‘Modern Heritage’ refers to built heritage of the Modern Era recognised for its historic and cultural value, often undervalued by the general public.[1]

To explore the notion of Modern Heritage, this article chronicles the era of Modern Age, highlights the tangible cultural legacy that followed, and seeks to develop an understanding of its significance. It also questions the relevance of time as the only pertinent factor in the process of identifying heritage, especially significant architecture such as Art Deco buildings from the early 20th century in India.

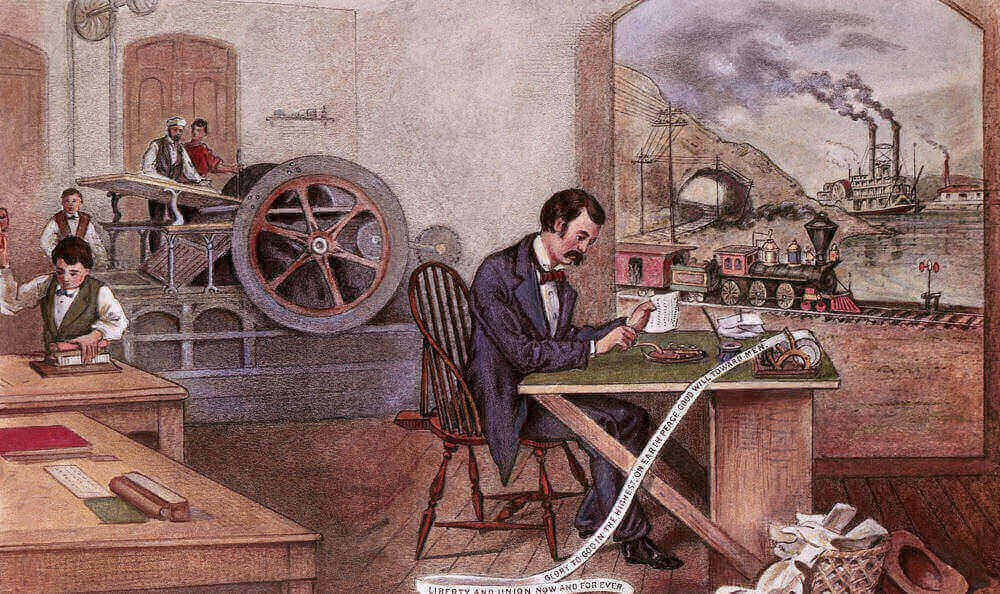

The era of Modern Age globally began at the end of 19th Century with the advent of Industrialisation. This era with its pool of new ideas, technological advancements and material innovation offered many opportunities that led people from agrarian and rural settlements to industrial and urban centers. These opportunities also aimed to break away from material constraints in expressing historical styles and moved towards an era that aspired innovative ideas that resulted in functional, efficient and minimalistic designs. Using new and improved materials such as cast iron, glass, steel and concrete in construction led to creating sleek and new age buildings with efficient spaces that promoted a new way of living and aspired modernity.

Progress in technology, obsession with speed and desire to move forward led to the innovation of locomotives, airplanes, automobile and ocean liners. These means of transportation not only eased local commute within world cities, but also made it easier for people to travel to faraway lands for business and pleasure. Simultaneously, new patterns of lifestyles such as family outings to cinema theaters, youth gathering in social clubs and women socialising in mixed gathering changed the ways people perceived their present and what they aspired for their future.[2] The growth of cinema in this period and later television further facilitated faster transmission of information and ideas all around the world.

Global events such as the World War I (Great War), World War II and the Great Depression made the survivors evaluate their lifestyle choices and ways communal resources were utilised henceforth. People choose to move away from a lifestyle of ornamentation and opulence to one that was more utilitarian and functional. These choices reflected in the ways buildings were designed and the kind of materials that were used for construction in early 20th century. They gave preference to structural and geometrically driven design aesthetics that could be constructed inexpensively in a shorter span of time.

These global events also had a significant impact on the mindsets of well-travelled and educated Indians. Simultaneously, homegrown events such as the Jallianwala Baug massacre, Non-cooperation movement (1920-22), Satyagraha movement and a growing desire for complete independence (1929) and, self-governance in India inspired a sense of nationalism in their hearts.[3][4][5] The desire for freedom complemented the aspirations that modernism offered – a departure from the norm which at that point was all things colonial. Buildings constructed in India during this period showcased a sense of patriotism with a strong international outlook. Today, many of them form a significant part of the skyline in different cities of India, especially Bombay.

