Introduction

From the imperial structures of the British Raj that dominate its core to the temples and mosques that dot the city, the history of Bombay is written into its architecture, each era surviving in a distinct architectural style. At the beginning of the twentieth century, dual worlds of cinema and finance emerged amidst this urban narrative, becoming indispensable facets of Bombay’s identity. During the interwar years, both industries would find their architectural expression in the Art Deco style.

At its zenith in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Art Deco became a worldwide symbol of luxury and modernity, representing the very qualities that an increasingly restless set of Indians aspired towards. At the moment of its introduction in the subcontinent, Art Deco was seen as a simultaneously Western and universal style: Western in its geographic origins but universal in its wide-ranging visual inventory and eventual ubiquity. Its ability to occupy both these categories made the style an appealing choice for aspirational Indians. On the one hand, the eclectic motifs of Art Deco made it easier to inflect buildings with varying degrees of Indian iconography.[1] On the other, Art Deco’s lingering associations with Europe and the United States allowed its Indian strain to benefit from the hegemonic status of Western culture.

Beginning in the mid-1930s, local architects actively began to use Art Deco. They modified the style in response to an Indian cultural and geographic context, resulting in a formal mixture of foreign and regional design. Although Art Deco’s curvilinear geometry, setback volumes, and nautical motifs were often still visible, specific climatic and urban conditions prompted architects to adjust its distinct spatial compositions and to commission bas-reliefs depicting mythological Indian imagery. In its application in Bombay, the symbolism of the new architecture straddled two opposing political discourses, expressing neither a reverence for the colonizing world nor a total return to local roots.

Swadeshi Enterprise in the Fort District

Between 1935 and 1941 a cluster of Art Deco insurance buildings was constructed in the heart of the Fort district, the historic core of the city. With their relatively uniform massing and stone cladding, these offices were considered more “restrained” translations of the style.[2] Embodying a “more muted Modernism”[3] contingent on climate, new building codes, and the financial institutions they housed, these structures suggest a more intricate level of cultural negotiation than that of the opulent Art Deco cinemas nearby. This is evident not only in choices of material and ornament—protective awnings, heavy stonework, and sculptural reliefs are some examples—but also in the people involved in their creation—Indian industrialists, architects, and designers looking to establish reputations at par with their colonial counterparts. Jointly considering the architectural approaches of these agents, their motives, and the colonial mechanisms that undergird them, one finds that the Art Deco architecture of Bombay’s insurance companies was a more precise localisation of the style, exploiting the imagined cultural divide between India and the West by co-opting a foreign design movement—and its entailing connotations of modernity—to express the idea of India as a modern nation state.[4]

The sudden popularity of Art Deco during the interwar years came on the heels of a remarkable surge in the number of insurance companies founded since the turn of the century. Most of these were companies with Indian founders and many had names that explicitly suggested pride in a nation still developing its sovereign conscience: United India Insurance, New India Assurance, and the Hindustan Cooperative Insurance Company are some examples.[5] The Lakshmi Insurance Company drew from Hindu mythology by turning Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and good fortune, into an auspicious brand, while the Swadeshi Life Insurance company alluded to an influential contemporary political crusade.

One reason behind the Indian insurance boom might have been the discriminatory nature of older British insurance firms. Foreign businesses that opened branches in the colony tended to charge native customers higher rates for services or refused to cover them altogether. In response, the Indian insurance sector saw rapid growth during the interwar years; 176 new companies were founded between 1929 and 1939 alone.[6] The homegrown industry had its origins entangled in colonial injustice and thus harnessed the political rhetoric of the swadeshi movement in an attempt to reverse these inequalities. In seeking to provide Indian customers with services they had been denied, the insurance firms that gained footing in the 1930s had business agendas partly influenced by aspirations for individual and national autonomy. It was perhaps this exclusion from the financial system—and the desire to subvert it—that made Indian insurance directors receptive to the Art Deco style as a vehicle of self-legitimation.

