The final stages of the Independence Movement coincided with the development of Bombay’s Backbay reclamation. This article explores the subtle, yet powerful, political statements made by Bombay’s Deco buildings, and details how Bombay Deco symbolises a lost rendition of India.

Certain years occupy more pages in history books than entire decades. These years stand out as critical junctures when an attempt is made to substitute an old, obsolete order with a new one. Turbulence and uncertainty reign supreme. In India’s long drawn out and illustrious history, 1929 was undoubtedly one year when the Indian story took a definite and irreversible turn. On 19 December 1929, The Indian National Congress passed the historic ‘Purna Swaraj’ resolution.(i) Until then, Indian nationalists were content with India obtaining the status of a dominion under the British Crown, an arrangement conferred upon white-settler colonies like Canada, South Africa, and New Zealand. However, despite repeatedly promising autonomy to Indian leaders, the British Administration made no mention of any timeline, and regularly delayed further substantive negotiations.(ii) The Purna Swaraj resolution finally marked an end to India’s long patience towards Britain’s false promises. This short, 750 word document called for a permanent severing of ties with the Empire, and demanded complete and unconditional independence from Britain.(iii) With the adoption of this resolution in Lahore, India entered uncharted territory. She was finally flirting with the idea of becoming a nation-state in a turbulent world. She was confident enough to entirely erase Britain from her political landscape, and felt ready to adopt an ardently purist and nationalistic understanding of herself.

Adopting ceremonial declarations like the Purna Swaraj resolution is simply one step in a long chain of events that marks a country’s transition from a supressed colony to a free nation. For India to emerge as a respected member of the international community, she had to go through the profound process of nation-building. Indian leaders had to present a vision of what India would look like upon independence to roughly 300 million people who lived in her territory.

“The idea of what it meant to be Indian had to be constructed, and put in front of people for them to be a part of this national project.”

The Indian Dream had to be fleshed out, and, as Jawaharlal Nehru’s book framed it later, India had to be ‘discovered.’ However, India’s seemingly permanent discomfort with reaching a consensus was evident even in her attempt to become a nation-state. Multiple ideas of India were floating in the public domain in the few decades before independence, and these ideas regularly contested one another.

On one hand, Nehru envisioned India as a secular, plural, and modern democracy. A staunch Socialist, Nehru wanted India to have a strong central state that would act as a vanguard of industrial and social progress. The socialist state’s primary goal would be to keep destructive imperial and capitalist forces at bay. Nehru’s India would be staunchly self-reliant and modern, and a benevolent government would occupy a central role in independent India’s transition to modernity. On the other hand, Gandhi wanted India to go back to its spiritual roots and preserve its agrarian and rural fabric. Industrialisation, urbanisation, and modernity had a limited role to play in Gandhi’s India. This was reflected in Gandhi’s complex relationship with Bombay. After returning from South Africa, he disembarked in India’s financial powerhouse, and remarked to his nephew, “I don’t like Bombay. I see here all the shortcomings of London but find none of its amenities.”(iv)

Gandhi critiqued urban societies like Bombay for their suppression of masses, and squalid poverty and dirt.(v) By the 1930s, Gandhi and Nehru’s contrasting aspirations of India would emerge as dominant templates for the new nation-state.

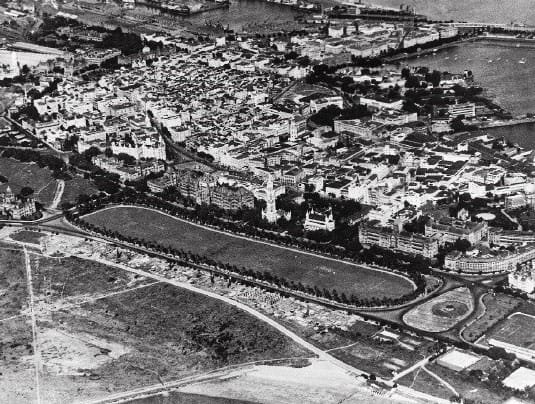

1929 was also as an important year for India’s first city. The controversial Backbay Reclamation Scheme was half-heartedly completed that year, and 439.6 acres of reclaimed land became available for building at Churchgate, Colaba, and Backbay.(vi) Over two hundred years, Bombay had undergone multiple rounds of urban expansion that had repeatedly altered the character of the city. In the 18th century, the building and consolidation of the Fort marked the emergence of Bombay as a global trading post. While, the removal of these ramparts in 1867 allowed the city to sprawl, and led to the rise of Bombay as a full-fledged commercial and industrial city.(vii) Each definite round of urban expansion had overhauled the character of Bombay, and the completion of the Backbay reclamation scheme yielded yet another opportunity for the city to reinvent herself.

