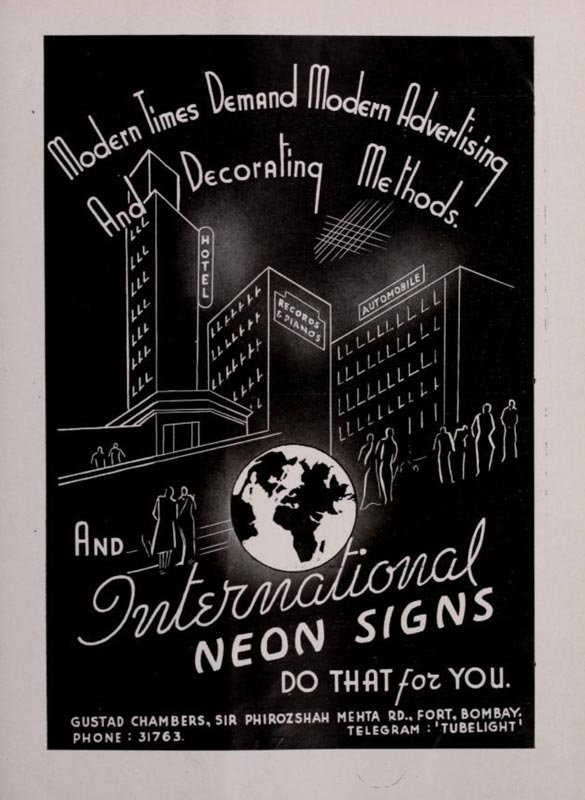

The emergence of this amorphous category of people also coincided with greater strides in printing technology. Print production had arrived in India by the late 18th century, and colonial centres like Bombay, Calcutta and Madras soon became hubs where the technology flourished. By the early 20th century, print was an established medium for circulating discourses on modernity, and advertising became a novel site to reflect this messaging. The thrust of these advertisements was frequently about leaving behind an older world order, and embracing the ‘modern’. So much so that even advertisements about advertising underscored the importance of being in tandem with ‘modern times’.

But what did it mean to be ‘modern’? Was it simply a breakaway from tradition? The adoption of Western styles and ideas? Where did the idea of the ‘modern’ feature vis a vis class, gender, and emerging ideas of nationalism in early 20th century Bombay? These advertisements form an important site to explore the intersection of consumption and the various interpretations of ‘modernity’. Often, the target audience for these advertisements were members of the emerging middle class, especially readers of English language media. The discourses coming through in them were shaped by these middle class sensibilities, as much as they were shaping these sensibilities. The following essay is an attempt to explore some of these threads through a look at print advertising of consumer goods and experiences from the 1930s to the 50s. The advertisements being looked at largely appear in English language papers like The Times of India and The Bombay Chronicle, or popular film magazines like Filmindia, journals like the Journal of Indian Institute of Architects, and at least one brochure published by the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) in 1953. It is safe to assume that these advertisements did not emerge in a vacuum, therefore, providing a fairly illustrative glimpse into prevailing discourses at the time.

