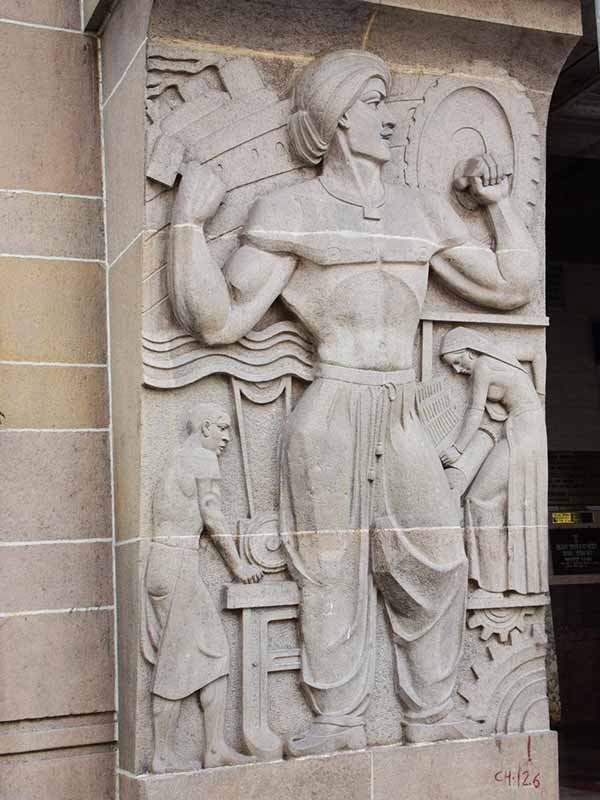

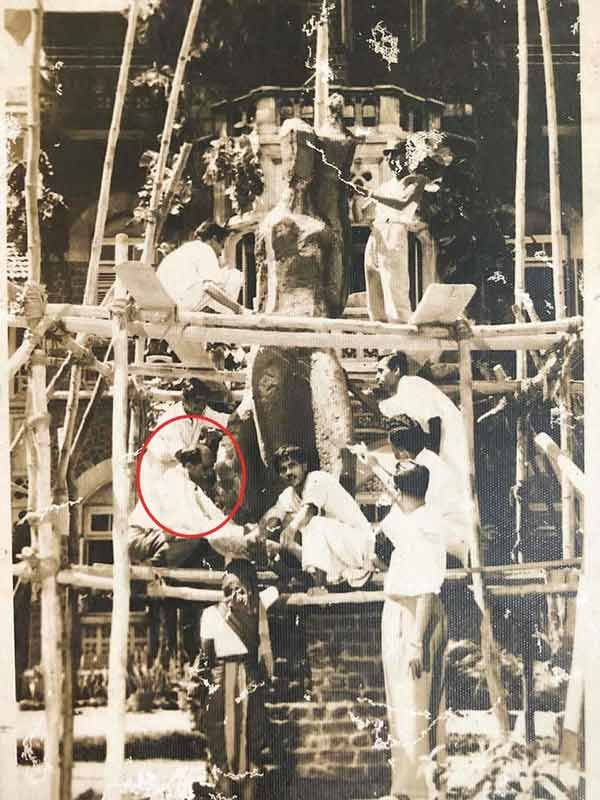

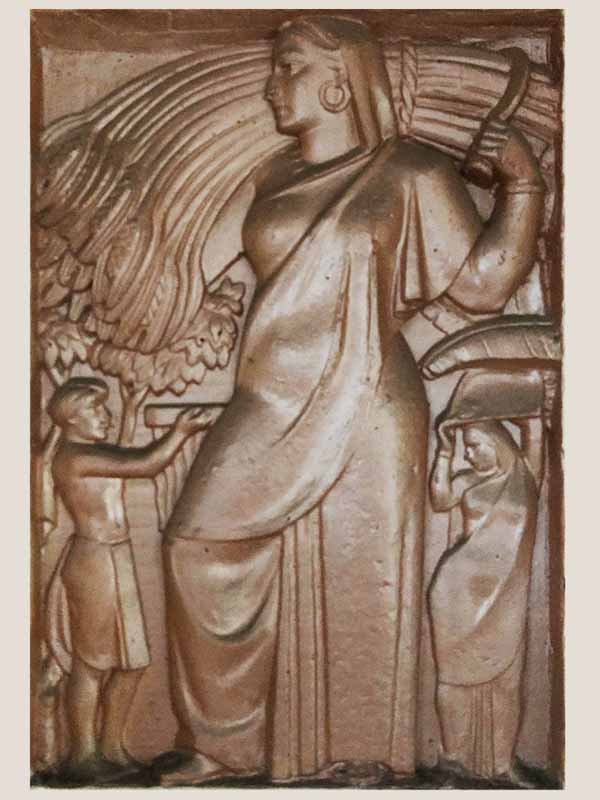

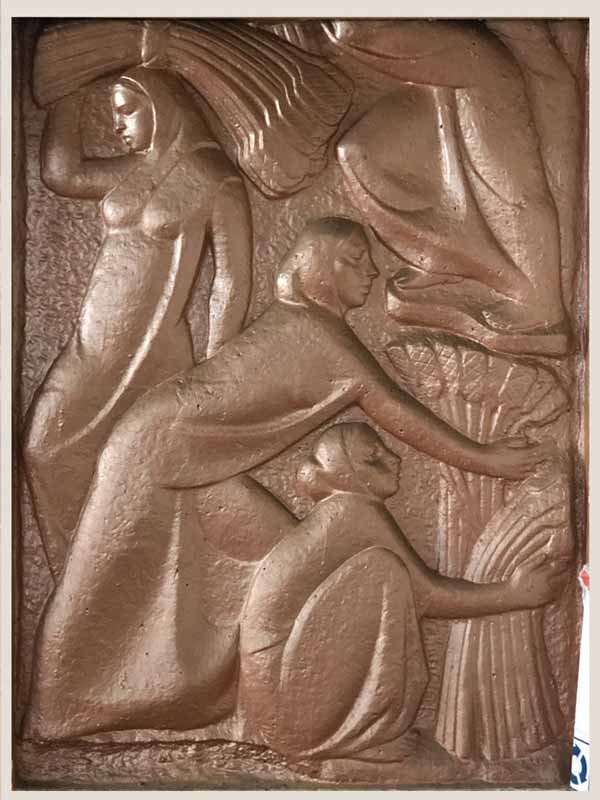

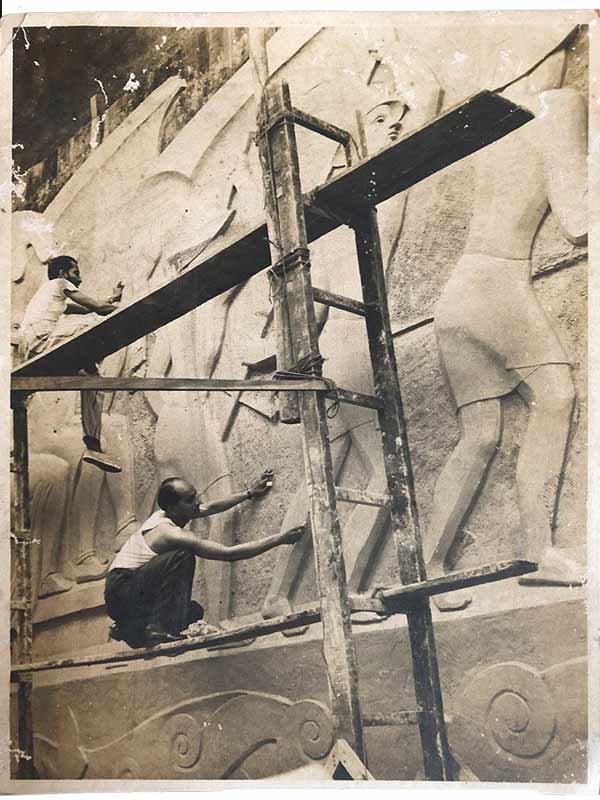

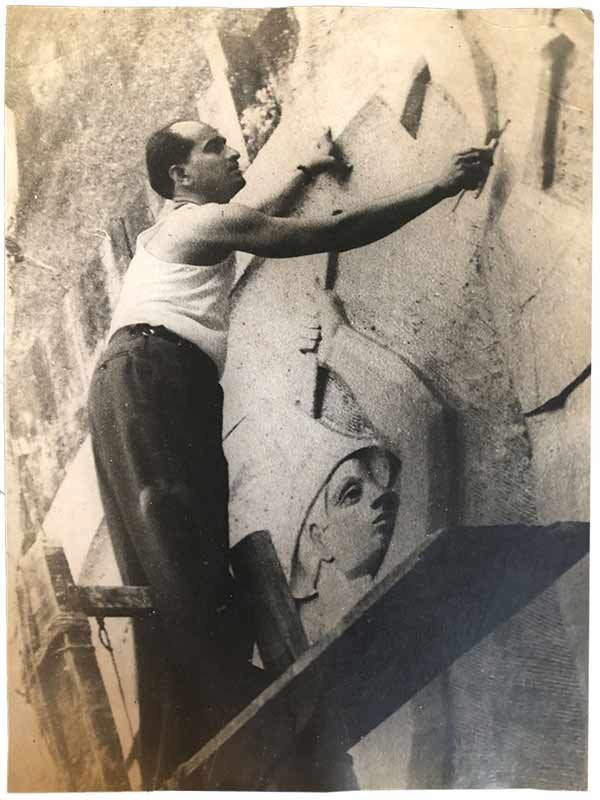

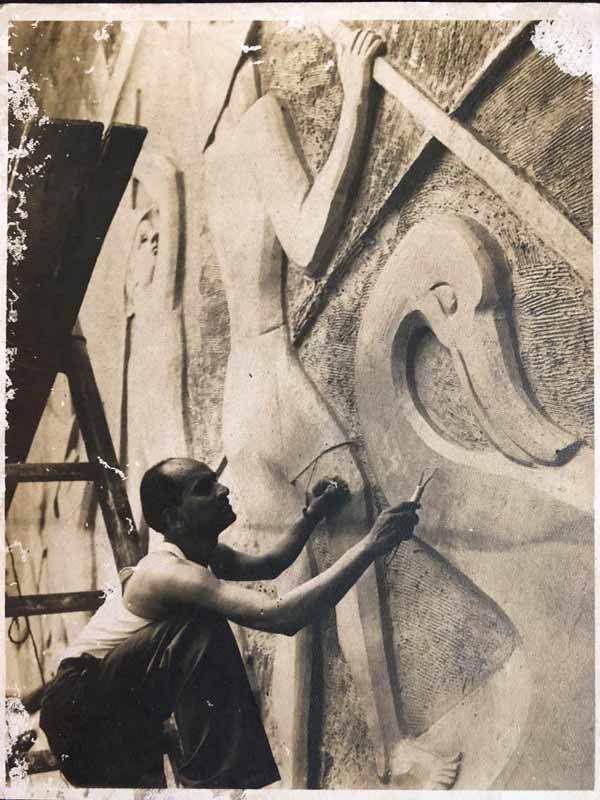

Amidst the busy business lane of Mahatma Gandhi road in Fort, Mumbai, an Art Deco building with imposing bas reliefs catches the eye of a hurrying office worker or a flaneur on a casual stroll. The facade of the building is flanked by two massive figures in relief work showcasing the working class of the Indian subcontinent in the traditional clothing of saris and dhotis. The New India Assurance building constructed between 1935-37 by the architectural firm Master, Sathe and Bhuta, is a visual delight with iconic imagery on the facade, sculpted by eminent Indian sculptor Narayan Ganesh Pansare who worked together with the firm to create them.

