A cinematic ode to Bombay’s Deco of the 30s-40s.

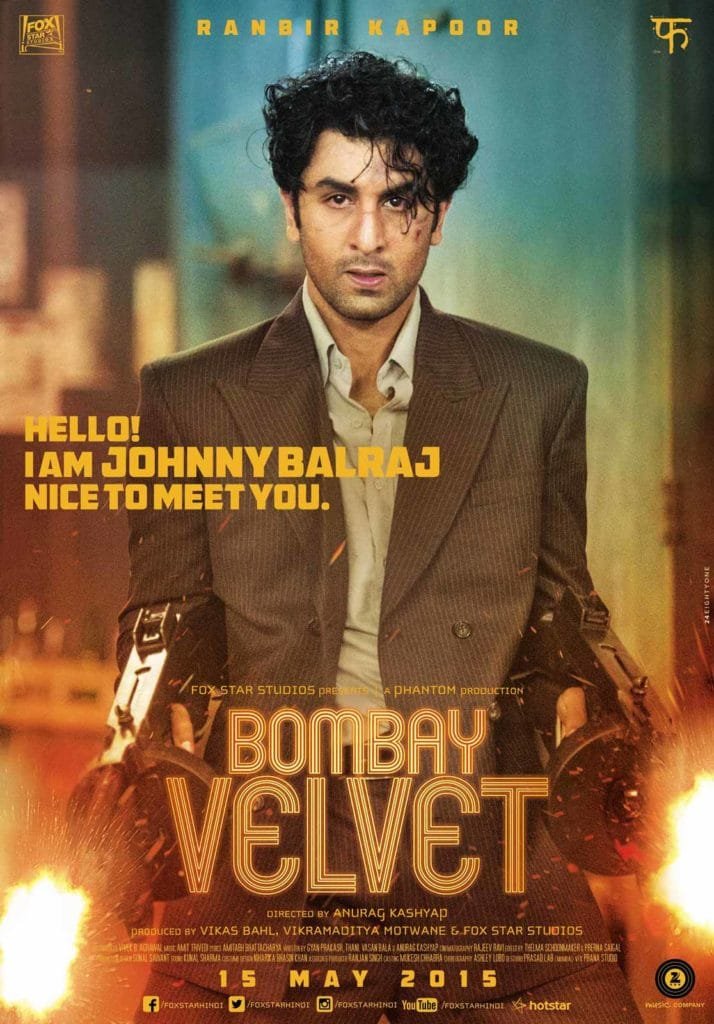

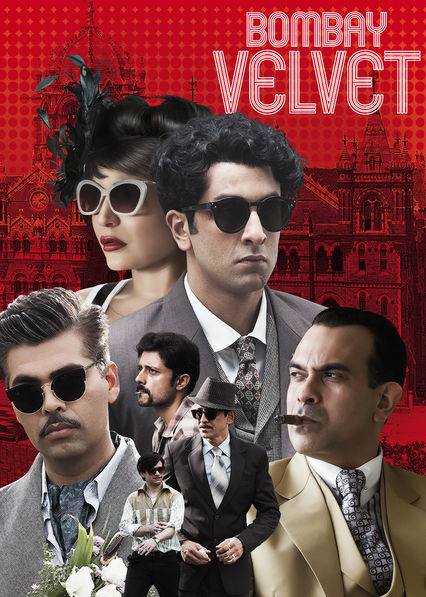

‘He used to be a big shot’, laments Priscilla Lane, cradling a dead James Cagney as the curtain comes down on the ‘Roaring Twenties’ to a full house cinema palace, in the film Bombay Velvet. The American blockbuster is playing 8480 miles away from the country of its making, in Bombay. An enraptured Johnny Balraj (Ranbir Kapoor) mouths those very words from the film, in a borrowed accent, his fingers curled into a mock gun. But the import of what he repeats is apt, if not immediate in the Bombay of the late 50s. From a protagonist who, like Cagney in the Roaring Twenties dreams of making it big in the city, to the city itself flirting with new ideas of modernism, Bombay Velvet’s world is one coloured by aspirations.

