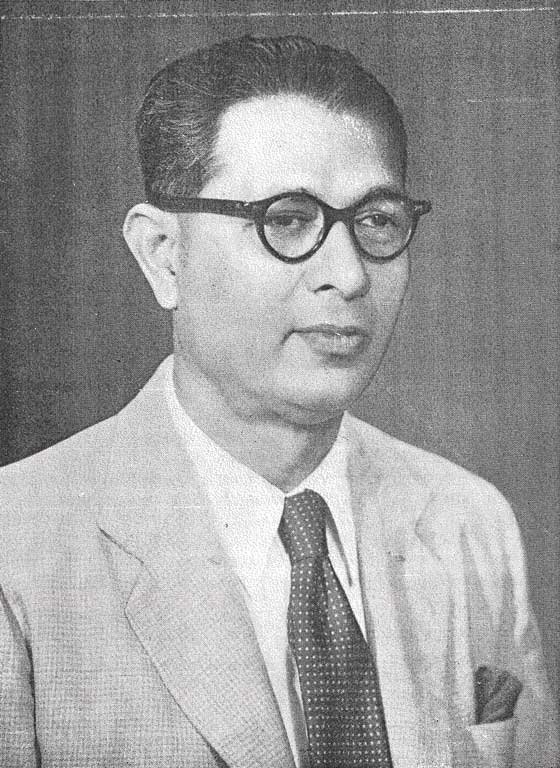

Bombay’s Art Deco era coincided with one of the most critical periods in its urban development. The city’s “building boom”, facilitated by the newly introduced material RCC (reinforced cement concrete), witnessed intense building activity and rapid northward expansion of the city. One of the personalities who played an instrumental role in shaping the built environment during this era, was the architect Gajanan Baburao Mhatre.

By the early 20th century, Bombay was a thriving port city and commercial centre with a steady influx of migrants. Unprecedented demand for housing on account of this influx, prompted a series of planning initiatives by the City Improvement Trust, of which planned precincts were most significant. It was during this era of planned precincts when the apartment block emerged as a typology of housing. The city’s earliest apartment blocks have often been mistakenly attributed to foreign architects by local citizens, when in fact it was the first generation of Indian architects responsible for their development. A significant number of these apartment buildings from the Deco era can be credited to G.B. Mhatre, whose vast body of work also included a variety of typologies from fuel stations to commercial buildings and places of worship.

G. B. Mhatre’s work spanned the period between 1931 and 1970. He began his practice at the dawn of Bombay’s Art Deco movement, in an age when there was limited media attention to architecture and professionals were known only by their success, usually commercial. G.B. Mhatre’s contribution, although important, went largely unrecognised. His reticent nature and the prevailing ethics of the profession, which did not look kindly at publicity, did not help bring him the fame he deserved. However, those who came across him professionally acknowledged him as a gifted architect.[1]