The New India Assurance building, is one of the outstanding examples of the Indo-Deco[1] architecture in Bombay (now Mumbai). The Art Deco building has vertical ribbing and Egyptian style carvings on either side of the entrance. Standing almost six floors high, the gigantic carvings make the building appear monumental. Made of reinforced concrete cement, it had an early air cooling system installed along with central air shafts, horizontal projections and windows on the East-West facade to protect from the sun and let in the sea breeze;[2] it was constructed in a manner similar to modified classicism giving it a serious and solemn look as opposed to the grander edifices of Mumbai’s Art Deco cinemas.[3]

“In a time of political upheaval as Indian nationalists agitated increasingly for independence, the Art Deco was too radical an art form to be acceptable to imperialists and too foreign to be acceptable to swaraja idealists. Nevertheless, to a number of wealthy clients and architects, particularly in Mumbai, Art Deco was the expression of modernism.”

– Jon T. Lang, A Concise History of Modern Architecture in India.

The New India Assurance Co Ltd. is one of the many Indian insurance firms that proliferated and set up in modern India, especially in the Fort area, the commercial hub of Bombay[4]. It was founded by Sir Dorabji Tata in 1919, at a time when Indian businessmen were setting up their own insurance firms rather than just being partners in foreign firms; Swadeshi enterprises (those made in India and owned by Indian businesses) were being advocated and encouraged during this period.[5] It is then fitting perhaps, that the reliefs sculpted by Pansare paid tribute to the Indian working class; two of the monolithic figures consist of a man and a woman depicting the two major economic pillars of India at the time. A woman carrying bales of produce, her sari folds expertly sculpted in Malad stone while people in the background carry out various farming activities represents the agrarian sector, while a man in a turban and dhoti holds mechanical parts like a cog and a wheel, indicating the industrial sector. Other symbols carved into the facade like a lamp, a bird, a pot of water, and a basket of fresh produce seem to symbolize abundance, freedom, knowledge and hope for a better future.[6]

