its façade. These bas-reliefs are a signal that Bombay did indeed develop an “architecture of its own.” Sculpted by N.G. Pansare, one of the pillars by the entrance of the building depicts a larger-than-life worker in the foreground with gears and cogs behind him. Above another pillar to the left of the entranceway, is a relief of a woman holding a diya; this imagery may allude to the light of knowledge. Another relief, an ode to the Swadeshi movement and a return to native roots, shows a woman with the charkha (spinning wheel).

This idea of Swadeshi self-sufficiency would have held currency with Dorabji Tata, who was motivated to found New India Assurance as a “powerful national company” [15] so as to challenge the “few foreign insurers who monopolised” the field. In fact, the writer of the Times of India article from 1932 goes as far as to advocate for an architectural “awakening, a realisation of what can be done in some sort of swadeshi style.” Although the writer may have spoken a little cursorily, without compete appreciation of what the Swadeshi movement meant to India’s independence, his words had real bearing with respect to not only the New India Assurance building and the company’s origins, but also to the start of a lot of other insurance companies that eventually established Art Deco office buildings in Fort.

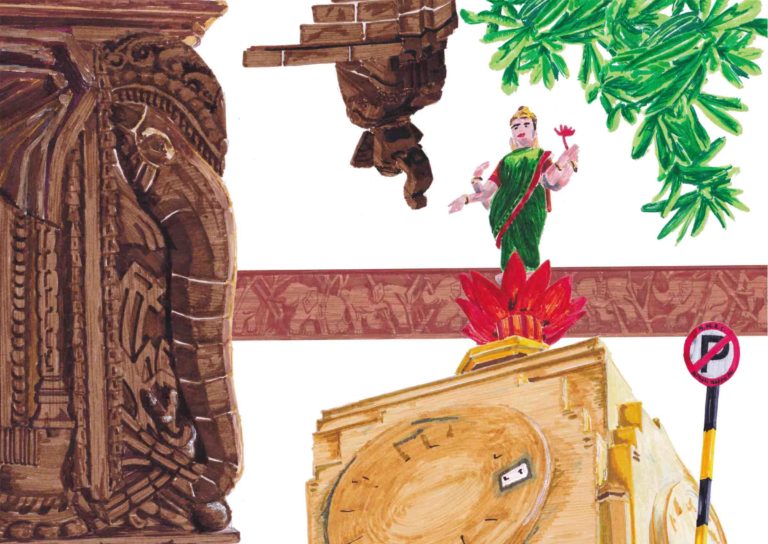

One such example is the Lakshmi Insurance Building designed by Master, Sathe & Bhuta and opened in 1938. The Lakshmi Insurance Company was founded by Lala Lajpatrai, Pandit Motilal Nehru, and Pandit Shantaram and the building was inaugurated by Subash Chandra Bose — all of whom were national leaders devoted to the independence struggle and prominent in the Swadeshi movement. [16] Courtesy of sculptor Ramachandra Pandurang Kamat, the building is crowned by an 18- foot bronze statue of the goddess Lakshmi which proudly stands atop what was once a clocktower; hence the building draws from Hindu mythology as Lakshmi, goddess of wealth and fortune, aptly fits the brand of an insurance company. Other elements of Lakshmi’s iconography, such as the lotus and her mount, the elephant, are also recurring motifs on the building’s façade. For instance, a set of intricate yet monumental red sandstone bas-relief sculptures of elephants flank the interior entrance of the building. A set of smaller twin elephants make an appearance as stand-alone sculptures on the roof of the building, and a red bas-relief frieze of even smaller elephants curls around the façade of the building.