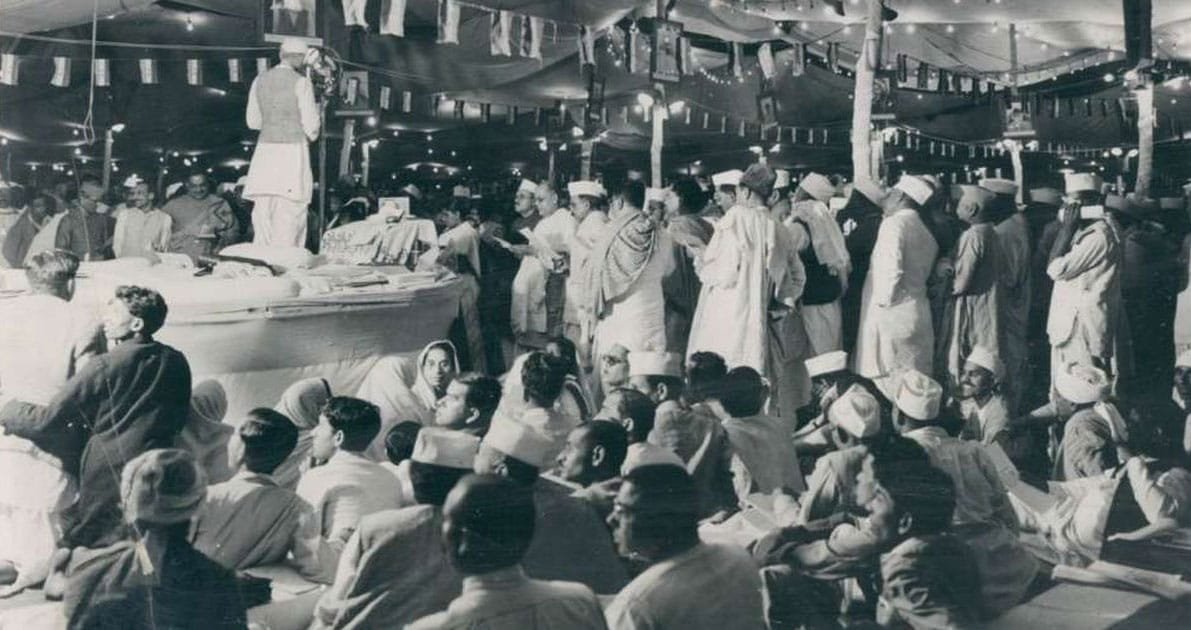

However, this time around, Bombay was not the island it used to be, and had to reconcile its aspirations with the aspirations of an emerging Indian nation. In India’s long and troubled history with the British Empire, Bombay had somewhat been an odd ball. The city was a unique cooperative project sustained by an alliance between the British and several Indian communities.(viii) Because of special concessions given by British Governors, Indians in the city occupied enviable positions in industry, government, and professional services which somewhat diluted the colonial systems of oppression prevalent in other parts of the country.(ix) This coupled with the physical separation of Bombay from the Indian mainland led to a historical trajectory that was markedly different from the rest of the country. The Anglo-Maratha wars and the Sepoy Uprising of 1857 hardly touched Bombay. However, by the 1930s, the city emerged as the nerve centre of the Indian Independence movement. The Taj Mahal Hotel started hosting vital meetings of the Indian Chamber of Princes(x), while the Indian National Congress repeatedly held its sessions in the city. Bombay’s textile mills became a vital flashpoint during the Swadeshi movement, while the city’s coastline was a site of active protest during the Salt Satyagraha.(xi)

“Steadily, the once different trajectories of Bombay and India were fused by the 1930s, and the city was compelled to imagine its position in a soon to be independent India.”