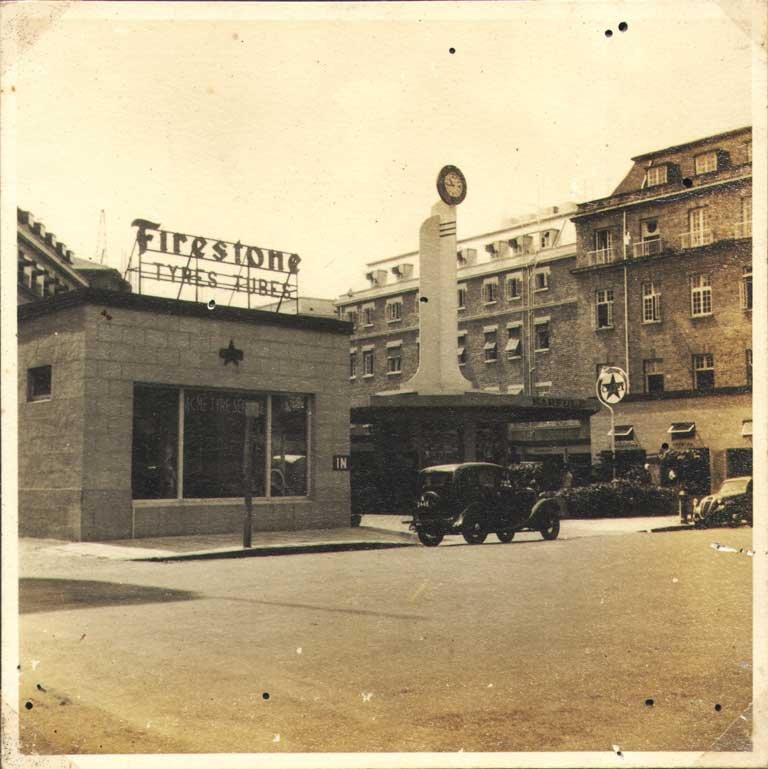

Born in 1902 in a family of modest means, Mhatre spent his formative years in Sir JJ School of Art. He was influenced by his teacher Claude Batley, who besides his role as an educationist, was known for being a founding partner of Gregson, Batley & King, one of the most prominent architectural firms of the 20th century in India. Batley was sensitive to Indian architecture and uniquely introduced an approach to modernism through an understanding of traditional architecture. G.B. Mhatre introspected on the past and absorbed from the deep study of Indian architecture, particularly the Muslim architecture of Gujarat.[2] He left for England in 1928 to qualify for the associateship of RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects). He supplemented his education with part time work in London, where he was exposed to design ideologies prevailing in western practices at the time. He came back in 1931 and joined the firm “Poonager and Bilimoria”.

An engineering firm, Poonager & Bilimoria recognised Mhatre’s architectural abilities, retaining him to design buildings in all respects, and also oversee the execution of architectural details on site.[3] Sunshine at Oval Maidan (1936), and Rao House, Matunga (1937) are examples of notable works designed and executed by G.B. Mhatre during his association with Poonager & Bilimoria.

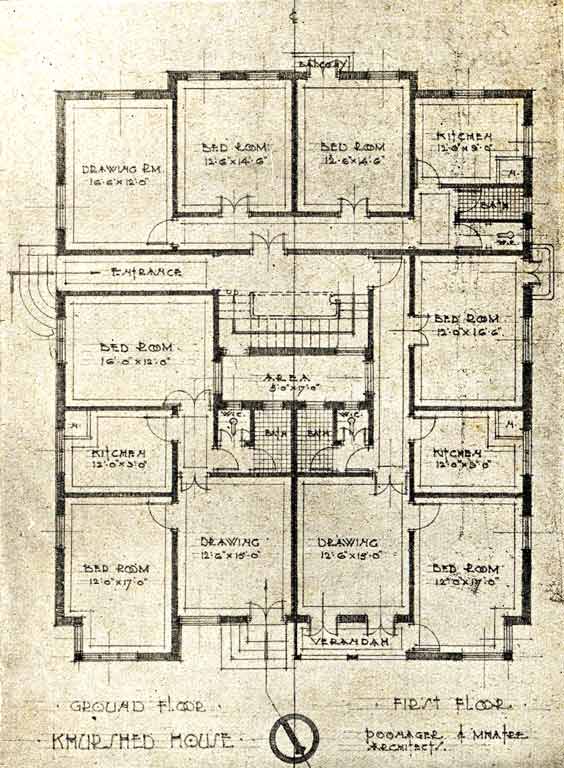

Khurshed House, Dadar Parsi Colony – an early apartment building designed by Mhatre, with the work credited to ‘Poonager & Mhatre Architects’. Source: Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects, July 1934

Rao House is a unique Art Deco building in Matunga, with its facade rounding at the street corner. A square shaped staircase tower set at a 45 degree angle to the facade serves as a focal point. Collonaded verandahs with sloping chajjas, quintessential to Bombay’s Deco architecture in response to the local climate, wrap the building’s curved facade. This project, like many others designed by Mhatre, was signed as ‘Poonager and Mhatre’ in its later stage.