N. G. Pansare was active, both during the period of modern Indian art (1750s-1947) and the beginning of contemporary Indian art (post independence). Described as a “non-conformist,” who brought a frontal and pictorial quality to his relief works,[7] he enmeshed art and modern architecture creating some of the seminal work we see today. He expertly designed the New India Assurance gigantic reliefs to combine with the architectural style of the building in a simplistic yet effective way; indeed, monumental sculptures seamlessly integrated with his own style were his speciality and made his works unique and stand out amongst others. His style ranged from the European naturalistic style to the Egyptian style motifs seen on the New India Assurance building, while his themes and imagery progressed from European to increasingly Indian ones; he made use of several materials to create his works like wood, bronze, terracotta, marble and stone.

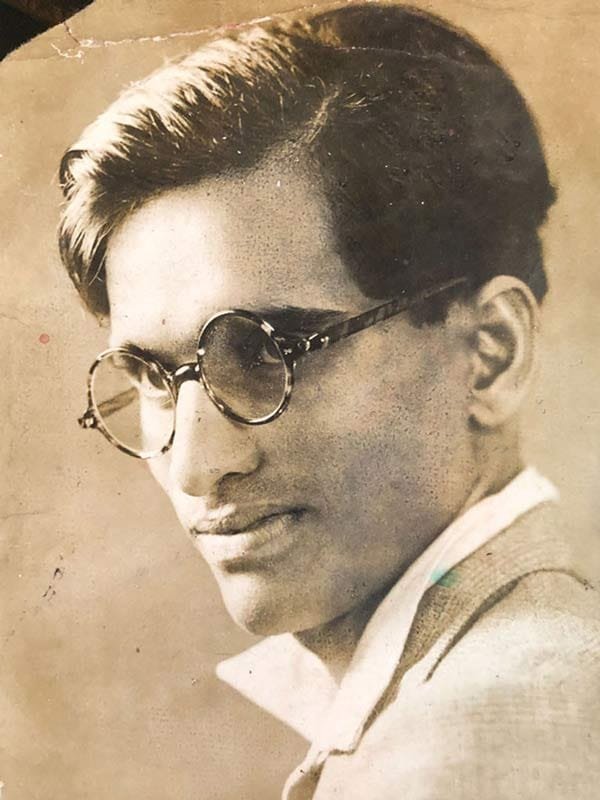

Narayan Ganesh Pansare (N. G. Pansare) was born in 1910 in the coastal town of Uran, British India.[8] Like many modern Indian artists of his time, he attended Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay to formally train in sculpture making. This School founded in 1857, was one of the most prestigious institutes of fine art education in colonial India and is named after the first Baronet, Sir Jamshedji Jeejeebhoy, whose donation made its establishment possible.

The School’s Sculpture department was crucial in aiding the development of modern Indian art[9] and sculpture. In her article, Dr. Ami Kantawala states that significant transformation occurred in the School after the arrival of John Lockwood Kipling and John Griffiths in 1865 – it was due to their efforts that the use of relief sculpture in the decoration of public buildings gained popularity.[10] In the 1930s, professors like Shri G. K. Goregaonkar and Mr Fernandez popularised Indian sculptural reliefs, while in 1936 the idea of social sculpture by Charles Gerard made Monumental Sculpture (that is, sculptures that are either large in scale or those that are present on architectural relief works) a significant field of study.[11] The sculpture department evolved from architectural sculpture to decorative carving and portraiture to monumental sculptures; Pansare dabbled in all of these fields of sculpting, which serves as a testament to his versatility and the impact of his education at J.J. on his career. Pansare’s contemporary sculptors who attended J.J. School of Art included the likes of Balaji Talim, Sadanand Bakre, V. V. Manjarekar, Shri Arte, Vinayakrao Karmarkar, Himmat Shah, Shri Jog, B. Vitthal and many more.[12]