In what is perhaps one of the most fleeting initiations into Bombay’s history– Kaizad Khambata (Karan Johar) nonchalantly tells Johnny, ‘Seven islands, beech me pani, pani ko bhar diya, one city-Bombay’. Bombay was this and much more at the beginning of the twentieth century. While the sea separating the seven islands from each other had already been filled in the preceding centuries, new land was fervently being reclaimed from it, with the Backbay Reclamation Scheme nearing fruition in the 1930s. In conversation with us, Director Anurag Kashyap explains how he started writing Bombay Velvet to document the ambitious, corrupt and glamourous side associated with the creation of Nariman Point. The story was originally meant to be one of four-part storytelling projects through which he aspired to visually document spaces of Bombay. Simultaneously written, these four projects had already been fleshed out and clues of the upcoming stories had been incorporated into the story of Bombay Velvet through songs, and side plots.

Twentieth century modernism, powered by Western industrial capitalism was relentlessly ambitious. Machines had opened up a new realm of human imagination and possibilities. Surmounting the limitations of space and time, communication and transport had speeded up the potential of intellectual and cultural exchanges. Bombay, the second city of the British empire and an integral node connecting global trading networks, was at the vanguard of internalising the ethos of this new modernism. This is reflected in a most vocal assertion by Lord Brabourne, the Governor of Bombay Presidency who pinned the city as ‘the most industrialised in the subcontinent with an enviable standard of living and education.’ Consumerism, a necessary corollary to the capitalist way of life, was deftly claiming its share of people’s disposable incomes, at the heart of which Bombay found itself. Between the 1930s and 50s, this ‘optimism of a new era’ also spilled over to the public culture in Bombay, sprouting new cinema palaces, jazz bars, clubs and Art Deco wonders. This promise of Bombay is lyrically surmised in the following line from a song in the film, ‘Jaata kaha hai deewane, sab kuch yaha hai sanam.’ [‘Where do you go Oh beloved!, when all is here (in Bombay).]’

Cinema can be both a visual raconteur and testifier of times past; period films all the more so. Bombay Velvet was envisioned as an ode to the city of Bombay of the 40s 50s and 60s. Having incubated for nearly seven years as a script in the making, it took up to a year to build the sets in Sri Lanka and a year each for shooting and post production. As director Anurag Kashyap succinctly puts it, “It is the story of the city and when you make a film like that, you have to create a city without there being any.”

