It is coated in layers of grime and dust, with sackcloth draped across its exterior, but the fading façade and Art Deco lines and curves of Liberty cinema speak of a bygone era of glamour at the talkies, and a sense of optimism and individuality in the heady days leading up to independence and beyond.

Along with Regal, New Empire, Eros and New Excelsior cinemas, Liberty constitutes the remainder of Mumbai’s Art Deco cinemas, which dominated the cinema-going scene from their inception in the mid-1930s onwards.

But now, faced with hurdles, including a dearth of new releases, as well as hefty entertainment taxes and competition from multiplexes, the survival of these structures, characterized by their geometrical shapes and vibrant colours, is hanging in the balance.

Regal cinema, the oldest among its peers and a Colaba landmark, has been forced to temporarily shut its doors in the face of mounting losses, while Metro cinema has been refurbished and converted into a multiplex. Conservation experts warn that the others are set to follow suit. This comes in the wake of the closures of the Strand and Aurora cinemas.

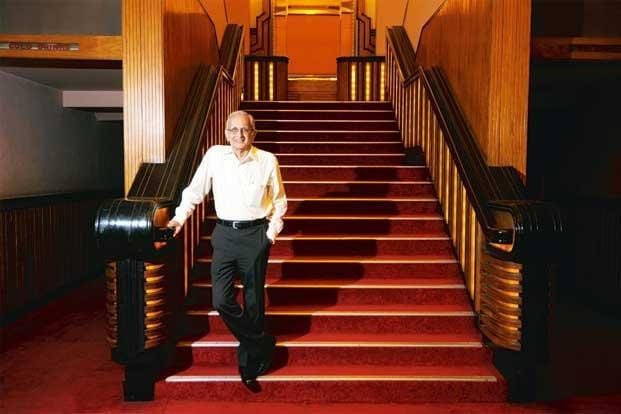

“This year has been a pretty bad year,” says Nazir Hoosein, owner of Liberty cinema in Churchgate, which was founded in 1947 by his father Habib, and named in honour of India’s independence. “We will stay open for as long as we can, but we are making losses. This industry is a chain, and a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. We have to work together, and every link has to make money because otherwise, it doesn’t work.”

In addition to contending with a revenue-sharing dispute between the multiplexes and production houses, which has seen all new cinematic releases being put on hold since 4 April, and before that a string of box office duds, Hoosein’s troubles are compounded by the entertainment tax that is levied by the state of Maharashtra at a punitive rate of 45% on single screen cinemas.

Currently, of the Rs 100 earned from every ticket sold, Rs 45 is immediately deducted for entertainment tax, and the remaining Rs 55 split between the cinema owner and the producer, leaving in the region of Rs 27 for the cinema owner to cover his costs.

“The single screens can’t survive, and instead the government has given a tax holiday to the multiplexes,” says Hoosein. “When the multiplexes came up, the government gave them a three-year tax holiday, and then they only had to pay 25% for the next two years. Cinemas have been a milch cow for the government and we have paid in crores over the year, but the situation is different now and it is so ridiculous to have this level of taxation. It’s payback times.”

Liberty, described as “an exquisite jewel box of rococo decoration enhanced by a coloured lighting scheme suggesting a fairyland far away from the bustle and tumult in the streets outside” by David Vinnels and Brent Skelly, authors of Bollywood Showplaces: Cinema Theatres in India, is often singled out as exceptional among its class.

However, the cinema has resorted to playing re-runs and regional language movies in the absence of new content, and costs about Rs. 9 lakh a month to run, with electricity bills making up about one-third of the total. Hoosein, who says that his monthly earnings from the 1,200-seat cinema vary dramatically and depend on how popular and successful the “product”, or film, is, supplements his income by renting out part of the building for office use.

Burge Cooper, owner of New Empire cinema, who doesn’t have a similar buffer against his operating losses, says the ability to maintain the old cinemas is “diminishing by the day” without new releases to entertain audiences with.

“There has to be some support for the old cinemas,” says Cooper, who cites entertainment tax and the absence of preferential rates for electricity as further debilitating factors. “We do not have the flexibility to cut occupancy by 50% like the multiplexes do. We are compelled to try to survive. These are very tough times. Shutting down is going to have to be a hard option to take if things do not change in the foreseeable future. But I hope things change and that product comes back into the market soon.”

Further, a clause that requires the owners to constantly maintain the presence of a cinema hall on the land acts as an additional bind on Hoosein and his fellow-cinema owners, who are unable to transfer the land for any other purpose.

“We can’t use the theatre for any other purpose,” says R.V. Vidhani, president of the Cinema Owners and Exhibitors Association of India. “Bombay is the birthplace of the cinema industry and now it is dying. I think it is very difficult for them to survive because it is not a level playing field. If there was an announcement that allowed cinemas to shut their doors, then I think that very day they would all close because they are all suffering heavy losses.”

Vidhani, who says that his efforts to lobby the government to reduce the tax rate and create an environment conducive to the survival of the Art Deco cinemas, have fallen on deaf ears, adds that: “Movies are for the masses and not the classes. Cinema is for the masses and it has survived for the masses, but now it is becoming inaccessible for them.”

A potential solution, regarded as controversial by city conservationists, is for a sale to the multiplex chains, as in the case of Metro. The cinema, originally built by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) and decorated in shades of red and pink, complete with a marble foyer and staircase, was bought by Reliance BIG Cinemas in 2005 and refurbished at great cost, including the restoration of the original interiors, before re-opening in 2006.

The need for an infrastructure to support the Art Deco cinemas in their battle against competition and to help maintain the structures is emphasised by Sharada Dwivedi, city historian and a member of the Mumbai Heritage Conservation Committee.

“I think there is a real danger that the Art Deco cinemas could go extinct,” warns Dwivedi, who co-authored Bombay Deco with architect Rahul Mehrotra. “Strand cinema closed down, the Aurora cinema has been closed for over two years, and it is unfortunate if they all go the Metro way. We have neglected our entire Art Deco heritage to the point where it might vanish. Neither the government nor local councils have any respect for heritage structures and I am concerned for the future of the other cinemas.”