The ‘Modern’ Woman Out in the World

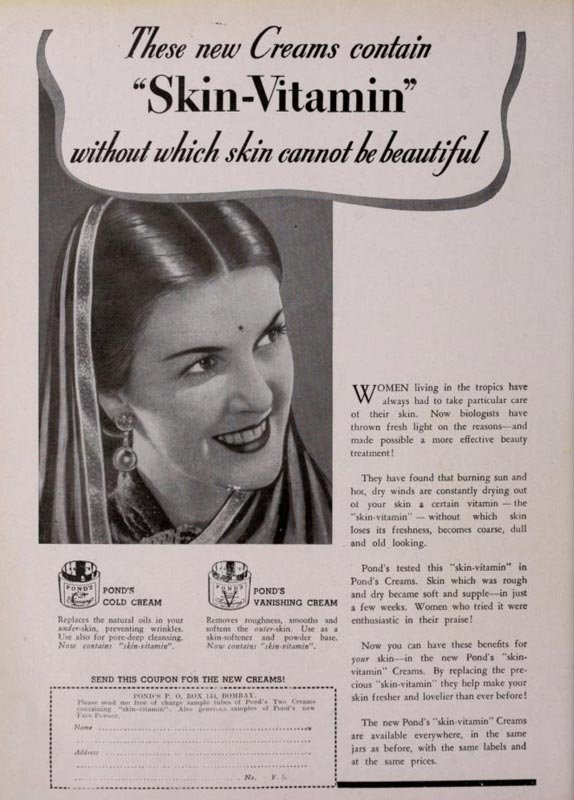

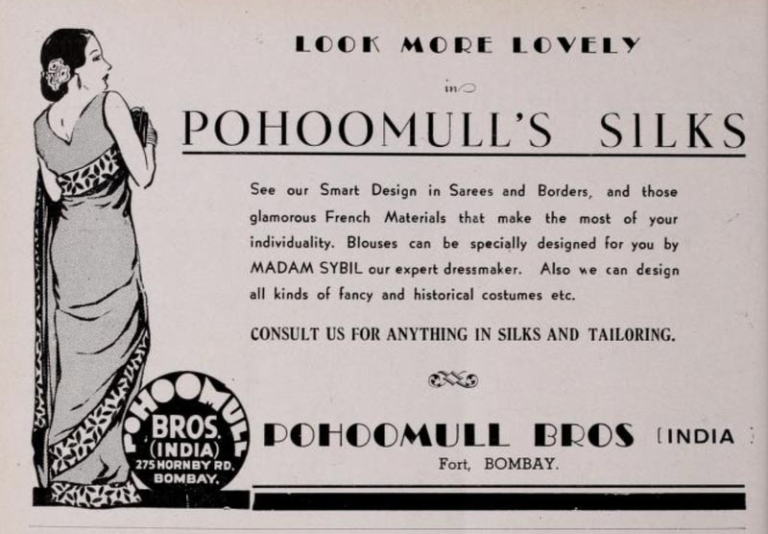

One of the most significant themes emerging out of the assortment of advertisements that were examined is the emphasis placed on ‘looking’ modern. This appearance was dictated not only by attire, but also by the products and goods one used. Especially for women, products like lipsticks, creams, skin lighteners, etc, came to be associated with “the expression of modern femininity”.[8] These new commodities, often separate from more ‘traditional’ home remedies and beauty treatments, also came to be associated with modernity itself, and new forms of freedoms and corporeal autonomy for women. [9]

The emphasis on women’s physical appearance is clear, as is the tendency to market beauty and wellness products largely to women, suggesting that these interests are reserved for a certain gender. But print advertisements and other visual media emerging at the time would also have been the first time women saw themselves represented in modern and vibrant ways. The images of these aspirations may have drawn from stereotypes, but they showed possibilities of constructing new selves and new ways to be. As women became the consumers themselves, they were addressed as the decision makers of not only their bodies and physical appearance, but also of their households, recognising their many roles as working professionals, mothers, homemakers, etc.