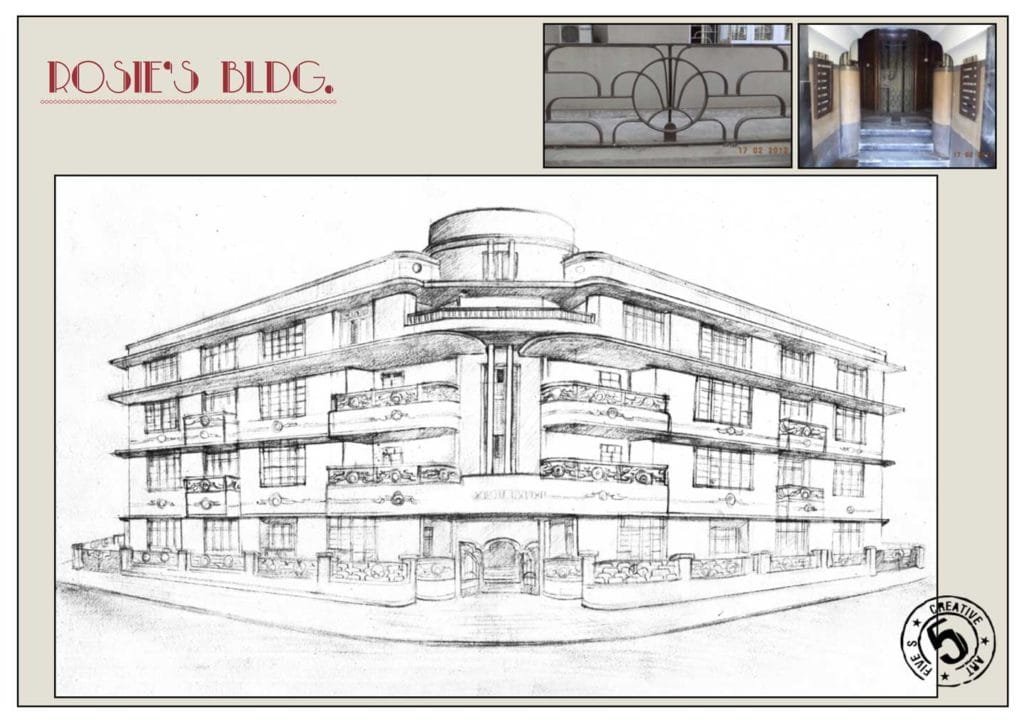

But creating a city from scratch that would mirror its historical self was no mean feat. Sonal Sawant, Production Designer of Bombay Velvet enumerates why it was inevitable that an entire set be erected in Sri Lanka. According to her, the crew had tried shooting at several locations in Mumbai, Gujarat, Hyderabad and Kolkata. But in order to shoot one scene, they ended up visiting several locations, which ultimately was not viable. It was next to impossible to shoot at historic locations in Mumbai amidst screeching traffic and security concerns. Not to mention the foliage and skylines that had considerably altered since the 60s. The last straw was comparative costs.

In Sri Lanka, the Government was willing to subsidise costs in return for technical expertise from Bollywood that would help incubate its own fledgling film industry. And so the call was made. At Tissamaharama, the crew had to level out 9 acres of wasteland to build the city, and Sonal proudly affirms that everything from plumbing works to electric lighting to water supply functioned as it would in a living city. Sonal’s keen eye for detail left no stone unturned and Anurag’s epithet for her as a ‘perfectionist to a fault’ seems only justified. As Ranbir Kapoor fittingly remarks, “The scale of Bombay Velvet is the believability of Bombay in the 1950s. If we are able to achieve that then we have been able to achieve the scale of the film.”

The believability of Bombay in the 1950s is an important catch. Very few cities in the subcontinent could claim to rival the dynamism unfolding in Bombay at the time. An inexorable factor that ushered in this ‘new modernism’ in the city was the Art Deco style, one that Bombay Velvet capitalizes on, in almost every frame. Art Deco, although expressed most enthusiastically in the realm of architecture was not limited to or singularly defined by it. As Gyan Prakash notes in his book ‘Mumbai Fables’, which incidentally, Bombay Velvet also draws upon, Art Deco was synonymous with a new fashionable lifestyle that proudly declared ‘the future is here.’

From handpicked Deco jewels like Dhanraj Mahal and Rajjab Mahal that make an appearance in Bombay Velvet, distinctive Deco features can be seen across the spectrum on furniture, costumes and even jewellery.

Art Deco not only embodied but also mobilized the aspirations of Bombay post-Independence. Between the austerity and self-abnegation of Gandhi versus the state centered socialism of Nehru, Bombay had chosen a radical alternative. While Art Deco was too foreign to be acceptable by many nationalists, for many industrialists and architects in Bombay who were the chief proprietors of the style, Art Deco was a reflection of Bombay’s internationalism; that of a global port city.

Gone were the days of joint families living together in stately bungalows with a retinue of servants. The Backbay Reclamation Scheme, having opened up virgin plots of land, new apartment blocks conducive to nuclear families and championing an independent lifestyle peppered the promenade of Marine Drive and Oval. Invariably designed in the Art Deco style, these were, as an Indian Civil Service officer at the time put it, ‘a modernistic block of flats shaped like biscuit tins.’ These new apartment flats, unlike any before them, also sported avant garde innovations such as air conditioners and refrigerators.

Its allure was not limited to the elites alone, for its cost effectiveness and suitability to mass production, allowed many newly mobile middle classes to experiment with the style in the suburbs of Matunga, Dadar etc. In a conversation with colonial Bombay cinema expert Prof. Debashree Mukherjee of Columbia University, she pointed out how Art Deco’s promise was the same as the promise of the ‘Urbs Prima in Indis’- glamour, modernity and cosmopolitanism.