G.B. Mhatre’s work in association with Poonager & Bilimoria formed the bulk of his practice in the 1930s. During this time, he also took on projects in the capacity of a consulting architect with various firms. His skill and attention to detail was well known in the architecture community. He was often asked to design only the facade of a building, as in the case of Court View, Oval Maidan. Among his most significant projects as a consulting architect was Empress Court and Sorab Mansion with Contractor & Kanga, and Soona Mahal with Suvernpatki & Vora. Although he was largely responsible for the designs of these buildings, credit often went to the firm that was commissioned. The absence of his signature on drawing sheets for a large volume of work, prompted Claude Batley to call him a ‘shadow architect’.[4]

During correspondence with Russi K. Bana of the firm Merwanji, Bana & Co. and the editor of the October 1937 JIIA published in the journal, Mhatre expressed his views on the role of a ‘shadow architect’ – “…it is not correct to say that the Bachelors of Engineering alone get their designs retouched by the so called “Shadow Architects” but some of the members of the Institute-themselves full fledged Architects-have to depend upon such assistance. I do not see what is wrong in the practice if it leads to an improvement in the design of their buildings. It also benefits the public at large and demonstrates to them the advantages of employing competent Architects. Ultimately it is the work that counts, and the profession and public in Bombay are sufficiently intelligent to give the credit where it belongs.”

In April 1938, G.B. Mhatre ended his formal association with Poonager, Bilimoria & Co.[5] Thereafter, he began his own practice “Architectural Studio” along with the architect K. A. Parelkar and interior decorator M. A. Mirza. Notable works of Architectural Studio include Karfule at Ballard Estate (1938) and Marble Arch on Pedder road (1942).

G.B. Mhatre’s practice is closely linked with the emergence of architecture which in the 1930’s-1950’s was significantly different from what preceded it. This was in part caused by the sudden need for housing in a growing city. The demand was met by massive public work in newly reclaimed areas of the city and suburbs and in order to decongest the city, new areas were opened up for development. Among these were Marine Drive, Oval reclamations and Dadar-Matunga. The newer development showcased the concern for the urban design issues and specific bylaws were evolved in each residential district related to setbacks, heights, and elevation controls. However, these strict byelaws by the City Improvement Trust left little scope for variation in plan arrangements and limited architects to the treatment of the external facade, design of the stairs, entrance hall, and lettering to the exterior. These elements often showcased the exuberance of the Art Deco style.