The Home and the World: Bombay’s Nationalism vis-a-vis Modernity

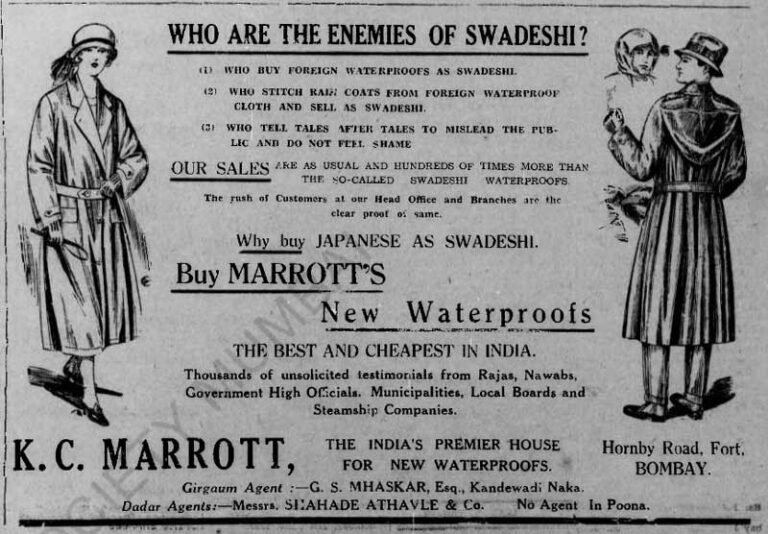

One cannot speak of emerging discourses in 1930s Bombay without a mention of nationalism, and the growing ‘swadeshi’ sentiment in response to British colonial rule. The city embraced several new ideas emerging in the West, and attempted to be a cosmopolitan conclave for Indians and European expatriates alike to enjoy amenities at par with the rest of the world. But it was also the headquarters for the Indian National Congress (INC) and the Muslim League – parties at the forefront of the independence struggle. Like in many economies around the world at the time, in urban India too, commodity capitalism and nationalism were simultaneous developments. This is apparent in the creative copies presented in advertisements, as well as in many commodities circulating in the market.

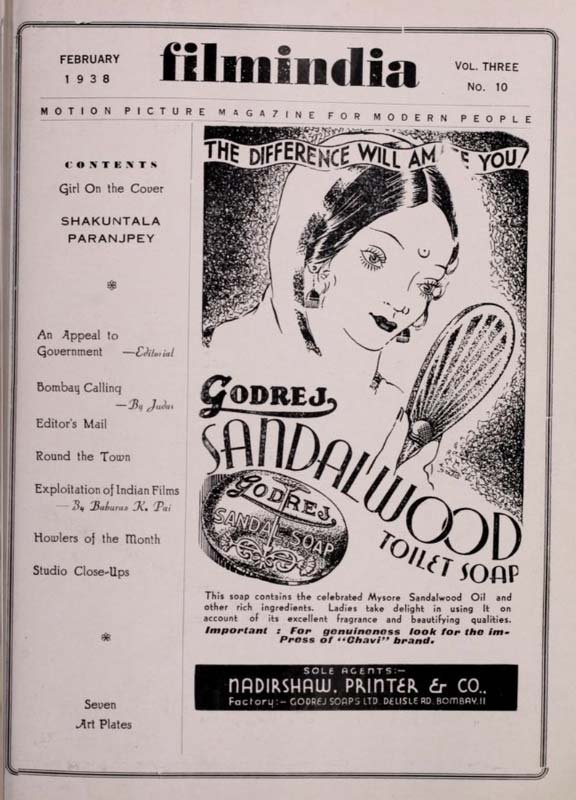

In 1918, Godrej Soaps Ltd., a renowned conglomerate today, was a homegrown company that introduced the first toilet soap made without animal fat (appealing to Muslim and Hindu consumers alike). The emphasis in Godrej’s advertising was often on the goodness of local ingredients, invoking the idea of the homeland through scents and fragrances associated with the region, like sandalwood and neem.

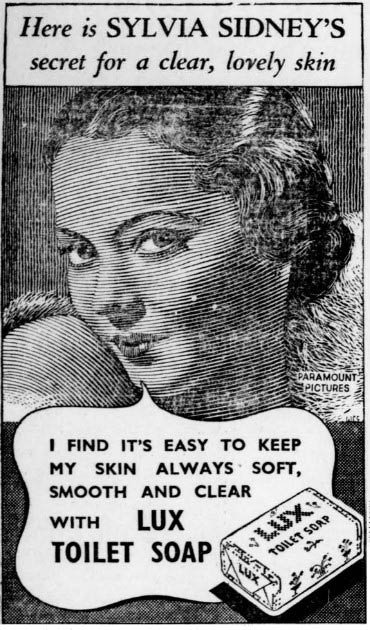

As Sabeena Gadihoke, in her seminal essay on the Lux star campaign has posited, toilet soap was a commodity categorically associated with “modernity’s global imaginary” and the various discussions surrounding public health and cleanliness.[16] Until the 1920s, a variety of items were used on the subcontinent to clean one’s body.