This call to be self-sufficient—to be swadeshi—permeated across commercial sectors, becoming the raison d’être for much of Indian insurance. The reputations and political roles of the financiers further implied the patriotic underpinnings of the insurance sector.[7] Many of these native entrepreneurs identified with the freshness of Art Deco and commissioned their offices in the new style.[8] The swadeshi leanings of the insurance firms extended to the architects they contracted as well—all of the Art Deco offices built in the late 1930s were designed by local Indian practices such as Master, Sathe & Bhuta, Iyengar & Menzies, Kora & Bhat, and Mistry & Bhedwar.[9]

When these local architects began building in the style during the mid-1930s, most of their projects were clustered on recently-opened avenues in the Fort district and newly-reclaimed land around it. Significantly, this location compelled the new architecture’s engagement with pre-existing colonial conditions—Fort has long been the “image center” of the city, where spurts of building activity have resulted in a distinct architectural richness.[10] Not only were the insurance offices all located in Fort, almost all of them were constructed opposite and adjacent to each other along the newly-opened Sir Pherozeshah Mehta Road. Part of the municipal Hornby-Ballard Improvement Scheme, the road was created in 1928 to serve as a connective artery between the old economic region within Fort and a newly created business locale, the Ballard Estate. With this scheme, the City Improvement Trust also made over sixty plots of formerly state-owned land available for private development. But a 1938 Times of India report details the street’s initial unpopularity: “the breach made in the worst part of the Fort area was unsightly; some dilapidated old structures were exposed by the clearance, and there was little traffic on the new road though it was a short cut to the centre of the city from Ballard Pier.”[11]

The fact that Indian industrialists still chose to build on the unappealing road echoes a familiar logic—it allowed them to take advantage of inexpensive, unwanted land while still benefitting from the cultural prestige of Fort. But by 1937, the reputation of the street had vastly improved.[12] The addition of each new office engendered a public awareness of a newly-forming urban image. The City Improvement Trust’s introduction of building stipulations further entailed a uniform appearance along the avenue, which included adherence to site footprints and height limits of seventy feet. But it was these restrictions that made Art Deco an advantageous style for the architects tasked with filling the sites. Because the building regulations precluded architectural designs that involved dramatic massing or height variation, Indian architects channelled their creative expression into Art Deco’s ornamental vocabulary.[13] This resulted in elaborate bas-reliefs, vertical ribbing, and stylized names that decorated many of the office frontages.

As a set, the insurance architecture stood in contrast to the older commercial structures in the area, making a collective assertion about the economic future of the city and in whose hands this future belonged. The architecture of the nearby British-owned commercial offices tended more towards historicist colonial design than a radically modern style. As if in response, some of the Indian insurance offices imitated Classical orders through Deco design: the architects of the New India Assurance building replaced the capitals of its pillars with reliefs depicting native figures.

