If New York was the original Hollywood on the Hudson, Bombay (now called Mumbai) has been and still is Bollywood, the capital of Indian cinema. While Hollywood produces some 600 films each year, India creates over 1,100 not only in Mumbai but also Calcutta, Chennai (formerly Madras), and Hyderabad. (Mehta, 2005, 57) The audience numbers 3.6 billion (a billion more than Hollywood’s), and Indian films are wildly popular in China, Africa, Russia, Southeast Asia, Middle East, Latin America, and South Asian diasporic communities too. Every day 14 million Indians watch a film in one of 13,000 cinemas. (Mehta, 2004, 349) Cinemas hire security guards to maintain order in the fierce competition for seats.

Lasting three hours or more, films screen in tents, theatres, storefronts, multiplexes, and the open air. Stores and street hawkers sell legal and illegal videos and DVD’s for home consumption. Mumbai is the home to Filmi City, a five hundred-acre complex in the northern suburbs with sound stages for song and dance extravaganzas (at least two to three such numbers are required in each film) as well as back lots filled with mansions, villages, schoolhouses, and police stations. (Mehta, 58) While the Hollywood juggernaut has crushed other national cinemas, it accounts for barely five percent of the Indian market. (Mehta, 349)

The media avidly track the lives, loves, tragedies, triumphs, and careers of Bollywood megastars like Shah Rukh Khan and Aishwarya Rai. Papering the walls of shops, stalls, and even homes, their images form the textures of everyday life as well as a pantheon of saints, gods, and goddesses. Shop owners and street hawkers sell likenesses of Khan, Rai, other Bollywood deities along with Vishnu, Parvati, Jesus Christ, and Mother Teresa to their devotees. Street and studio photographers collage or photoshop images where customers appear as protagonists in their own films or socialize with favourite stars. (Torgovnik, 2003, 74-76 and Pinney, 1997, 210-213)

Although associated with divine and everyday realms, Indian films often become embroiled in contemporary social and political issues. Theatres showing films deemed objectionable to traditional values are targets of vandalism and violence. Students associated with Shiv Sena, a Hindu fundamentalist party, smashed the windows and burned effigies in front of the Mumbai theatre screening Girlfriends, a film about lesbianism, in 2004. (BBC News website). In 2006 Bollywood films became tools of diplomacy. Banned in Pakistan since 1965, they have circulated there only through pirated copies. But President Pervez Musharraf gave special dispensation for public screenings of the recently released Taj Mahal and The Great Mughal (a 1946 film often called India’s Gone with the Wind) in Lahore. Celebrating Islamic empires of the past, both films were deemed safe and respectful choices. Fardeen Khan, Indian star of Taj Mahal and a Muslim like several Bollywood idols, said at the Lahore premiere: “I think cricket and films are two aspects that have kept the two countries together.” (Masood, 2006, A4)

Since films were first exhibited and then created in India, they have raised questions about tradition and modernity; local and global; colonial and national; and every day and otherworldly. In this paper, I explore how the Regal, Metro, Eros, and Liberty theatres, all picture palaces from the thirties and forties, and the films they screened became and are still imbricated in these same issues. While popular and scholarly literature on Indian cinema has proliferated, there is comparatively little interest in the buildings where the films were exhibited. And today many of these pictures palaces are being demolished or converted into multiplexes.

Located in the Fort area (stronghold of the British Raj), these buildings inscribed new urban forms associated with modernity and technology on the city. They were and are still landmarks as well as points of reference, formally and informally mapping Bombay. Addresses on business cards, tourist guides, and advertisements reference the cinemas, and nearby shops, offices, and restaurants appropriate their names.

Their architects, the first generation of Indian architects educated and trained in western professional models, chose to work in a supple design language, Art Deco. It could express urbanity, progress, and sophistication as well as traditional materials, handicrafts, and iconography. Called moderne or modernistic during the period, this work was known as Art Deco beginning in the sixties, a reference to the 1925 international decorative arts exposition held in Paris where it was featured. (Hillier, 1968, 11-13)

Yet Art Deco, the term used here, was derided then and now for being insufficiently modern, that is, deficient in artistic, structural, and theoretical rigor. Appalled by the chaos of “stainless steel gargoyles of the Chrysler Building to the fantastic mooring atop the Empire State,” Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, looked for salvation in the International Style. (Barr, 1932, 12-13). These buildings were about commerce and fashion, not architecture; they were flashy; mindless, and Barr hoped, soon to pass. The precious materials and extravagant ornament of Art Deco skyscrapers from the twenties like the Chrysler Building were a hand-crafted, not an industrial age, modernism. Even the simpler streamlined Art Deco from the thirties and forties, inspired by aerodynamic forms of airplanes, automobiles, and ocean liners, was criticized for mixing ornament, polychromy, and theatricality with modern materials, abstraction, and building typologies.