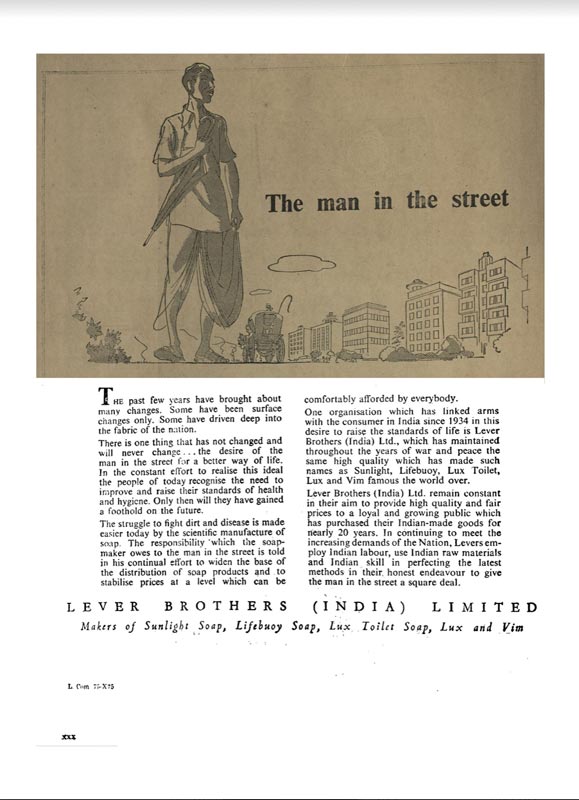

By 1953, Lever Brothers (India) Ltd. (known today as Hindustan Unilever Ltd.), in a spread within an MCGM brochure, declared itself unequivocally ‘swadeshi’, with an advertisement campaign invoking “the man in the street”. Published six years after Indian independence, the write-up in the advertisement looks to a “better way of life” with superior standards of health for the common man.

It is with the “scientific manufacture of soap”, claims the advertisement, that good health and hygiene has been made more attainable to the man on the street (the company was known for the manufacture of soaps like Lux, Lifebuoy, Sunlight, etc).

Lever Brothers (India) Ltd. was incorporated in 1933, after the growing swadeshi sentiment prompted the boycott of imported goods (Lever Brothers was a British company). Bombay, of course, was the favoured city to set up base for the company as Lever Brothers (India) Ltd., with its first soap factory established in Sewri. It is not incidental that the backdrop to the cotton dhoti and kurta-clad figure in the advertisement is a skyline with signature Art Deco-style buildings synonymous with Bombay, which also helmed the arrival of a new and cosmopolitan way of living, through the introduction of modern apartments. The visuals in the advertisement is an acknowledgement of the country’s newfound sovereignty, set against the backdrop of modern (read: better) living.

If the swadeshi sentiment often came through in the advertisements through these decades, so did the flipside — of foreign brands making a case for their legitimacy in the lucrative Indian market. An interesting entry from June 1933, in The Bombay Chronicle, is an advertisement by Marrott’s, which sold waterproofs or rain coats. The nearly argumentative tone of the advertisement calls out “enemies of swadeshi” – homegrown names that “buy foreign waterproof cloth and sell as swadeshi”. The implication seems to be that even within the swadeshi-driven market economy, there were duplicates that weren’t as ‘swadeshi’ as they claimed. “Why buy Japanese as Swadeshi? Buy Marrott’s” instead, asserted the advertisement. Here too, the figures in the spread are notable. The women, dressed in fitted waterproofs, don chic bob haircuts under cloche hats – the signature attire of the modern flapper woman in 1920s Europe and America. The advertisements for ‘swadeshi goods’, in contrast, often had men and women dressed in traditional attire, though the women’s nine-yard sarees were often traded in for the more modern six-yard version, as seen in the advertisement below for Currimbhoys. [19]