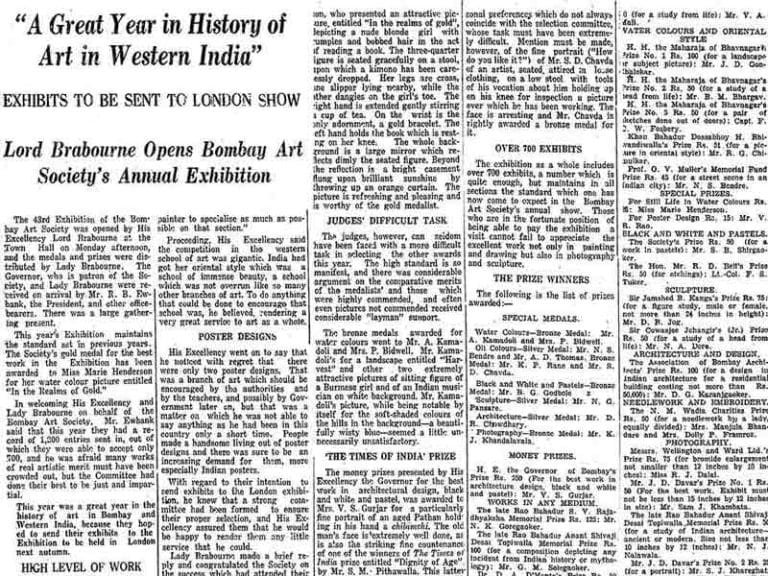

Pansare excelled in academics at the School and won several awards even before he graduated. Awarded the First Prize in his IV year (Advanced) exam, he also bagged the Earl of Mayo Medal for the ‘Best Student of the Year.’ His promising talent was recognized at a young age by art societies and British authorities alike; societies like the Bombay Art Society (est. 1888) granted him the ‘Silver Medal’ and a cash prize, and the British authorities granted him ‘H.E. the Governor’s Special Prize.’ He was also the recipient of the Ganpat Kedari scholarship and the Rao of Kutch scholarship, and granted the G.D. Art (Sculp.) Diploma where he stood second in order of Merit.[13]

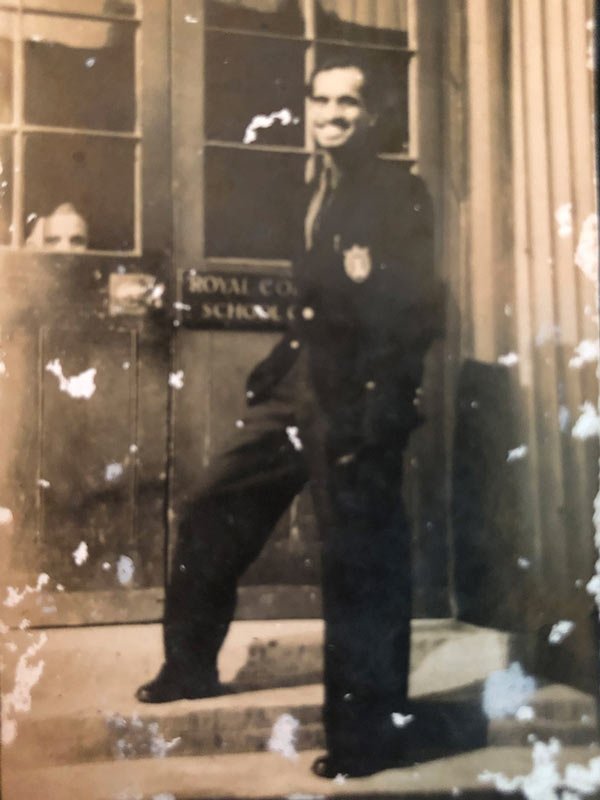

After the end of his five year term at J.J. School of Art, in 1938, with such remarkable accomplishments under his belt at age 28, he boarded a ship for London to attend the Royal College of Art (R.C.A.) a public university established in 1837 in London, England. At the R.C.A., Pansare studied wood carving, stone carving, bronze casting, life drawings, architectural and monumental sculptures, pottery and foundry work, and animal sculptures and drawings under professors like John Skeaping, Alfred Trumer and Richard Garb.[14] Alongside his university studies, he also attended evening classes in London. He graduated from university in 1940 with a Degree of Associateship (A.R.C.A) and went back to India in the same year.[15]

He returned to India during an interesting era. Against the backdrop of World War II and ideas of revolution, new schools of art emerged in the 1940s that rejected the earlier nationalistic or ‘revivalist’ art.[16] Instead, they placed an emphasis on ‘international modernism’ (often taking inspiration from Western art styles such as cubism, expressionism etc) and an individualistic style.[17] At J.J. as well, professor Charles Gerard inspired students to look beyond Western institutional art and incorporate Indian art forms.[18] Bombay witnessed the formation of the Progressive Artists Group (PAG) by artists like M. F. Hussain, K. H. Ara, F. N. Souza, S. H. Raza, H. G. Gade and Sadanand Bakre (the only sculptor in the group). Although not a part of the PAG, Pansare sought to break away from the status quo of commissioned works and decorative pieces in his own way by taking on numerous architectural relief works and infusing them with his own style.