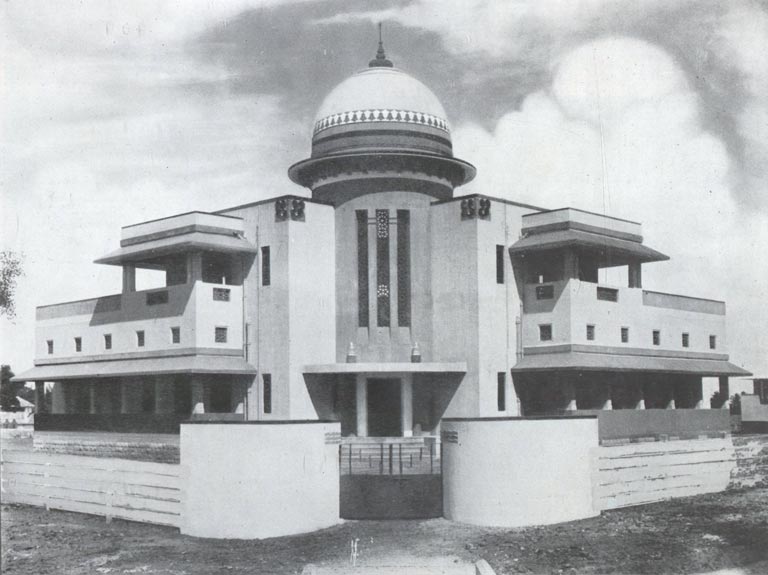

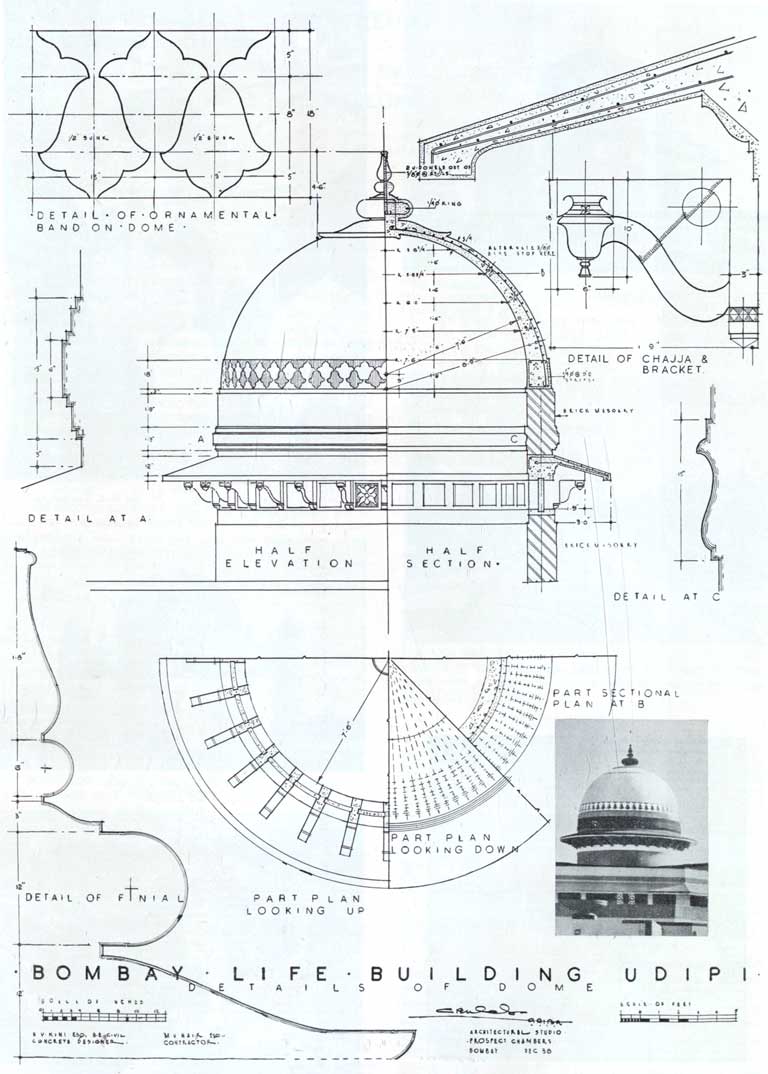

Bombay Life Building, Udipi (Left) and detail drawings of its RCC dome.

Source: Journal of IIA, July 1939

The influence of traditional Indo-Islamic architecture is evident in his design for the Bombay Life Building in Udipi, Karnataka, built in 1937. The building is a striking contrast to his work in Bombay and adapts to its rural surroundings. His ingenuity in designing a traditional dome with modern construction materials is showcased in his detail drawings published in the Journal of IIA.

One of many religious buildings designed by Mhatre was the Datta temple in Prabhadevi, built in 1941. This modest temple was designed within the principles of traditional Hindu temple design but with modernist sensibilities, while incorporating traditional elements like the jali, chajjas, and a dome.