Modern Life in a City Carved Out of the Sea

So far, the advertisements above have shed light on the appearance of modernity through choices of attire, personal grooming products, and the complex relationship it shared with the nationalist rhetoric. But a large aspect of its emergence in Bombay from the 1930s also had to do with the shaping of a new city, carved out by pushing back the sea, i.e. reclamation, which in itself was a modern engineering marvel. The following sections delve into a few significant aspects of this modern city, with its new living quarters, spaces for recreation, and the embrace of a new lifestyle.

Modern Materials for Constructing a New City

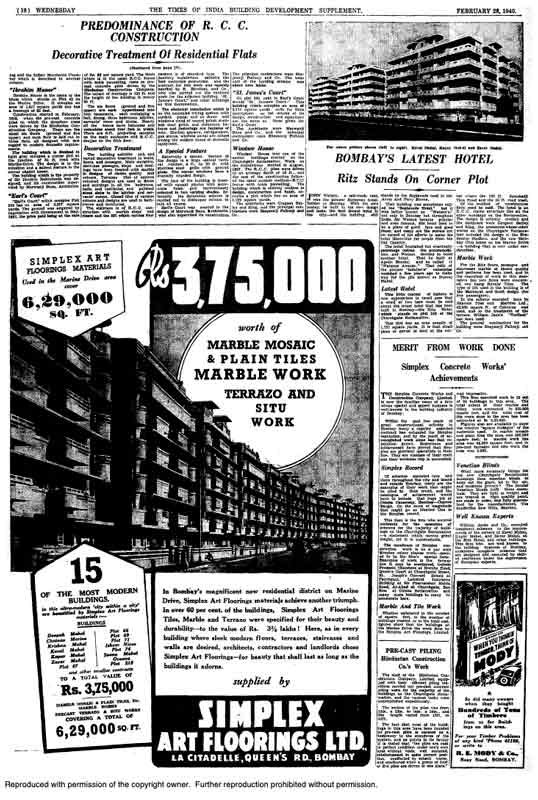

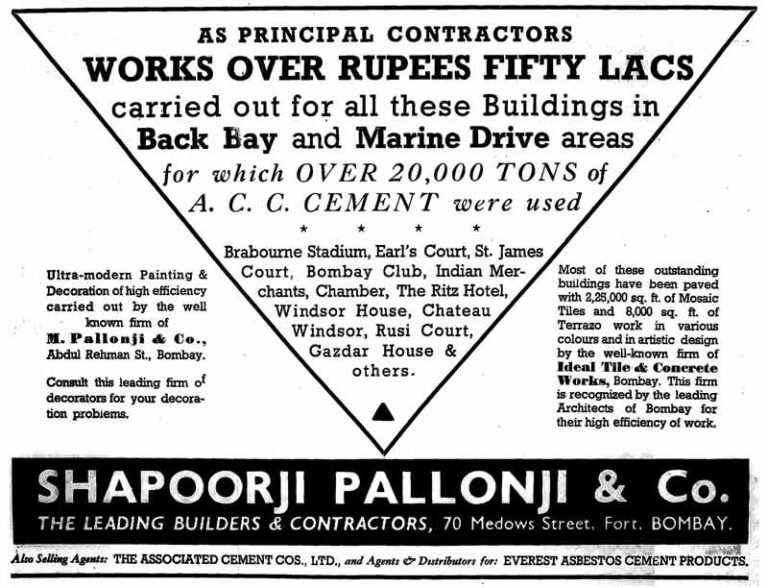

By the early 20th century, with the city already brimming with people drawn by the opportunities it had to offer, there was a pressing need to build spaces for this growing population to live in. Chawls were the obvious recourse taken by the newly constituted Bombay Improvement Trust, to house the incoming migrant population from the hinterlands.[20] The more socially mobile groups of people, often belonging to the middle class, however, gravitated towards the low-rise apartment systems developing in the city at the time. Newspapers like the Times of India carried multiple spreads and special supplements dedicated to these emerging residential systems, describing at length the scale of the developments, materials used, and the modern constructions they promised to be.