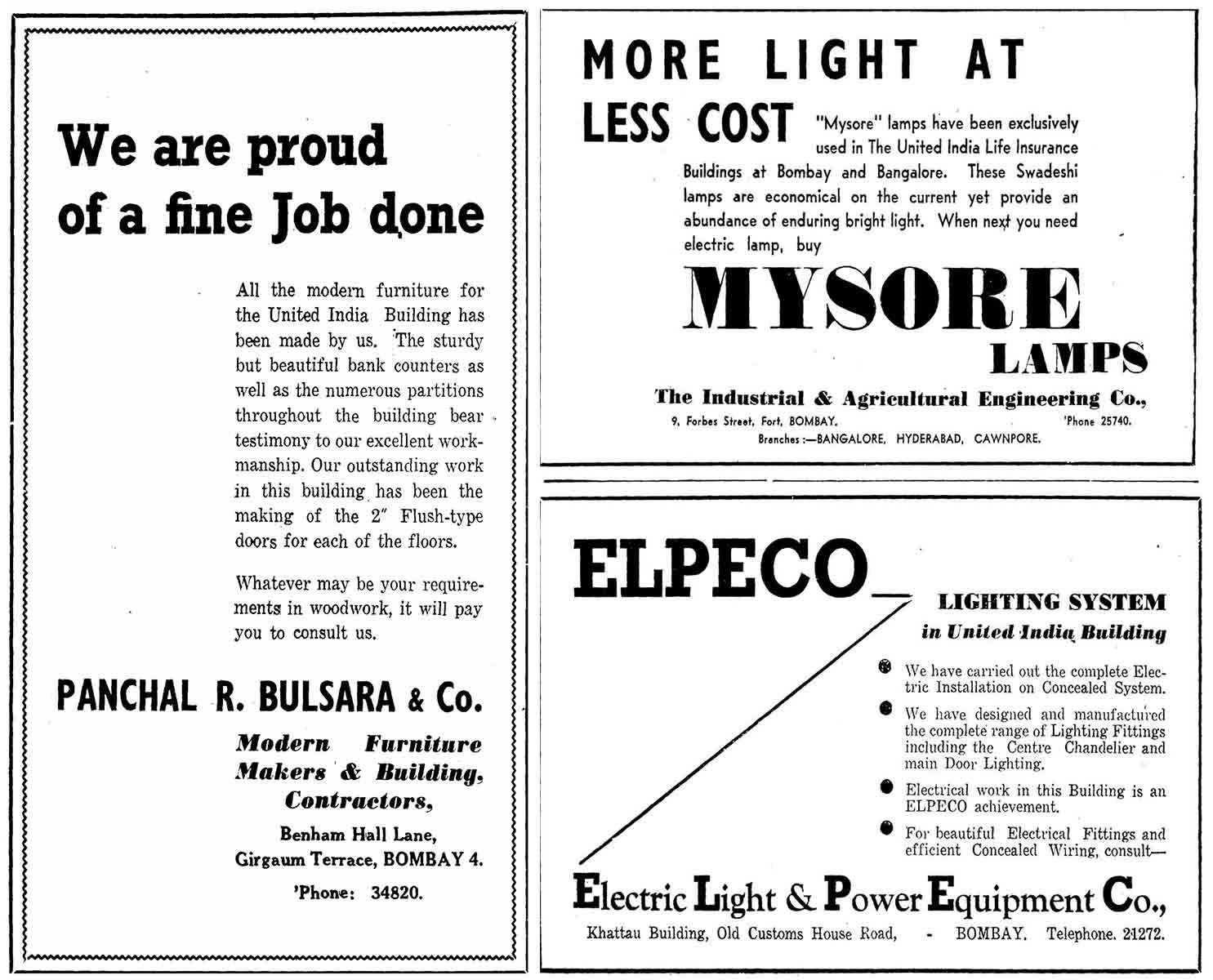

Beyond the messages delivered by their striking facades, the insurance offices functioned as de facto advertisements for the objects and materials they were comprised of. Every time a structure neared completion, the Times of India would release a comprehensive “building supplement” that documented the suppliers of each element of the new office, from its steel cabinets to its elevators to its marble tiles. The result was an architecture that exhibited the new style and its implied modernity not only in its frontage, but in its furniture, flooring, lights, railings—down to every last detail. The partnership between designers, manufacturers, and insurance companies suggests that, more than just a convenient choice, Art Deco was also an opportunity to promote a network of local artists and material suppliers. This tactic is suggested by the Industrial & Prudential Insurance building, now known as Industrial Assurance building, in which ground-floor retail space was let out to Kamdar Limited, a local design firm responsible for most of the decoration within the office.[14] Many native suppliers explicitly referenced the insurance buildings in their advertising. An ad for the Industrial & Agricultural Engineering Co. of Bombay, for instance, proudly stated: “‘Mysore’ lamps have been exclusively used in The United India Life Insurance Buildings at Bombay (now known as United India Building) and Bangalore. These Swadeshi lamps are economical on the current yet provide an abundance of enduring bright light.”[15]

Besides publicising the work of Indian decorators, the insurance buildings became advertisements for their own companies as well. The architects used distinctive Deco typefaces to fix the names of insurance firms on their facades: “Western India House” and “Bombay Mutual Building” were spelled out in recognizable streamlined fonts on their façades, while United India Insurance had its name embedded into the central tower of its office in five-foot-tall majuscule letters. With its predisposition to advertising and its integrated ornament, Art Deco architecture thus became a convenient mode of expression for Indian insurance firms looking to both establish their own brands and promote those of native entrepreneurs.

The Image of Insurance Deco

The Art Deco of Bombay’s insurance offices was also distinct in the way architects modified the buildings to suit regional conditions—in this case, the harsh climate. In its general form, Art Deco architecture did not hold up to the rain and sun of the tropics, with plaster surfaces requiring continual upkeep and creating what Claude Batley, a prominent architect, President of the IIA, and professor at the JJ School of Architecture, called an “unbearable glare” in the summer months. [16] Nevertheless, the inherently protean nature of Art Deco made it adjustable to new geographic contexts, allowing architects to transform the global style into a more “national” one.