Artist and critic Jaya Appasamy in her book An introduction to modern Indian sculpture, asserted that to understand the development of the colonial art style and its adoption by Indian artists, a study of Bombay was crucial as it was the hub for the “greatest sculptural activity” from the 1900s-1940s.[19] She lists out reasons for this such as the easy assimilation of colonial art by the Bombay art societies and universities, and the explosion of Bombay’s commercial activity as a port town which had a wealthy clientele who liberally commissioned works of sculpture. There were also numerous competitions held by art societies in Bombay, which Pansare took part in and won quite a few, as seen in the Times of India articles below. They showcase his use of different materials for his decorative pieces, and the mention of ‘lively animal sculptures’ in wood and terracotta serve as a reminder of his lessons in animal sculptures at the Royal College of Art.

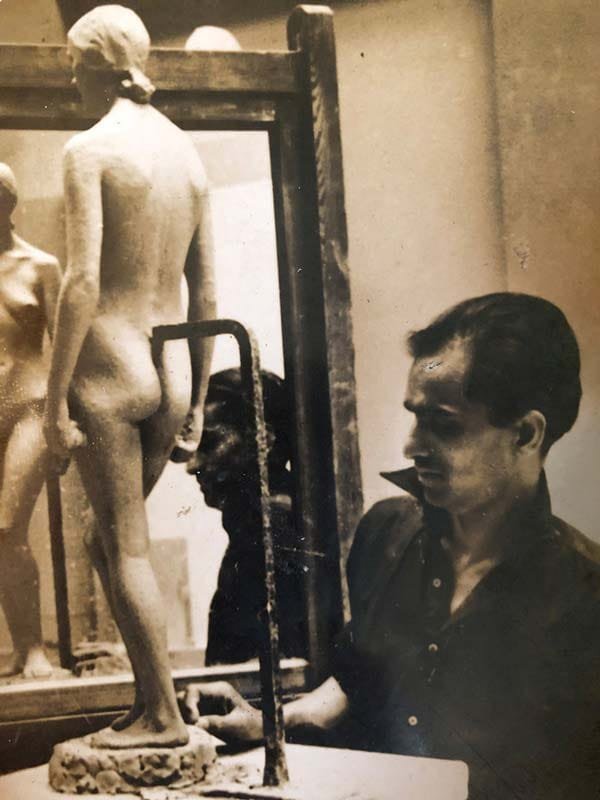

Appasamy states that monumental sculptures during this time were made primarily via two processes – carving in marble and bronze casting; the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj equestrian statue sculpted by Pansare, a famous landmark in Shivaji Park, Dadar, is an example of the latter. The two techniques used by sculptors at that time were arduous and required extensive planning which in turn resulted in numerous drawings, clay sketchings and plaster models. For marble statues, a block of marble was carved in exact measure to the plaster model while for the bronze statues, large scale models were prepared first then cast piece-by-piece and later assembled.[20] Kiran Pansare, son of N G Pansare, reminisces fondly about the construction of the Shivaji Maharaj statue (which he contributed in creating). “It is cast in bronze and assembled in the very backyard of this Bandra home where we are conversing today. The immense scale of the model meant that a crane was required to lift it”, says Pansare.

Kiran Pansare shared some of the instructions regarding the construction of the statue that the committee formed to oversee its construction and other advisors (consisting of personalities like filmmaker V. Shantaram) had issued to Pansare – “they wanted him (Shivaji) to be young, action-oriented,”[21] perhaps to showcase the vitality of the historical leader. The original design however, was quite different from what Pansare had in mind. Curiously, despite the committee’s instruction, they also requested the finished structure to have Shivaji Maharaj, not with an unsheathed sword in his hand, but extending his arm with his hand outstretched in an uncommon, almost benevolent gesture, as if asking people to “follow him.” The finished statue cast in bronze was 22 feet tall and 26 feet long. A viewing session of the finished statue was held in the backyard of his Bandra home and attended by prominent dignitaries of the time including Balasaheb Desai, the then Education and Home Minister of Maharashtra.

The Shivaji Maharaj statue was taken for erection in the night and installed on 6th November, 1966. “This (the statue) was made here, the mould and the casting, the foundry was made in the backside of our house at that time,” recounts Kiran Pansare. Around thirty pieces were made (the head, for example, was made separately) and then assembled together; N. G. Pansare had to acquire special permissions due to the large scale of the statue.[22]

The creation of the statue has a surprisingly grim backstory. According to Kiran Pansare, the statue’s sculpting resulted in losses for his father, due to a revision of estimates. Shanta Gokhale in her book Shivaji Park: Dadar 28: History, Places, People, describes the creative disagreements that N.G. Pansare had with the committee. After the plaster of Paris model of the statue was made, the committee had insisted on increasing the height, so as to not make it look ‘insignificant’ in the wide expanse of the Shivaji Park ground.[23] Pansare was displeased with the sculpture’s “follow me” gesture. He felt under pressure when the height of the statue was increased arbitrarily. Kiran Pansare also mentions that his father was a chainsmoker. The pressure of increased costs for the statue, a tight production schedule coupled with his habit of smoking could have contributed to his premature death just two years later, conjectures Kiran Pansare.