Architecture is hardly ever a mute spectator to these underlying tensions. Michael Windover claims that the consumption and production of any image became an act of great political significance as the independence movement gained momentum in the 1930s.(xii) Because of a splendid coincidence brought about in 1929, Bombay seemed poised to use her newly reclaimed land to jump into the debate on not only her own, but also India’s future. As Bombay and India drifted towards each other in the decades leading up to independence, the city’s latest opportunity for urban expansion was going to be profoundly influenced by India’s attempts to discover and define herself. But importantly, what was Bombay’s take going to be?

India’s rather bold turn towards Purna Swaraj surprisingly made Bombay’s diverse elite nervous. Elites are usually sceptical of rapid political change as more often than not their status is intimately dependent on the preservation of the current order. Nowhere was this more evident in India than in Bombay. Bombay’s elite comprised of a cosmopolitan group of people like rulers of Princely States, Parsi industrialists, and professionals cutting all sects. As outlined by Naresh Fernandes, this elite class was artificially assembled over time by British Governors who gave special concessions to trading castes and ethnic minorities to woo them into this new commercial centre.(xiii) As a result, Bombay’s economic and political fortunes appeared to be intricately linked to its ties with the empire, and the emerging Gandhian and Nehruvian visions of India seemed poised to permanently disrupt this. Nehru’s unwavering faith in socialism and self-reliance induced anxiety in a city that had historically depended on free market capitalism and free trade, while Gandhi’s cry to come back to the villages challenged Bombay’s urban and industrial sensibilities.

However, this does not automatically suggest that Bombay was opposed to the idea of independence. The city was in fact the birthplace of the Indian National Congress, and Bombay’s elites were the largest financiers of Gandhi’s crusade against British injustices.(xiv) But because of the city’s unique history and economic linkages, Bombay’s elite communities like the Parsis favoured a gradual shift towards political autonomy over rapid, unconditional independence. When the first session of the Indian National Congress met on 28 December 1885 in Bombay, the proposals adopted were incredibly moderate.(xv) However, the Purna Swaraj declaration symbolised a sharp departure from Bombay’s moderation towards purist nationalism. Bombay’s cautious elites who had a lot to lose from severing ties with Britain were unnerved by this bold and rapid outburst of emotions. What elites in India’s premier urban centre wanted instead was an expression of a middle ground. A middle ground that could effectively accommodate not only their own interests, but also the now popular idea of an entirely sovereign India.

The impressive collection of Art Deco buildings that eventually sprung up on those 439.6 acres stunningly embody this middle ground through their unique architectural eclecticism and materials. In this process of discovering a middle ground, Bombay’s elite unknowingly put forward an entirely new rendition of independent India. An India that was fundamentally different from its dominant Nehruvian and Gandhian interpretations. Bombay’s India would reject Gandhi’s rural austerity, and develop a taste for urban public culture, flamboyance and flair. In line with Nehru’s dream, Bombay’s India would be modern, progressive, industrial, and urban. However, this transformation would not be spearheaded by a benevolent socialist government or defined by principles like self-reliance. Instead, the burden of India’s transformation would remain on the backs of private individuals like the city’s enterprising industrialists. The city’s version of India would not be self-reliant or disconnected, but would confidently import and reform global ideas.

An academic expert on the social implications of Art Deco architecture, Michael Windover argues that Bombay’s apparent obsession with this style during the independence movement should not be simplistically understood as the city’s desire to appear Western or American.(xvi) Instead, ‘Bombay Deco’ is uniquely indigenous in style and character, and symbolises a rebellious attempt by the city to wrest control of the cityscape from British hands. Interestingly, a large majority of these buildings were not commissioned by the colonial state, but were independently built by Indian industrial elites like Framji Sidhwa, Shiavax Cambata, and K.A. Kooka.(xvii) A more admirable representation of Bombay’s ambition of being independent is the role of Indian architects in not only importing, but also reforming this style to suit Indian tastes and sensibilities. The Deco buildings that line Marine Drive and the western flank of Oval Maidan were the first to be designed by a new generation of Indian architects like Gajanan Mhatre, Sohrabji Bhedwar, and P.C. Dastur who studied in Britain or newly established schools in the city like the J.J School of Art and Architecture. This new generation of Indian architects gave Bombay Deco its remarkable indigenous flair through tropical motifs, Indian imagery on bas-reliefs, projections above windows to block sunlight, and curvilinear balconies.

“In tune with the rest of the nation in the 1930s, Bombay was clawing back its independence from Britain, and the city’s elites’ dream of an independent India was projected on an unlikely screen: its new block of Deco buildings.”