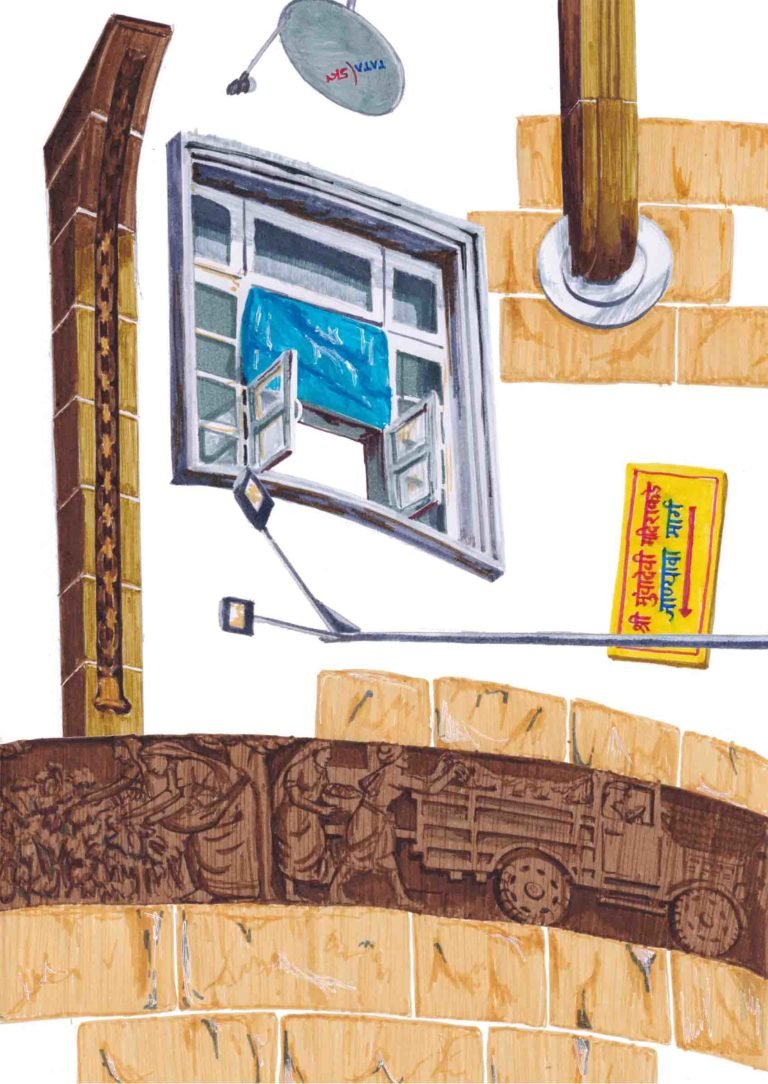

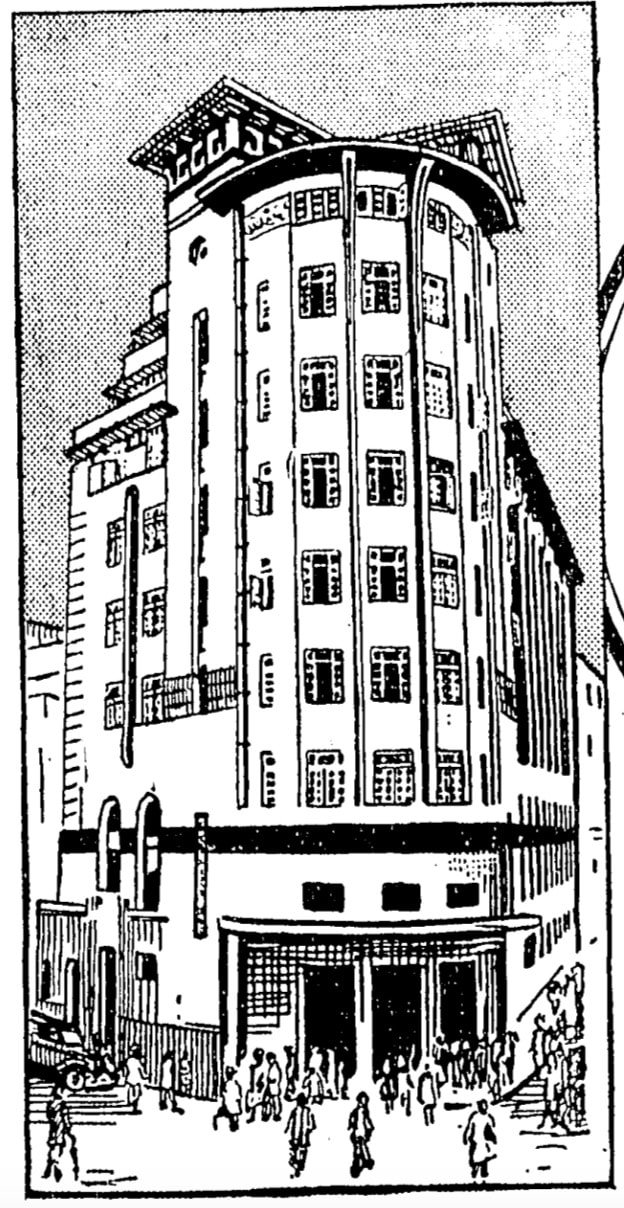

Another commercial “Bombay Style” Art Deco building also built in 1938 with a winding bas-relief frieze is the Cotton Exchange Building in Kalbadevi. Unlike the Lakshmi Insurance Building which relied heavily on spiritual imagery to bolster its aesthetic cohesiveness, the Cotton Exchange Building, similar to the New India Assurance building, draws inspiration from Indian agriculture and cottage industries. The building, designed by Sykes, Patker & Divecha, was declared “Bombay’s first ‘skyscraper.’” [17] Presently a jewelry market, as the name suggests, the Cotton Exchange Building, was formerly a hub for cotton trade. The cottony origins of the building remain chronicled in the bas-relief that wraps around the façade of the building. It not only outlines the journey of cotton, from fields to trade, but also grounds this commercial building in India’s ubiquitous agrarian and rural life.

The original structure of the Cotton Exchange Building comprises of a rounded corner at the intersection of two streets. All throughout this rounded corner runs the bas-relief about Indian agriculture and cotton. At this corner is the main, canopied entrance above which rise two towers on either side. Leading up to the towers are vertical columns with the relief of a bell carved into them.

The fact that—akin to the New India Assurance and Lakshmi Insurance buildings—the form of the Cotton Exchange Building too was governed by Deco, yet accentuated by Indian flourishes was not lost on the people of 1938 Bombay. In a comprehensive Times of India “supplement” that covered the opening of the building on August 31st, 1938, the writer is clever to observe that the building is in “modern style,” that is in Deco, while it simultaneously and “appropriately [strikes] an Indian note.” [18] The writer further details how the “curved section of frontage,” the “twin towers at the top,” the “upright mullions, windows and other features” lend further “emphasis to the extra height” and help “mark the vertical treatment” of the building. The writer essentially describes “streamlining” long before the term was popularly used in the parlance of Deco talk. Much like New India Assurance, Lakshmi Insurance, and a number of other insurance companies housed in Fort, the Cotton Exchange was also established with nationalistic aspirations towards independence. The Cotton Exchange was consecrated with a havan (votive ritual) performed by Vallabhai Patel, future Deputy Prime Minister of independent India, who hoisted the Congress flag over the building, declaring the “freedom to trade.” [19]