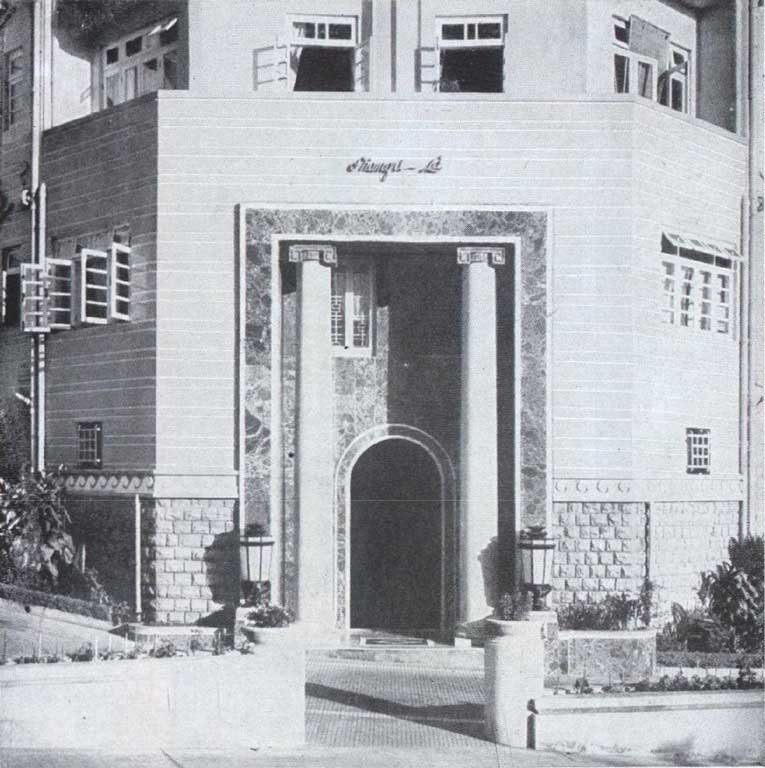

One of his prominent apartment buildings, Shangri-La at Cumbala Hill, is distinctive for its symmetrical massing, with streamlined balconies and curvilinear bay windows. The highlight of the building is its entrance, positioned on the facade’s central axis. The luxurious marble clad entrance is in tune with the overall design of this Deco marvel. The entrance is flanked by a pair of classical columns clad in Malad stone. G.B. Mhatre gave special attention to the treatment of entrances for the buildings he designed, ensuring they appeared inviting and appealing. He believed that these entrances leave a lasting impression on visitors and in the case of apartment buildings, encouraged prospective tenants to rent flats.[7]

The evolution of his style into a more restrained and functional yet elegant modernism is evident in his work from the ‘40s onwards. Marble Arch on Pedder road, built in 1942, has a restrained modernist aesthetic with the facade slightly curving away from the road. A similar design sensibility can be noticed in several bungalows he designed for clients in Bombay and Pune.

United Bank of India, on Pherozeshah Mehta road (1958) is representative of Mhatre’s work and design style towards the twilight of his career. In contrast to his works during the Deco era, this building is characterized by its minimal, modernist facade clad in travertine, with conspicuous vertical fins. Bronze panels are visible on the spandrels between the recessed windows. The building’s entrance is recessed into the corner, a feature also seen in some of his previous works, like Marble Arch.

Apart from being a prolific architect with an eclectic style, Mhatre was also an educator and a member of educational boards such as the RIBA Board of Examiners in India and the Architectural Board of the Bombay University.[8] He was a Visiting Lecturer in the Architectural Section of the J.J. School of Art, and ran a private school, the Architectural Academy, with fellow architect Yahya C. Merchant. Late Kamu Iyer, who was his student at the J.J. School recalled that he would constantly repeat one mantra to his students: “A design is only worth the paper it is drawn on unless you know how it is built.”[9]

Mhatre was actively involved as a member of the Indian Institute of Architects (IIA), and was selected as its President twice in his career, from 1955-57. In his Presidential address, he advocated training the architect in administration and in taking up “responsible posts as Consulting Architects” as part of their architectural education.[10] His office acquired the atmosphere of an institution over time, seeing the likes of bright students from places as far as Hyderabad and Sri Lanka, including the pioneering Sri Lankan architect Minnette de Silva, who was once the only woman student in his academy.[11] Mhatre’s legacy includes his wider contribution as a member of various committees, from city planning, several IIA committees to architectural educational boards, etc. He advocated greater utilisation of Indian architects’ services in the planning of townships, of industrial developments, or of technical education, and appealed for the Indian architect to be given their “rightful place” in the Second Five Year Plan.[12] He represented the IIA in the governmental committee, the Floor Space Indices Committee, along with architect S. H. Parelkar.[13] Incidentally, both architects belonged to the Somvanshi Kshatriya Pathare (SKP) community, one of the earliest migrant communities of Mumbai who specialised in carpentry, architecture and construction.[14] He died in 1973, leaving behind an indelible mark on the city and its tangible and intangible landscape.

(Originally published on June 23, 2017. Revised September 14, 2021.)