While Bombay dreamt of an independent India, its version had a limited role for Nehru’s socialist state. Instead, Bombay’s top brass had historically placed its faith in free market led trade, commerce, and industry. The city’s widely chronicled prosperity was defined by these principles, and Bombay’s elites were rather comfortable with and used to the idea of a limited state. This is manifested in the extreme paucity of state buildings in the Art Deco ensemble of Bombay. A large proportion of Art Deco buildings were instead dedicated to residential, commercial, and recreational purposes. In these respects, Bombay’s Deco ensemble stands in stark contrast to its stellar collection of Victorian Gothic buildings. Bombay’s magnificent gothic structures like the Old Secretariat building and the High Court not only housed various functions of the imperial state, but also symbolised the dominance of an alien power over the city. While on the opposite side of the Oval Maidan, the upcoming Deco structures were more humble in demeanour. They did not intend on explicitly celebrating any institution of power, but were instead keen on creating an urban fabric that could successfully sustain a commercial, consumerist, and capitalist society. When Bombay imagined India’s future in the 1930s, the city wanted the nation to follow its suit. Bombay’s affinity to private enterprise and limited interference had catalysed its transformation from a swampy archipelago to the second largest city in the British Empire. Through their Art Deco buildings, Bombay’s elites seemed to have endorsed a private and consumerist society over a socialist one.

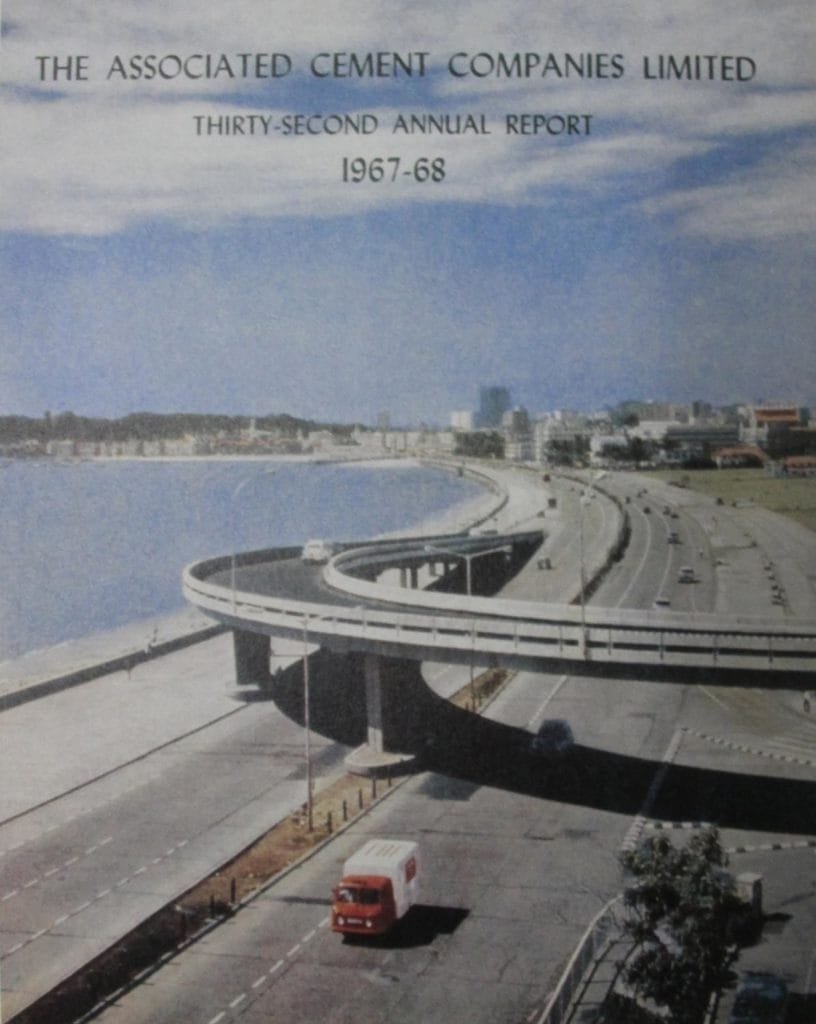

The constituent elements of Bombay’s dream were cohesively represented in the city’s search for a new material. Art Deco was a decisively modern architectural style, and it wholeheartedly drew inspiration from prevalent trends in science, technology, and industry. Art Deco marked a decisive break from the several revivalist styles of the 19th century, and aimed to unequivocally symbolise the arrival of ‘modernity.’ In its quest to appear modern, Art Deco buildings often extensively used new materials like steel frames and reinforced concrete. Bombay’s upcoming Art Deco ensemble became one of the first large scale projects in India to extensively use reinforced concrete for construction. And incidentally, Bombay’s reinforced cement concrete mirrored its vision of India. In addition to being modern, it was indigenous, and was spearheaded by private enterprise.