Soon it becomes apparent that this unique “Bombay Style” of Deco owes much to Bombay’s many residents and their communities that settled and flourished in the city. For instance Mohammed Ali Road had been identified as the “Muslim quarters of the town,” since 1877 and was infamous, even then, for its “narrow cross streets” which were “crowded with traffic as to be almost impassible.” [20] Between 1905 and 1930 there was a concerted effort to open up these decongested areas. As a result, by 1935, new buildings and plots were created and were constructed in the Art Deco style. This “transformed the avenue” and brought a “sense of order” to the area. [21] And apart from bringing a sense of order, it also brought a host of buildings—ranging from Akbar Chambers to Mohammedi House—that were a somewhat unified reflection of the community that inhabited them. Similarly, Deco suburban housing colonies developed in the 1930s with their gujarati lettering and traditionally Hindu organisation of house spaces or buildings organised around an Agiary, were evocative of gujarati and Parsi communities respectively. Early Marwari merchants from Rajasthan, prolific in the trade of opium and cotton, “settled around the Kalbadevi area” by the eighteenth century. [22] The roots they laid down were sustained and in 1938, the Cotton Exchange Building opened its doors. Bombay, long known as a maritime hub for trade and considered the business capital of the city, was also a centre for revolutionary and self-deterministic dialogue during the freedom struggle, as is evidenced by the conglomerate of Deco buildings in Fort. Bombay Deco has become symbolic of a wonderful syncretism, yet this syncretism is symptomatic of the varied people—from merchants, thinkers, and religious communities—that called Bombay home.

Tarini N Gandhi for Art Deco Mumbai

Tarini is currently in her third-year studying Studio Art at Pomona College, California. She is passionate about design, illustrating her friends, tinkering with the risograph machine, Postcolonial Literature, and stories that have traditionally been cast to the sidelines. Despite blistering paint, corroding grills, and cracked tiles, she still finds much of Bombay’s architecture perfectly charming, and wants to learn more about it.

Renderings showcased in this article are available as “Bombay Deco”, a set of 8 illustrated postcards, at Art Deco Mumbai’s online store.