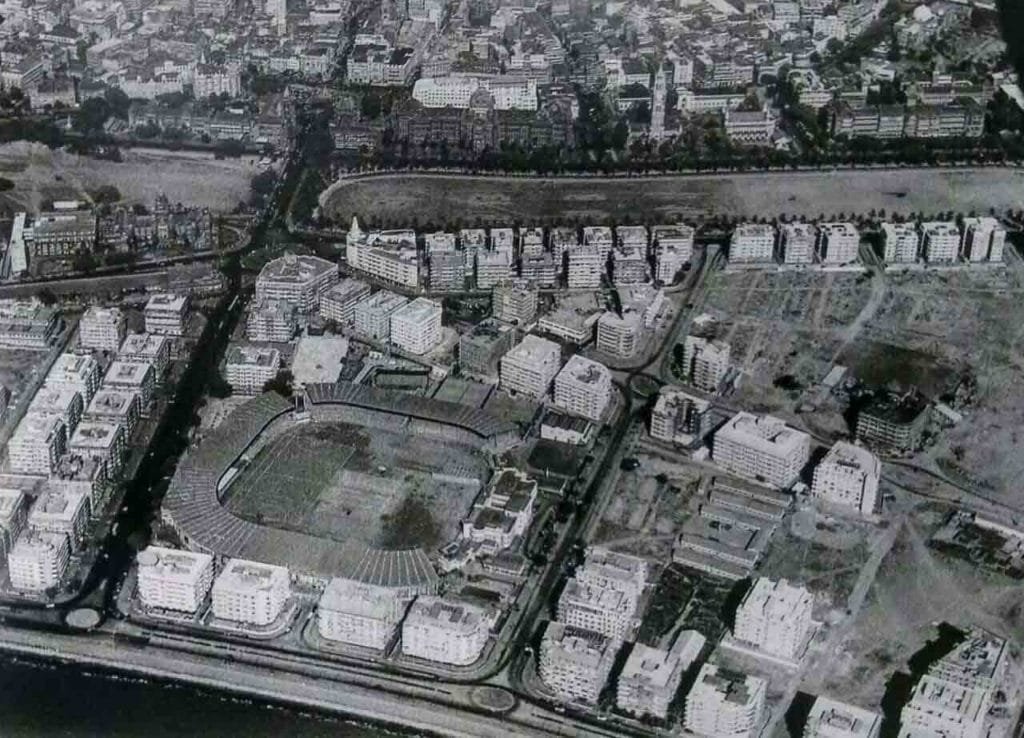

During the inter-war period in the early 20th century, Bombay was at the heart of architectural thinking in India.[6] Indian Institute of Architects was headquartered here along with many well established and new architectural firms, led by Britishers and Indians respectively who were actively engaged in the building practice. Newly trained architects (especially Indians) graduating from schools abroad and from Sir J. J. School of Architecture in Bombay moved away from the Edwardian and Victorian styles of architecture and embraced the modern ways to design for the growing population in the urban center of the country.[7] Art Deco, International Modernism and the Modern Indian Architecture movement were the design philosophies that were considered modern by the pioneers of architectural design at this time.[8]