The architects of the insurance offices often addressed issues of climate through choices in fenestration. The Western India House was designed around a void in the building’s centre that allowed for what one Times of India reporter considered “the sunniest and airiest offices to be seen in Bombay.”[17] The Warden House, built in 1941 as the office of the Warden Insurance Company, programmed the upper room of its circular tower for directors’ meetings, where optimal exposure to sunlight inferred an enhanced prestige. Although the New India Assurance Building included an artificial cooling system, its design involved “east-west façade windows [that] were generously shaded against the tropical sun; these could be opened to catch the sea breeze.”[18]

The Lakshmi Building now known as Lakshmi Insurance Building incorporated a more traditional feature that, in true Art Deco fashion, was used in a both functional and decorative manner: chhajas that provided protection from sun and rain.[19] Its simultaneous aesthetic and practical value was praised by Batley for its ability to “woo every breath of cool breeze” and ventilate a building naturally, thereby replacing artificial air-conditioning. The latter tactic, he warned. represented the seductive ease of Western technology and was “exactly the danger that India faces today, the losing of her individuality.”[20] The architects of the Art Deco insurance offices seemed to heed his call, participating in an international design movement while also keeping vernacular practices alive.

A distinguishing feature of the interwar insurance buildings could be found in their stone cladding. The local architects seemed to prefer a heavy exterior appearance, despite the fact that they were actually using new construction techniques involving steel and reinforced concrete. While the visibility of modern building materials would have advertised an image of technological advancement, it is interesting that the architects chose to forego its symbolic potential, even going so far as to disguise it.[21] The unconventional stone appearance of the Art Deco offices thus held symbolic significance, drawing parallels with both the surrounding imperial structures and a more distant indigenous architecture. By using heavy ashlar, the architects primarily referenced the older banks around them,

adopting their time-tested material representations of reliability. Following the First World War, the banking industry had revitalized an undesirable tract of land in Fort; by echoing their stone-clad appearance, the insurance buildings were perhaps also appropriating their prestigious urban image.[22] Beyond colonial mimicry, the stonework of the insurance buildings also echoed the materiality of both Mughal and Hindu architecture, two indigenous styles that used stone and, like Art Deco, dealt in shallow exterior sculpture.

While their choice of materials may have been less bold than those of the flamboyant Regal and Eros cinemas, the exterior surfaces of the insurance offices made up for this moderation, accommodating carved decorations that interlocked several cultural aesthetics. The architects and insurance businessmen were able to advance their swadeshi goals by hiring local sculptors to carve elaborate reliefs, thus sustaining native artisanal practices.[23] The modern, foreign style paradoxically kept Indian traditions alive and also made evident the formal similarities between Art Deco and indigenous architecture. It was Art Deco’s nomadic character—and its consequent propensity to meld every visual tradition it encountered along its way—that allowed local architects to incorporate Indian symbols into the architecture without disturbing the overall integrity of the style.

Of all the Art Deco architecture in the city, the insurance offices are most striking in their substantial incorporation of traditional imagery, especially on their façades. It is curious that the buildings bore visuals that were quite distant from their urban function—financial services—and location in the heart of Bombay. The Lakshmi Building is perhaps the most extreme example: crowned by an 18-foot statue of the eponymous goddess, which was executed by Goan sculptor R.P. Kamat, its ground-level entrance is flanked by large elephants carved into the Malad stone. The symbolism continues in lotus patterns on wrought iron gates and the elephant motif is repeated in red sandstone panels along the façade. The insurance owners’ dedication to illustrating their firm’s namesake indicates a desire to embody the affluence and luck of the mythology they reference, by literally inscribing it into the front of the institution.

While the Lakshmi Building adopted a spiritual iconography, several insurance buildings displayed more secular images of both rural and urban India. The entrance of the New India Assurance building, for instance, is flanked by larger-than-life bas-reliefs by sculptor N.G. Pansare, in which “industrial labour with looms and wheels, farmers with bales and winnows, and common village professions and chores appear in a simplified gigantism in an attempt to connect the two Indias that were poised to diverge into their respective destinies.” A similar approach was taken for the People’s Insurance Co. Ltd office (now known as Onlookers Building) —its façade displays stacked bas-reliefs by local sculptor Shiavax Dhanjibhoy Chavda, portraying scenes of rural Indian life and a militant, sari-clad figure dominating the topmost panel.[24] She is flanked by two Swaraj flags, which Mahatma Gandhi had adopted in 1921 as an emblem of his civil struggle against the British Raj. The design, which would eventually evolve into India’s current flag, includes a chakra at its center, a spinning wheel used to make the homespun cloth that became a metonym of swadeshi ideology.