Critic Paul Goldberger described the streamlined buildings of Miami Beach as an architectural mongrel: “one part International Style puritanism and one part Art Deco indulgence.” (Goldberger, 2000, 7)

The uneasiness with Art Deco is reminiscent of western reactions to Indian cinema. Bollywood’s hybridity, which melds fantasy and reality, epic and melodrama, action and musical in a single film, is too simple, melodramatic, and irrational for most western critics and audiences. (Mehta, 2005, 57-58)

This distaste for Art Deco also echoes the reaction of historian Banister Fletcher when he confronted “those other styles,” that is, Indian, Chinese, Japanese, Central American, and Saracenic architecture. Fletcher wrote one of the first global surveys when he published A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method in 1896. While western architecture was “allied and progressive,” Fletcher described as eastern works as “non- historical styles . . . detached from western art and exercis[ing] little direct influence on it.” His “Tree of Architecture” succinctly illustrated his thesis with a main trunk growing from Greek, Roman, and Romanesque into American work and then isolated branches for Indian, Mexican, Chinese, and Japanese buildings. “The non-historical styles,” Fletcher elaborated, can scarcely be as interesting from an architect’s point of view as those of Europe, which have progressed by the successive solution of constructive problems, resolutely met and overcome.” Whereas with the “non-historical styles” he continued, “the decorative seems generally to have outweighed all other considerations.” (Fletcher 1924 ed., 784 and 789) While western architecture was implicitly masculine (resolute, 3 rational, and progressive), eastern architecture seemed stereotypically feminine (irrational, superficial, and ornamental). Surely Fletcher would have felt Art Deco, a “girlie” modernism in contrast to the rigorous and logical International Style, was appropriate for India. It was the other modernism for the other.

Film in India, like Art Deco buildings, was a hybrid. It blurred, we shall see, the lines between modern and traditional; real and fantastic; village and metropolis; and colonialism and nationalism. Only seven months after the Lumière Brothers introduced moving pictures to the West in 1896, their operators exhibited a program of actualitiés (scenes of modern life like steam locomotives lasting less than a minute) to Bombay audiences. The first screening took place in Watson’s Hotel, a prefabricated cast-iron building in the Fort area. (Dwivedi and Mehrotra, 1999, 96) Appropriately, the modern medium of film made its debut in a metal, prefabricated structure.

Yet Europeans never really created a film industry in India. But Indian directors like D. G. Phalke (considered the father of Indian cinema) did, screening their first features as early as 1912/1913. Based on the ancient epics of Ram and Krishna and known as devotionals, these films featured plots and characters familiar from literature and folk performances. While Phalke’s works had their premieres in Bombay theatres, they were also presented out-of-doors near the shrines and temples of the very gods and goddesses featured in the films. Eschewing advertisements in the English language press, Phalke made his films for an Indian audience. (Bjerregaard, 2003, 202-204) A scholar and photographer with a passion for acting and magic, he created an Indian national cinema from modern technologies and traditional culture. And eventually Art Deco picture palaces like the Liberty bridged the divide between Watson’s Hotel where an elite watched the Lumière Brothers’ scenes of modern life and the open-air “theatres” where villagers saw Phalke’s devotionals.