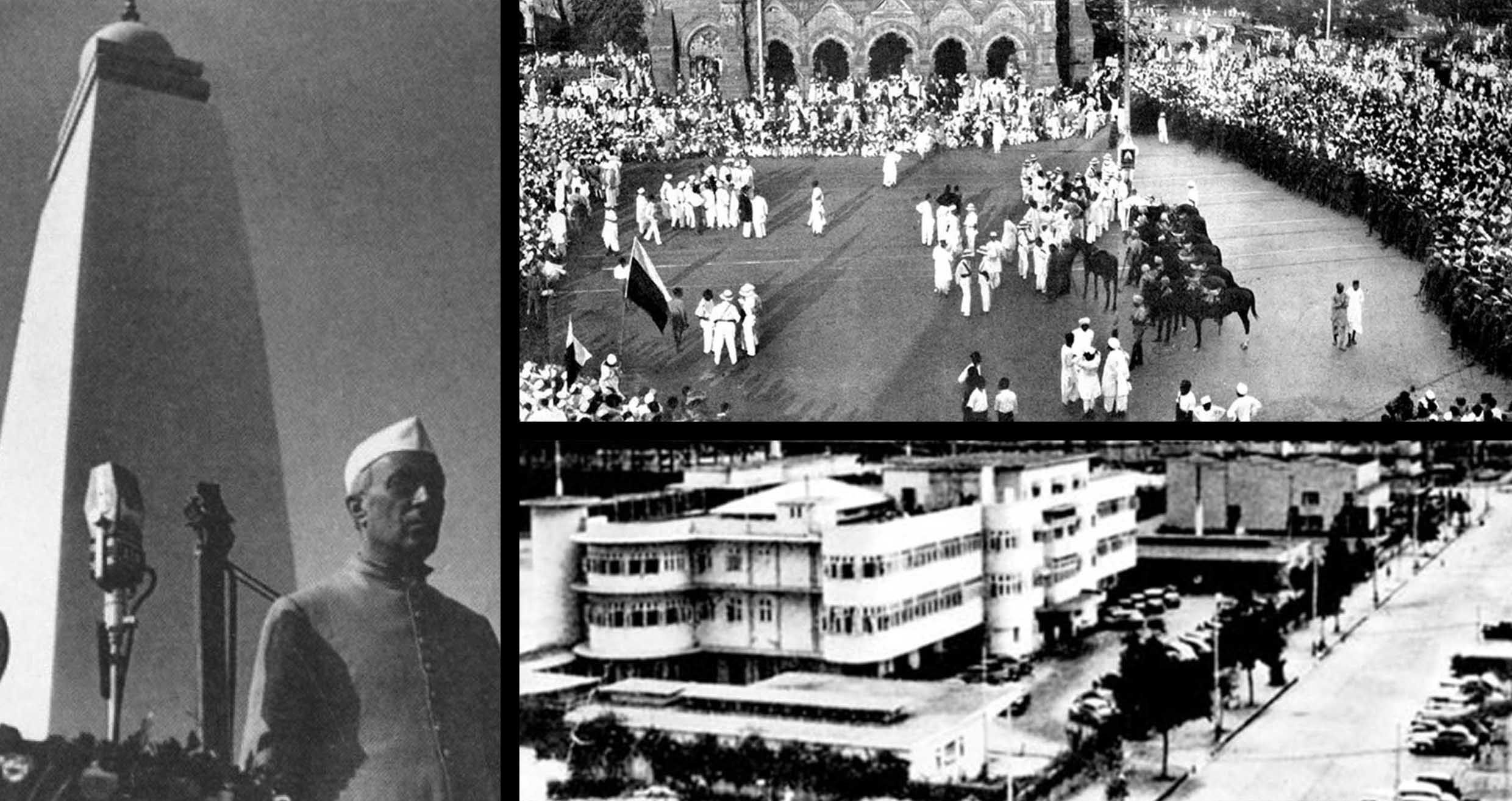

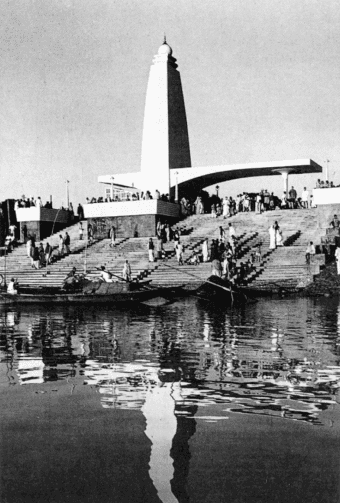

Art Deco entered the Indian subcontinent from Bombay, through the desires of Indian princely statesmen, merchants and entrepreneurs to express their love for the contemporary ways of modern living. It signaled the arrival of appreciation for modern aesthetics to India. Ornamentation, a significant part of expression in Indian architecture continued to be an integral part of the design language of Art Deco; only evolved into a minimal and geometrically driven design feature.[9] The new emerging architectural spaces in Bombay and other Indian cities such as cinema theaters, social clubs, schools, hospitals and apartments were then being built in this modern style. As the style gained popularity, an amalgamation of Indian influences were observed in the design features and motifs (known as Bombay Deco or Indo Deco) as compared to the European influences that were initially prevalent. The style was also seen to simultaneously have a more direct influence on peoples’ lifestyle through design fields such as industrial design, graphic design, fashion and mass-media. Although the design sensibilities of Art Deco in the West thrived on industrial means of production, in India the building style continued to use manual labour for construction.[10] This gave buildings a hand-made quality unlike its western counterparts while creating a pool of highly skilled workforce essentially easing the architectural transition in late 1940s.[11] Later, Modernism was promoted under the leadership of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru as he believed it was an appropriate vehicle to represent India’s agendas as an emerging nation.[12]