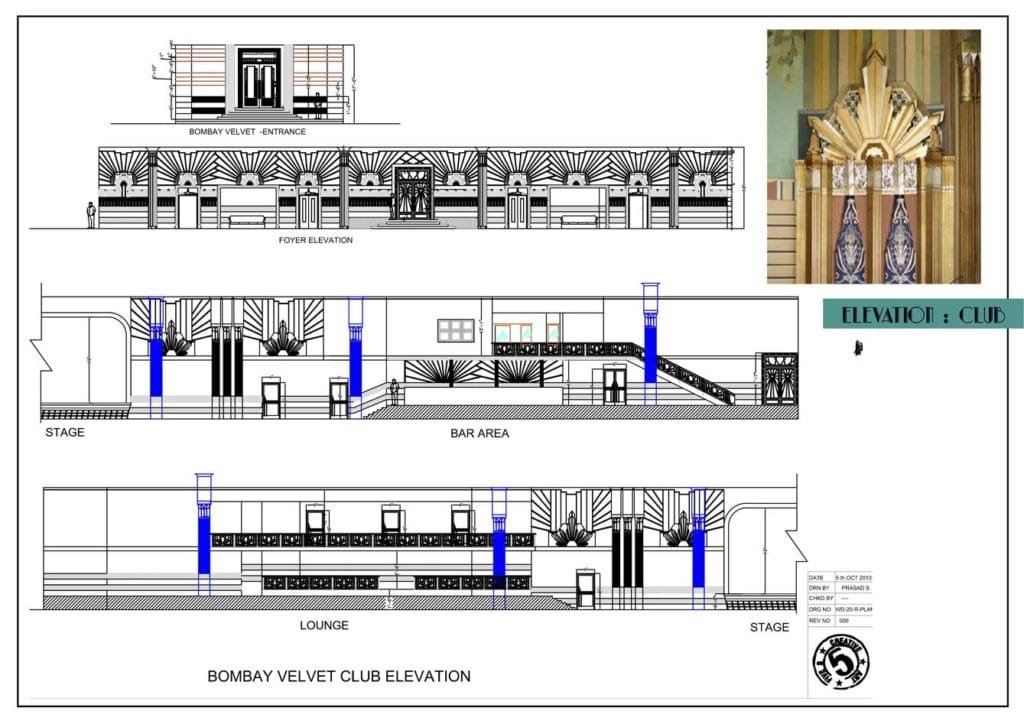

It was but inevitable that Art Deco would be the dominant medium of expression to convey the periodization of Bombay in Bombay Velvet. From the gorgeously conceptualized Bombay Velvet Club to the Deco apartments many of the film’s characters live in, even minute details such as stair railing designs and music boards have been curated in Deco. Speaking of the research that went into producing these designs Sonal Sawant remarks at the innumerable walks she and her crew took around Marine Drive and other Deco neighbourhoods. “Our crew was not equipped to grant us access into these buildings but we still persisted with the residents to at least let us into the lobby to look at some of the beautiful terrazzo floorings,” she says. According to Sonal, films like Bombay Velvet are an exception rather than the rule, allowing up to 6 months for research alone, to recce the city and cull information, something that very few films prioritise.