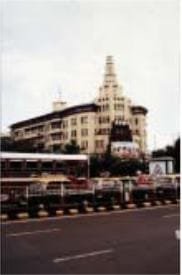

Starved for space in Bombay (a city formed from seven islands), land was reclaimed in the Back-Bay area by the thirties. And Art Deco created a unified urban texture for Back Bay hotels, stores, cinemas, and apartments. It was an architecture set apart from the bungalows set in compounds built by the English. (Jaffer, 2003, 384) Some of the architects and engineers were foreigners like Charles Stevens who designed the Regal in 1933, the first theatre built exclusively for cinema. Stevens represented the Raj; his father was Frederick William Stevens who designed Victoria Terminus, Bombay’s High Victorian Gothic railroad station, between 1878 and 1888. (Dwivedi and Mehrotra, 10-11 and 56) The Metro picture palace was another kind of imperialism, Hollywood’s cultural invasion. Its very name indicated the theatre screened films produced by Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer Studios. Designed by acclaimed theatre architect Thomas W. Lamb (who entrusted the work to Bombay architect D. W. Ditchburn), the Metro was a multipurpose building, developed to extract maximum revenues from its valuable site. The Metro and other Bombay picture palaces included bars, offices, ballrooms, restaurants, underground garages, penthouse apartments, and even an ice skating rink. They were also the first air-conditioned buildings in this hot and humid city. (Ibid., 108). The architect of the Eros Cinema, however, was Sohrabji Bhedwar. Completed in 1938, the Eros occupies a prominent space, across from Churchgate Station, a major transportation center (Fig 1). Across from the Oval Maidan (a large open space in Bombay appropriated for cricket pitches but also political demonstrations), it also anchors a row of Art Deco buildings confronting the High Victorian Gothic institutions of the Raj (the High Court, University Library Tower, and Secretariat) on the other side of the green. A tower with v-shaped wings splayed behind it, the Eros was an architectural challenge, influenced by Art Deco setback skyscrapers but also imperial Mughal and Hindu religious architectures.

Bhedwar faced his building with red sandstone from Agra (used for the Red Fort there). He painted other details and moldings in a similar hue against the creamy yellow walls and tower. Projecting cornices on the wings were modelled after traditional dripstones, chajjas, from both Hindu and Mughal buildings. Although no longer extant, the interior decoration combined reliefs and murals of movie-making with tropical landscapes, the Taj Mahal, and Hindu temples. Bhedwar, like the filmmaker Phalke, felt comfortable with traditional forms and iconography and modern technology. The phallic tower crowning the complex recalls a Shiv linga as well as New York skyscrapers (Mumbai, like Manhattan, has always been the financial capital of India) from the twenties and thirties.

Its very name, Eros, surely made prudish colonizers like those E. M. Forster skewered in A Passage to India (1924) squirm. In its siting, architecture, and Indian films it screened, Bedhwar’s Eros challenged British and western monopolies on defining India’s past, present, and future. It was, what Jyoti Hosagrahar (2006), has termed an indigenous modernity, a negotiation between tradition and the modern through urbanism and architecture. But this cinema was also an architectural provocation at the time of the Indian struggle for independence. Indian cinema and its Indo-Deco pictures palaces were also about Mohandas Gandhi’s swadeshi campaign (self-sufficiency, which meant boycotting British and foreign products and reviving traditional handicrafts like khadi, homespun cloth.) They were another path to swaraj (self-rule) and future achievements.

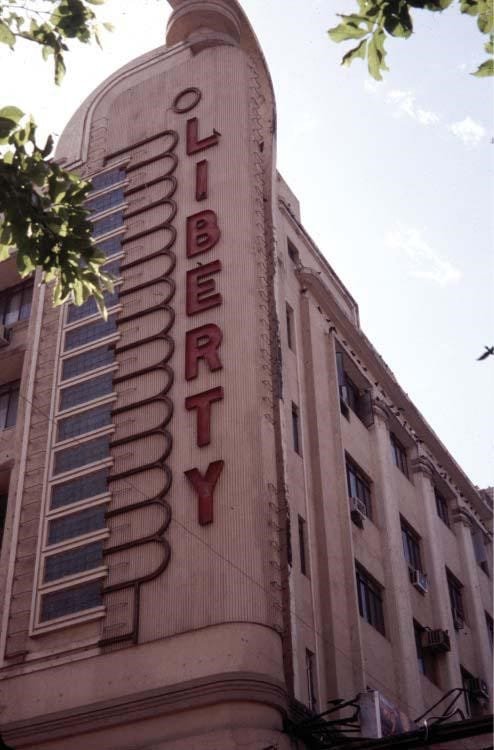

The Liberty Theatre was another provocative name for an Indian picture palace. And it was expressly for the screening of Hindi films for an Indian audience. Begun in the very year of Indian independence, the Liberty opened to the public in 1950. A souvenir booklet (Fig 2) commemorating the theatre’s completion explicitly dedicated the building and films it screened to the new nation-state:

A major milestone is passed in the history of showmanship in India. It [the Liberty Theatre] marks the beginning of the showman’s consciousness of his product. It is a statement to the Indian people that no theatre can be too good for them or for Indian pictures. To the Indian picture-goer who complained that the finest facilities were being used to show foreign products, the Liberty comes as the promise of a brighter future

. . . in the shape of an ultra-modern, air-conditioned luxury cinema dedicated to showing the best of Indian films. (1950, n. page.)