Jawaharlal Nehru believed that architecture played a vital role in building a cultural vision of a new, democratic and egalitarian society. The radical modern movement in Europe with its socialist roots was a model of inspiration for him.[13] Major cities across the country at that time were being developed by the funds given by state and/or by philanthropically inclined citizens. State sponsored Chandigarh and Delhi was being built by modernist European and British architects, and Indian architects with American education respectively. Philanthropic citizens primarily funded the development of Ahmedabad and Bombay by Indian and International architects.[14] Nehru and other leaders of modern India like Maulana Abul Kalam Azad personally engaged with young Indian designers to develop a design vocabulary which was rooted in Indian traditions but pointed to a new future.[15] This continued to evolve and led to the development of modern Indian architecture which in many ways defines the image of the Modern Independent India.

“Architecture has been called the art of building beautifully, a fixation of man’s thinking, and record of his activity… Keep in mind that last phrase. It is important.” -Ernst Johnson, colleague of Eero Saarinen

A series of historically significant events of national and local importance led to the formation of a Modern Independent India in 1947. The buildings built especially since early 1930’s bore witness to a very important period in our nation’s history. They captured the aspirations of colonised India ready to be independent and self-reliant. They later became precedence for newer cultural expressions that formed the identity of the emerging Modern India, especially in its urban centers.

We have conditioned ourselves to appreciate the urban fabric through our everyday experiences and shared memories. [16] Our collective experience at the present time is evolving at a much faster rate than they did a few centuries ago. There has been a drastic increase in population with an urgent need for infrastructural development. Technological advancement and innovation in the field of transportation and communication have brought the world closer than ever. This pace of change is leading to the creation of homogeneous towns and cities nationwide. In the midst of these transformations, it is our heritage that act as cultural anchors and affirm the identity of the community.

Heritage is defined as valued objects and/or practices such as historic buildings and cultural traditions that have been passed down from one generation to another.[17] The objects are deemed important due to the value(s) they gain over time. These values can be due to age of the object or practice, association with importance figure or period and its significance as a work of art or expression, among others.

Abundance of ancient built heritage in India has skewed the way we assign different values to buildings and how we prioritise these values. At present, the buildings mainly need to have survived in the consciousness of its community for a long period to gain recognition/value and to be considered heritage status.

“Some things are worth keeping even if they do not have a patina acquired with age.” – Kamu Iyer, 4 from the 50’s: Emerging Modern Architecture in Bombay

Quality of life depends on the positive sense of identity, belonging and place.[18] These thoughts evolve through time; hence it is very important for one to understand where the shared ideas are rooted in past, so they can develop a better understanding of the present and ideate to move towards a better future.

All human development occurs in the cultural context and is intrinsically linked to community development.[19] Representation of built histories from different time periods in our urban and rural environments is what makes these environments architecturally rich and diverse. These spaces stand the test of time and witness many historical events (national, local and/or individual), acting as a memory bank.

Most of buildings built in the 20th century like Art Deco buildings and precincts are valuable resources that were built for the emerging Indian, who aspired to be modern and desired healthier living spaces. They were also designed with the intention that evoke a sense of ownership while transcending time. Unfortunately, majority of these buildings are not considered old enough (in the conventional sense) to be called heritage nor are they active urban memories of younger generations. Lack of their appreciation, recognition and legal protection as our heritage has led to their defacement and even demolition, triggering the loss of these physical markers from a historically significant chapter of modern India.

To ensure that we don’t lose many more such buildings, it is very important that we improve our communal understanding about them through capacity building and community outreach programs. These buildings need to be identified, documented, protected and conserved for they define a historically significant period from our collective history and to a large extent define our contemporary society.

We need to realise the importance of safeguarding and protecting these outlier buildings to ensure that they are a part of the urban memory. It is imperative we act now else many of these milestones would disappear.

Nityaa Lakshmi Iyer for Art Deco Mumbai.

Nityaa is a conservation architect and researcher with a Master’s in Historic Preservation from the University of Pennsylvania. She was also a Getty Graduate Internship fellow where she worked on design proposals for architectural intervention in archaeological sites and a Sardegna Research fellow where she worked on the historic structures report (Phase I & II) for a 20th century heritage building.