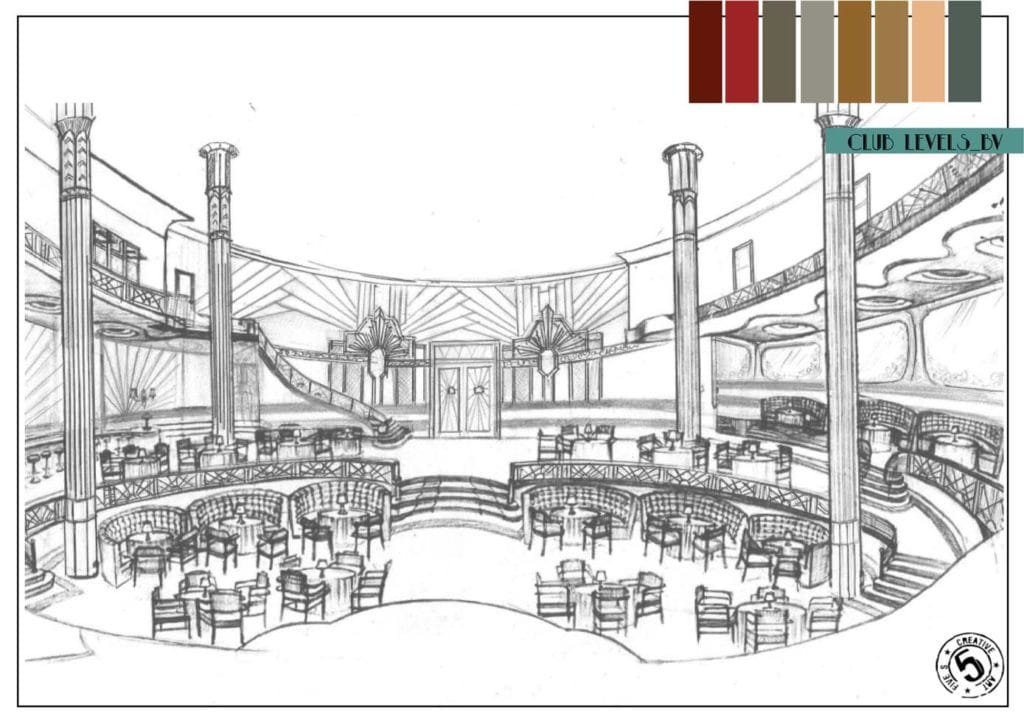

Any conversation on Bombay Velvet and Art Deco is superfluous without mention of the Bombay Velvet Club, an extravagant Deco inspired club that protagonist Johnny Balraj runs in the film. Deco’s use here is not only indicative of the aesthetic articulation of the interiors that scream glamour and flamboyance, but is also a comment on the aspirations of Johnny, his need to be associated with spaces that allude to wealth. Used metaphorically, Deco ratifies that very aspiration.

The Deco club was Johnny’s gateway to be the ‘big shot’ he had always imagined himself to be. For Sonal who envisioned and designed the Club, it had to be distinct from every other character and space the film captured. “I needed it to be dramatic in a way that every time you look at it, it pops out and makes you go ‘Woah!’” she says. The inspiration for the design of the Club is owed to the Fox Club in New Orleans and the Design Team’s mood board for the club was a collage of the interiors, ambience and aesthetics of clubs from across the globe.

Anyone familiar with popular landmarks in Bombay will know at first glance that the exterior facade of the Bombay Velvet Club resembles two iconic theatres in the city- the Regal and Metro cinemas. And that is no coincidence. Dhara Jain, Researcher and Assistant Production Designer of Bombay Velvet explains that the club was designed to resemble a theatre since it was run by Johnny who was besotted by the foreign films he saw in the theatres of the time. Films were partners in the modernising project as they depended on the technology of the camera and Bombay pioneered the film industry in the subcontinent. Actors, musicians, script writers and others trickled into the city they knew had a penchant for their art.

The modern picture palaces that came up in the 1930s, Regal being the first of them, revolutionized the public culture of Bombay. An evening spent at Regal was no less than one at a theatre in New York. With its neon coloured façade, bold orange and green interiors, centralized air conditioning and an underground parking garage, Regal and its other Art Deco compatriots stood at the confluence of the East with the West. They fostered within their walls global cultural imports like Hollywood films, cabarets, ice skating rings, wine and dine restaurants, bars and the like. While all of them still retained some form of class based social segregation, they were, as one Times of India article announced in 1938, ‘A Cinema for all Bombay.’ These theatres were one of the first public spaces that marked an overwhelming presence of women and also encouraged mixing of the sexes. It was acceptable for young men in Bombay at the time to ask women for a drink or a dance at these theatres.