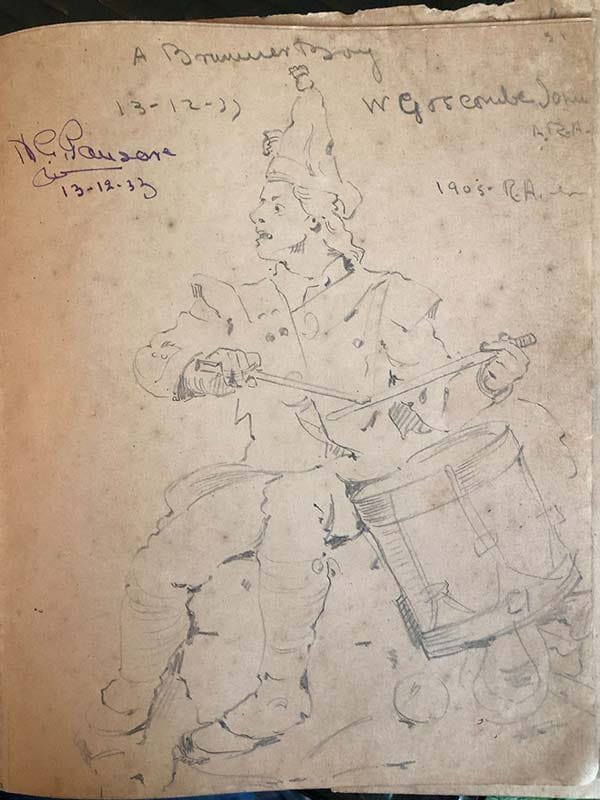

Since the processes of casting and marble carving during this time was laborious and the sculptural works were mostly commissioned and depended on the client’s approval and instructions (as evidenced by the Shivaji Park statue’s case), artistic freedom in sculpting was often restricted. Appasamy opines that the sculptor’s personal style was mostly seen in their sketchbooks and personal diaries, rather than their commissioned works.[24] Perusing N. G. Pansare’s diary/sketchbook that the Pansare family has preserved for many years, it was found that most of the sketches were made from 1933 onwards, a sketch labelled ‘A Drummer Boy’ (1933) being one of the earliest.

Moreover his sketches were mostly drawn in the European style and contained Western imagery which was commonly adopted by modern Indian artists who had received the company style/European style art education in India and abroad. Kiran Pansare supposes that his father’s statues could have been influenced by Western art forms by virtue of his training, though, ironically we see Indian influences dominating his work. Pansare’s expression – or perhaps, evolution – of Indian themes was seen prominently in his commissioned works, primarily the New India Assurance building, The Ashoka Hotel (New Delhi), the Laman Diya in Nandadeep Park, Bandra, and later the Shivaji Park statue.

Despite the obvious reference to the working class, the impact and the purpose of these themes in the New India Assurance building makes for interesting analysis. In the 1930s on the political front, parties which expounded communist and socialist ideologies were gaining traction in the spectrum of mainstream Indian politics. Shapoorji Pallonji’s book ‘Changing Skyline,’ mentions that the reliefs sculpted by Pansare on the Art Deco building had a certain ‘Soviet’ style[25], perhaps an expression of appreciation of the work undertaken by the largest working sector (the agrarian sector) of the subcontinent.

Although the purpose behind the carvings cannot be determined definitely, it highlighted the fact that there was a definite shift towards the representation of Indian imagery in the 1930s (seen by the traditional clothes, ornaments and symbols on the New India Assurance building) as opposed to the Western imagery seen in Pansare’s personal sketches. The Art Deco subset known as Indo-Deco added elements of Indianness (and in this case swadeshi), to the architectural style from the West.[26] The employment of Indian imagery commissioned by an Indian insurance company and designed by an Indian architectural firm was not unusual to this era of swadeshi ideals and the emergence of the Indo-Deco style.