The 1930s witnessed the unprecedented proliferation of cement companies privately owned and run by Indians. By the end of the 1920s, there were cement manufacturing companies in Wah, Lahore, Delhi, Banmor, Lucknow, Lakheri, Karachi, Kymore, Katni, Mehgaon, Porbandar, Nagpur, Calcutta, Bombay, Shahbad and Madras, each equipped with modern plants making Portland Cement that exceeded the requirements of the British Standard Specification.(xviii)

“Cement suddenly became an ‘Indian’ material, and using Indian cement in construction projects became a subtle political statement against the British as it showcased India’s ability to independently industrialise.”

It thereby attacked one of the most crucial myths justifying British rule in India: the myth that the country would remain backward without British wisdom. Furthermore, private cement companies such as Dalmiya Cements and the Concrete Association of India ran well organised publicity campaigns to push their new magic material into Indian cities.(xix) Through annual publications like the ‘The Modern House in India,’ Cement Marketing Companies of India widely disseminated information about how a confluence of Art Deco architecture and reinforced concrete could usher in a new era of modernity.(xx) Importantly, these publications played a pivotal role in circulating images of Bombay’s upcoming Deco buildings throughout India, and the city’s newest district subsequently emerged as a symbol of this new rendition of India.

However, Bombay Deco’s most powerful contribution to the future of the Indian nation was its strong and undeterred cosmopolitanism. Despite being categorised as a markedly Western Style, Art Deco wholeheartedly drew inspiration from local settings to produce unique symbols and designs. This global localism defined Art Deco, and is visible in some of its most prominent features like ziggurats and pyramids. Bombay Deco emulated this eclecticism through the use of diverse motifs that paid homage to the city’s different ethnic and religious groups. The city’s deco buildings beautifully combine western styles with prevalent Hindu, Islamic, and Zoroastrian symbols to commemorate the city and the nation’s diverse history. Through this confluence of styles, Bombay’s Art Deco buildings preached a subtle message about peaceful coexistence in an India that was getting increasingly anxious about its diversity in the two decades before independence.

“Although Art Deco in Bombay explicitly expressed nationalist sentiments through its materials and design, it simultaneously resisted an overtly purist and homogenous reading of the Indian nation.”

Art Deco Architecture’s role in advancing a new iteration of independent India, one that contested Nehruvian and Gandhian notions, possibly explains Deco’s rather sudden decline after independence. In an interview with Atul Kumar, founder of Art Deco Mumbai, Abha Narain Lambah made a remarkable claim that Bombay’s Art Deco architecture facilitated the rise of Modernism in Chandigarh.(xxi) The engineers and artisans who experimented with plaster and reinforced concrete for the first time in Backbay carried their expertise with them to Nehru’s dream capital in the north. However, by the time Chandigarh’s core was completed, Art Deco had already become a relic of a bygone era. After independence and Gandhi’s withdrawal from electoral politics, Jawaharlal Nehru was able to cement his control over the newly independent country. This gave the visionary Prime Minister the ability to finally implement his version of India: a modern nation with an omnipresent socialist state.