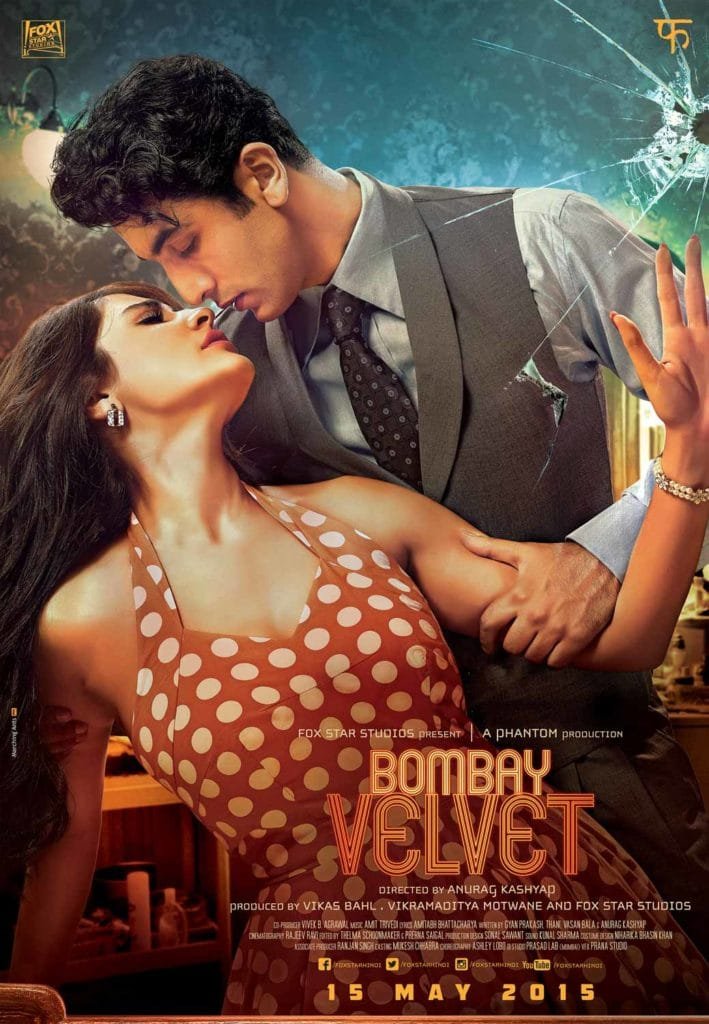

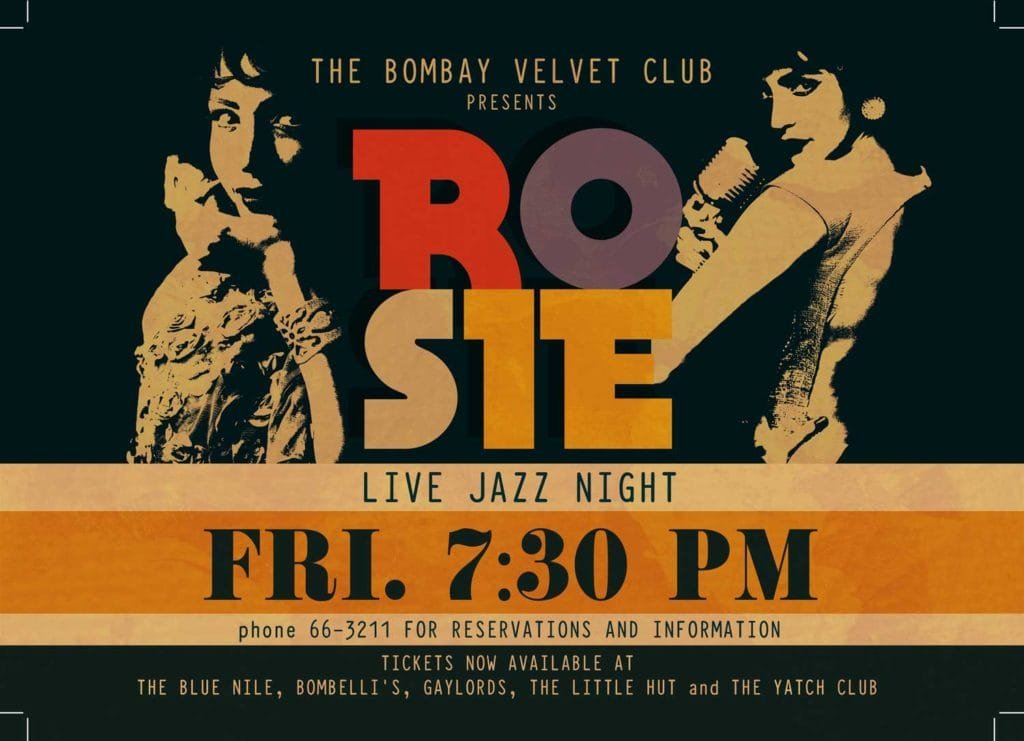

Like Art Deco, Jazz symbolised a radical break from classical styles, in this case music, and Bombay Velvet’s soundtrack features some of the best swing jazz beats from the 50s by Amit Trivedi. Director Anurag Kashyap went to Prague to record all the songs for the film and even got musicians from there to play instruments in the film. Jazz was zealously lapped up in Bombay in the 50s and 60s and black American Jazz singers like Leon Abbey and Goan Jazz bands such as Chic Chocolate were overnight hits in the city. As Bombay became the movie capital of India, jazz tunes were inflected with native tunes to produce some scintillating scores such as ‘Mera naam Chin Chin Chu’ and ‘Babuji Dheere Chalna.’ Incidentally, the inspiration for Anushka’s character Rosie is a legendary Goan Jazz singer Lorna Cordeiro who used to perform at the Jazz clubs in Bombay. She lives in Goa to this day and still sings. Rosie’s rise to fame in the film is facilitated by Jazz, elevating her to instant stardom, at the same time evocative of female lead singers holding their own in Bombay.

Bombay Velvet’s sweep encases not just the glamorous city and its elite but also its proletariat and poor. In fact, Johnny straddles both worlds as he tries to cross over from the latter to the former. By juxtaposing the mill lands, fight clubs, and red light zones such as Falkland Road alongside the modern plush cityscape, the film reflects several diametrically opposed ways of life co-existing within a shared space. While the contrast between the ‘destitute’ city and the city of ‘high rises’ is an often exploited trope in Bollywood cinema, Dr. Ranjani Mazumdar explains in her book ‘Bombay Cinema’, that with the coming of corporate film making brands such as Yash Raj Films, the outdoor experiences of a city are more often than not left unexposed. According to her, the ‘panoramic interior’ has substituted the chawls, trains and crowds, which despite being central to any narrative on the city are increasingly marginalized. Bombay Velvet is a remarkable exception in that regard since the entire city was built and shot outdoors and features the glamorous city alongside the gritty city.