Dressed in traditional attire, the figures on the insurance buildings glorify pastoral life in a manner seemingly counterintuitive—and perhaps even self-orientalising—for insurance firms that had become embedded in the technology-driven urban milieu. Yet in doing so, they may have been hoping to adopt the ideals of honesty and trust represented by the humble Indian hinterlands to augment their public personas and to translate their financial services to romantic, simple terms. Above the entrance of the Western India House, for instance, one panel depicts a rural moneylender handing a sack of coins to a farmer with a pickaxe, a rudimentary illustration of a financial service. Furthermore, the strategic placement of these panels around the buildings’ entrances would have reminded customers of their shared cultural inheritance, rooted in the distant but persisting realities of Indian life.[25] Ultimately, in all cases, the amplified visibility and expressive intricacy of Art Deco made it a convenient medium of announcing the insurance firms’ financial principles and larger loyalties.

In the case of the insurance architecture, the designers’ weaving of distinct aesthetics implies the level of agency involved in the process. This falls in line with Jarava Lal Mehta’s understanding of cultural negotiation in the colonial context, in which the act of self-discovery for a colonized population necessitates a process of Europeanization and removal from tradition in order to ultimately return to cultural roots. “Here as elsewhere,” he says, “the way to do what is closest to us is the longest way back.”[26]

A Legacy Lost

Today, the city contains one of the largest collections of Art Deco structures in the world, but the style assumes a quiet presence as one of many layers in an urban palimpsest. This presence not only introduced a new aesthetic texture to the city, but also allowed architects and entrepreneurs to formulate a new cultural identity outside the control of the colonizers. In the case of the insurance buildings, this identity was arguably nationalistic, articulated in the strategies they used to simultaneously appropriate the supremacy of imperial institutions, tether their businesses to a distinctly Indian heritage, and evoke India’s evolution into a modern and autonomous nation state.

The paradox of a native divergence from Western modernity via a modern style is especially interesting considering Art Deco’s

relatively belated adoption in India. It is still characteristic of colonies to learn of and apply cultural trends after they have already fizzled out in their original birthplaces. Indeed, by the time the insurance buildings were fervently being erected in the years between the wars, Art Deco and its overt embellishment had waned in Europe and the United States. The Western world was by-then enamoured by the rigid, minimal International Style. While the Indian elite may have happily used Art Deco to assert their social standings or political stance, one could argue that they did so while trapped in an everlasting state of cultural aspiration. The style’s late espousal nevertheless came at a convenient time—its expressly communicative nature resulted in blatant symbols of a changing socio-political order. The defiant female figure atop the Western India House attests to this expressive capacity, but would not have been possible were India using the most current architectural trend of the 1930s.

In later decades, however, the offices of Bombay would go the way of austere modernism. Not far south of the insurance buildings in Fort, a new business district called Nariman Point emerged on reclaimed land. It quickly thickened with glass skyscrapers that demonstrated a new preference for the repetitive functional elements of the modern movement over the idiosyncratic decoration of Art Deco. A familiar narrative of corporate copying emerged, and this might be the true legacy of Bombay’s Art Deco insurance buildings. While claims to the sensitivities and intentions behind later commercial architecture cannot be made here, it is clear that in Bombay, as in many megacities in the developing world, the native population found it difficult to escape the legitimizing allure of architectural trends that were born in the West and nurtured by the material requisites of modern capitalism. With increasingly connected commercial and technological networks, commercial architecture has become more uniform than ever— the crystal towers in the northern Bandra Kurla Complex, the latest nexus of the Bombay’s business, are indistinguishable from those of Hong Kong or Jakarta. Considering this present reality, the Indian insurance firms’ translations of the Art Deco style during the late 1930s might have been one of the last concerted efforts to regionalise a global design movement, to confidently insert a national sense of self into a larger architectural conversation rather than succumb to it altogether. While these structures are still in use today, that they endure in conditions of terminal neglect is a patent and impending tragedy for the cultural legacy of Bombay.

Maya Sorabjee for Art Deco Mumbai

Maya is originally from Bombay and is currently an M. Arch I candidate at the Yale School of Architecture. She received her undergraduate degree from Brown University in Architectural History and Urban Studies. Her research and design interests include social housing, postcolonial cities, vernacular architecture, and adaptive reuse.