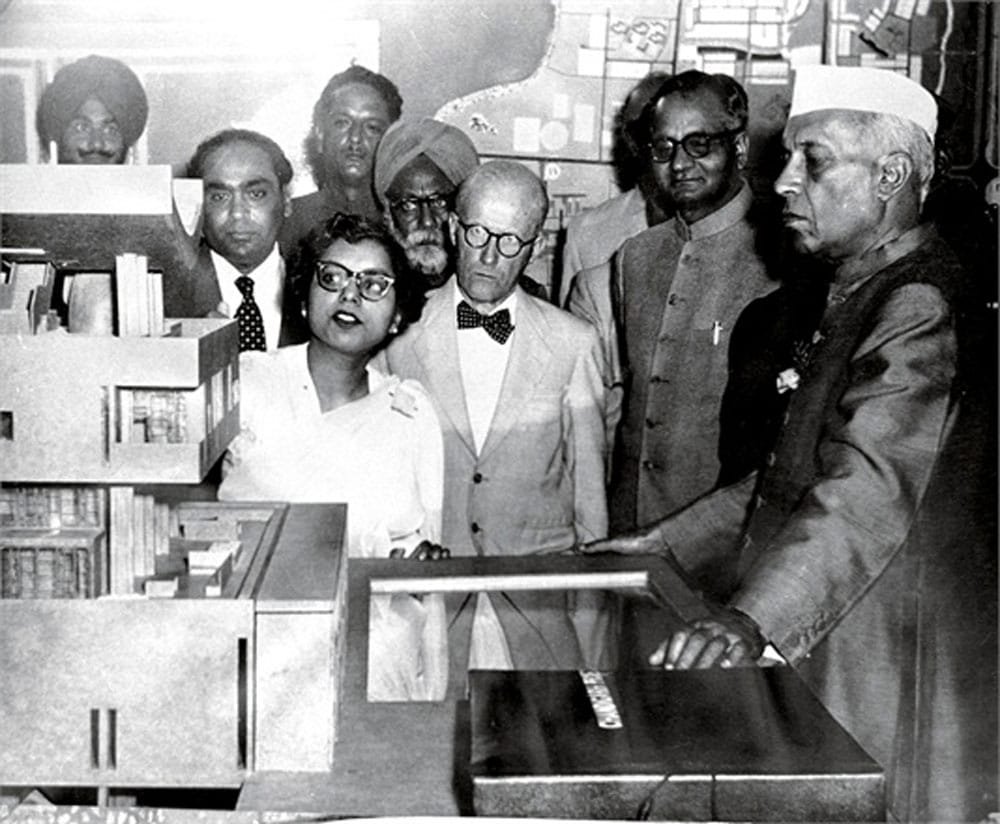

Nowhere was this more evident than the streets of Chandigarh. The Prime Minister’s pet project, Chandigarh was a model of what Nehru wanted India to be. Visiting this new project in 1952, Nehru remarked that Chandigarh would be “a new town, symbolic of the freedom of India, unfettered by the traditions of the past.”(xxii) Like the nation itself, Le Corbusier’s imposing and sober government buildings emerged as the irreplaceable core of the city. Unlike Bombay’s Deco district, Chandigarh was not spearheaded by private entrepreneurs, but by a powerful central state.

“Chandigarh’s Modernist architecture thereby marked Nehru’s ultimate monopoly over India’s nation building process, and commemorated the subtle displacement of Bombay’s vision of India.”

Bombay Deco was decisively civilian, and Nehru’ affinity to socialist sobriety significantly narrowed the space for the kind of social statements made by Art Deco buildings.

In 1929, India embarked on an ambitious mission. She staked a claim to national sovereignty, and was passionately searching for a way to get there. Nations are not just bounded territories with a government and a military. Instead, nations are ideas: ideas about what it means to be a part of a community of people. Nations are exceptionally fluid, and subject to constant scrutiny. While India was discovering herself in the 1930s, multiple visions of the nation were put forward. Gandhi’s agrarian and rural austerity clashed with Nehru’s socialist modernism, while Nehru’s socialist modernism challenged fringe religious fundamentalism. Amidst this chaos, Bombay’s elites were trying to squeeze themselves in the national debate. India’s first city wanted the rest of the nation to follow her suit, and dreamt of an India that was independent, modern, capitalist, and cosmopolitan. The city’s elite ingeniously employed 439.6 acres of reclaimed land and Art Deco to project their aspirations of an independent India. Bombay’s glorious Art Deco district is thereby a vivid reflection of what the city wanted India to be. In this process, the district is a tangible monument to the city’s chronicled position of being India’s factory of dreams and visions.

Chirayu Baral for Art Deco Mumbai

Chirayu is deeply passionate about Mumbai’s overlapping architectural styles. He is a Charles A. Dana Scholar for the Class of 2019, at Bates College, USA where he is a final year student obtaining his Bachelor of Arts Degree with a Double Major in Economics & Politics and a Minor in History.