In one of the scenes from the film when Rosie implores Johnny to leave the city, he retorts by reminding her that what lies outside Bombay is India, and India is where poverty is. The film banks on this familiar notion of a ‘better life’ waiting in the wings in ‘the city of dreams’ where an underdog pushes his luck amidst a barrage of corruption, crime syndicates, tabloid wars, unionism and capitalist usurpations. It is also a singeing reminder of a city raised on the blood and sweat of millions. But what uniquely distinguishes Bombay Velvet however, is its treatment of the period, harking back to nostalgia without any hint of lament. For those who love Bombay and have only read about or seen glimpses of the city’s past, the film has a refreshing take on the city’s landscape, replete with trams and retro advertisements, fashion and lifestyle choices of the time, and the spectacular promenade of Marine Drive without any of today’s high rises in the backdrop. It is an ode to the Art Deco style that flourished in Bombay from early 30s-50s, and a visual treat for all Art Deco buffs. Bombay Velvet is, as Anurag Kashyap always intended it to be, the ‘Definitive Bombay Noir.’

Meera Panicker and Atul Kumar for Art Deco Mumbai

Meera believes the past empowers the present and is enthusiastic about democratising history and making it more accessible. Her research interests include exploring Mumbai’s rich cosmopolitan, architectural and cultural heritage. She is a History graduate from St. Xaviers College, Mumbai and a 2017 awardee of the Erasmus Mundus scholarship at SOAS University, London. She is presently pursuing her master’s in mediaeval history at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.

Atul is Trustee, Art Deco Mumbai Trust

(Read about Sonal Sawant and Dhara Jain, whose vision and research built the Deco city out of thin air in Picture Abhi Baaki Hai)

Click here to view “Liberty Cinema: The Showplace of the Nation”, a short film by Art Deco Mumbai Trust.