Ironically, the original architect was M. A. Riddley Abbott, but he perished in a plane crash, a suitably modern demise. And W. M. Namjoshi, who apparently had no former training, took over the project, designing the exterior and interiors. Little is known about Namjoshi (like Bedhwar and Abbott a subject in need of future research), but he worked as a factory foreman and draftsman before establishing a successful furniture and interior design practice. Namjoshi designed about thirty cinemas in India. ( Vinnels and Skelly, 2002, 107-110) The Liberty too was an indigenous modernism, honouring Indian traditions but also projecting into Jawaharlal Nehru’s modern future. As proudly noted in the souvenir booklet, it utilized teak, cedar, marble, stucco, and etched glass from both India and the world. Technologies like a Bauer sound system from Germany and Carrier air conditioning unit (still functioning today) from the United States were also used. Local, regional, and international craftsmen, manufacturers, and suppliers who contributed to the Liberty’s design and construction were all listed in the commemorative publication. 2

Its architecture features a prominent streamlined tower (with the theatre name inscribed in neon lighting) at one end, recalling the shikharas crowning Hindu temples.

Built-in seating at the main entrance is not only a modern amenity but also recalls the benches incorporated into traditional Tamil Nadu house fronts, creating what is known as a “talking street” for neighbours ensconced in these outdoor living rooms.

The Liberty’s early years coincided with a golden age of Bollywood cinema. Actors, writers, and directors like Raj Kapoor, actor, director, writer, and founder of a cinematic dynasty still prominent in Bollywood today, created films combining the harsh realities of rural and urban India with fantasy scenes of song and dance. (Dissanayake and Sahai,1988, 157-161) As the Chaplainesque Raj or Raju (meaning king or nation among other things) in his films Awara (The Vagabond, 1951) and Shri 420 (The Gentleman Cheat or Mr 420—a reference to the Indian penal code dealing with fraud— 1956), Kapoor sings and dances with the pavement dwellers, breaking free of the film’s linear narrative. They welcome him, a young man from the countryside, into their urban village, a shanty town on the street just outside the villain’s Art Deco residence. The snares, cruelty, poverty, and immorality of Bombay life alternate with elaborately designed and choreographed dream sequences. In these fantasy production numbers, Kapoor honours the music, dance, and imagery of Phalke’s devotionals, but he also equals, if not surpasses, Busby Berkeley’s Hollywood extravaganzas in the sensuality, monumental scale, and modern abstraction of his cinematic visons. (Starr, 2001, 77-78)

With partition into India and Pakistan, Phalke’s villagers were violently displaced. They lived suspended between two worlds, villages created on the pavements of the modern metropolis. Kapoor’s Raju symbolizes this partition and displacement in his very dress, wearing a western jacket with traditional loincloth, dhoti. And the Liberty Theatre, where films like Awara had their premieres, also combined the new space where Gandhi’s rural and Nehru’s modern India met, drawing on the stuccoed, small-scale buildings of traditional India as well as the technologies and streamlined forms of the modern world.

While Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh, the new capital city for Haryana and Punjab Nehru commissioned, may still be the face of modern Indian architecture in the West, Art Deco cinemas like the Eros and Liberty were another modernism created by the other. Yet they were not simply about the colour, ornament, and theatricality orthodox modernists so disdained in western examples of Art Deco. They represent parallel or indigenous modernity, ways of using and understanding modern ideas and influences from outside without sacrificing one’s own forms, values, traditions, and aspirations. (Larkin and Hosagrahar) Art Deco theatres like the Eros and Liberty paradoxically embraced and resisted western modernism. In the violent yet euphoric atmosphere of the thirties, forties, and fifties, these Art Deco cinemas were vibrant, complex, and defiant modern architectures designed by Indian architects for a people determined to recover their own pasts while charting their own futures.

Source:

Article published in “Everyday Modernisms and Urban Environment- articulating the playful and the ordinary in the city”, titled “THE OTHER AND THE OTHER MODERNISM: ART DECO PICTURE PALACES OF BOMBAY” by Professor Mary N. Woods, Department Of Architecture, Cornell University 143 E. Sibley Hall, Ithaca, New York 14853, USA

mnw5@cornell.edu

Click here to view “Liberty Cinema: The Showplace of the Nation”, a short film by Art Deco Mumbai Trust.