Pansare also worked on other civic and private architectural structures including the Bombay Mutual building, Mumbai, Ashoka Hotel in New Delhi in the 1950s, the Dharwad college of Engineering in Karnataka, Topiwala National Medical college in Mumbai (carved in marble), LIC building in Nairobi and so on. He was involved in the creation of an installation at the J.J. School of Art and at Nandadeep Park in Bandra East (along with L. R. Ajgaonkar). He also created busts of personalities like Mahatma Gandhi, Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhai Patel, Bhulabhai Desai, his colleagues and even his own father.[27] Some of his decorative standalone pieces included the ‘Torso,’ ‘Deer,’ ‘Standing Woman’ and the bronze ‘Head’ which demonstrated his skill in chiseling and sculpting simplistic yet elegant forms, several of them winning him awards and prizes.[28]

The diverse range of Pansare’s work can be seen in his themes and subject matter – apart from architectural relief work and standalone pieces, he was also the designer of award trophies such as the Angel Face Trophy, the Music Composer’s club award and the ‘Black Lady ‘ statuette given to the winners of the Filmfare award winners. The Filmfare Awards (hosted by the Times Group) is one of the oldest award ceremonies in India, held to honour excellence in the Indian film industry, similar to the Oscars. The award was first introduced in 1954 and was originally designed by Pansare under the supervision of Times of India’s art director, Walter Langhammer.[29]

Pansare was also active in the education sector (particularly in the field of fine arts) and was a member of various educational boards like the Board of Examiners and Moderators of J. J. School of Art, Government Grade exams of Maharashtra state; Board of studies and examination, Faculty of Fine Arts, M. S. University; Syllabus Committee of Pune University; Advisory board for the Indian Institute of Industrial Design, New Delhi and the Hansa Mehta committee for the reorganization of art education in Maharashtra.[30]

Pansare’s Marathi identity manifested in his statue of Shivaji Maharaj, who is regarded as a prominent historical and cultural icon of the Marathi community. His identity of belonging to the Marathi community was reinforced by his neighbourhood and social circle. Initially living in Dadar (as did his siblings), he later moved to Kalanagar, Bandra, both areas known for its large number of Marathi residents, presence of eminent artists, politicians and even sportspersons from the community. While his siblings lived in Hindu Colony, Dadar, Pansare and his family resided in Shivaji Park, home to luminaries like writer and educationist P. K. Atre, mentor and cricket coach Ramakant Achrekar and many others. True to its name, Kalanagar, Bandra, was developed primarily as an artists’ colony in 1960-62.

Pansare was also the creator of the Maharashtra State award for Marathi films.[31] According to Kiran Pansare, his father was always surrounded by contemporary and eminent artists including V. N. Adarkar, Kamat, Karmarkar, Jog and Artre. Pansare’s Bandra studio and home was built in 1960 and he shifted there with his family in 1965. He recalls his father’s colleague, potter and fellow sculptor, Lakshman R. Ajgaonkar, fondly referred to as “Ajgaonkar kaka”. Together, the two of them designed and constructed an approximately 12-14 feet tall Laman Diya in Nandadeep Park in Bandra East in 1960 or 1962. A Laman diya is a traditional lamp commonly used in Hinduism. It was built on a large base with a peacock sitting atop the diya. It was named the ‘Yashwant Laman Diya’ and made of either stone or cement, can still be seen today.

A sudden heart attack on 24th May, 1968 led to his premature death – he was 57 years old. He found success as a sculptor and carved himself a legacy that would last for many years to come. One wonders what new creative expression and works he would have showcased to the world, if not for his untimely passing.

The lasting impact of his works on modern and contemporary Indian art can be seen from the representative exhibitions held by the Government of India around the world in places like Russia, United States of America, Europe and Scandinavia, in honour of his contribution to the Indian art and architecture scene;[32] an advertisement of the New India Assurance building was also issued in ‘The Times of India.’ The testament of his impact is witnessed even today. Salma Pansare (daughter-in-law of N. G. Pansare) recounts the reverence shown by ‘Shivaji lovers’ towards the Pansare family when they visit Shivaji Park. He is also known to have been a mentor of sorts to other sculptors such as Pilloo Pochkhanawala[33] and Adershir (Adi) Davierwala,[34] both eminent artists in their own rights.

In person, he was known to be jovial, witty and affable, with an excellent sense of style; he was loved by children , who fondly called him “Nana Pansare.” On the one hand he associated with prominent politicians and other dignitaries of his times, but on the other, he would chat with neighbours and children for hours. He was not one dimensional but possessed – as Kiran Pansare put it in the title of his article – a multifaceted personality.

The socio-political landscape of Mumbai is dynamic and constantly transforming. It is quite facile for art and architectural pieces of historical significance to be disregarded and swallowed by chaotic redevelopment while assertion of newer identities are reflected in the modern steel and glass tower. As long as the structures remain preserved, the artistic value of N. G. Pansare’s work and his place in history will remain carved in collective public memory, never to be forgotten. We owe that to him and his work.