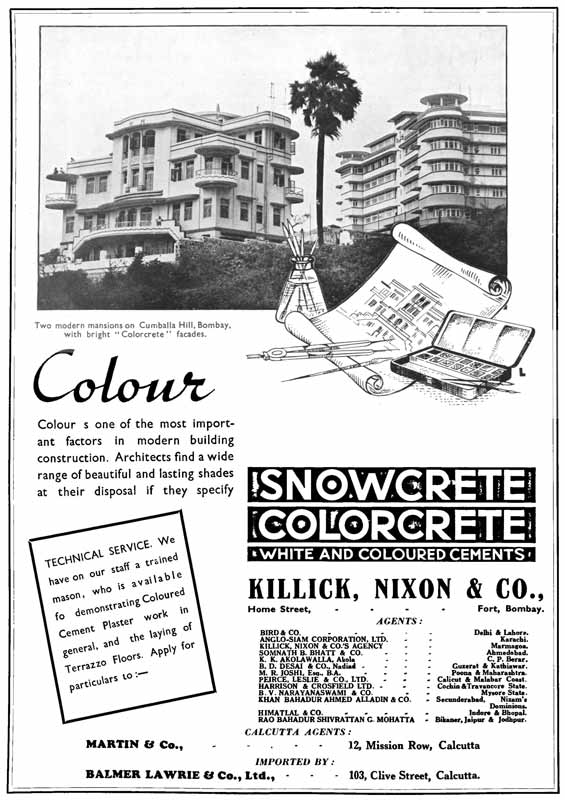

On the exterior, these Art Deco districts lent the city a streamlined look with their neat geometry, uniform heights and structural soundness emanating from concrete as a new material of construction. There was a spirit of constructing a new city with a modern outlook. Newspapers and other media at the time were replete with advertisements for cement, new building materials, tiles, paints, etc. Often, these were endorsed with the promise of an “ultra-modern” look, a clear shift in building styles, especially for homes and residences.

Tiles and coloured concrete were two products advertised heavily as modern construction materials. Colorcrete or coloured concrete was an innovative method of adding a pop of colour to building facades, while also giving it structural support. “Colour is one of the most important factors in modern building construction,” reads an advertisement by the company Killick, Nixon & Co., which highlights “two modern mansions” in Cumballa Hill.

An advertisement for Garlick & Co. screamed “modern floors”, with an illustration of the interiors of a home with a minimalist decor. “No modern home is complete without tiled floorings,” said another advertisement by the company. The “modern home” was at the heart of the conversation of a new kind of lifestyle in the city.

Apartment-Style Living

Apartment-style living brought about a change in the order, making space for the nuclear family to enjoy life in the city. The segregation of “zenana” and “mardana” (separated living quarters for men and women) was often done away with, the toilet came into the boundaries of the home (as opposed to being a separate unit outside the house for reasons of “purity”), and one’s neighbour in the next flat could often be of a different faith, nationality or caste (if not class). It engendered a cosmopolitan way of life, where one lived in their private, individual units, but there was scope for multicultural interactions by virtue of how these apartments were laid out. In contrast to chawls, which were often organised on regional and caste lines, apartments heralded a multicultural way of life, creating a new social structure in which neighbours could fraternise. As much as their development in the city signalled modernity, the interiors of these apartments were an equally important expression of one’s modern tastes.

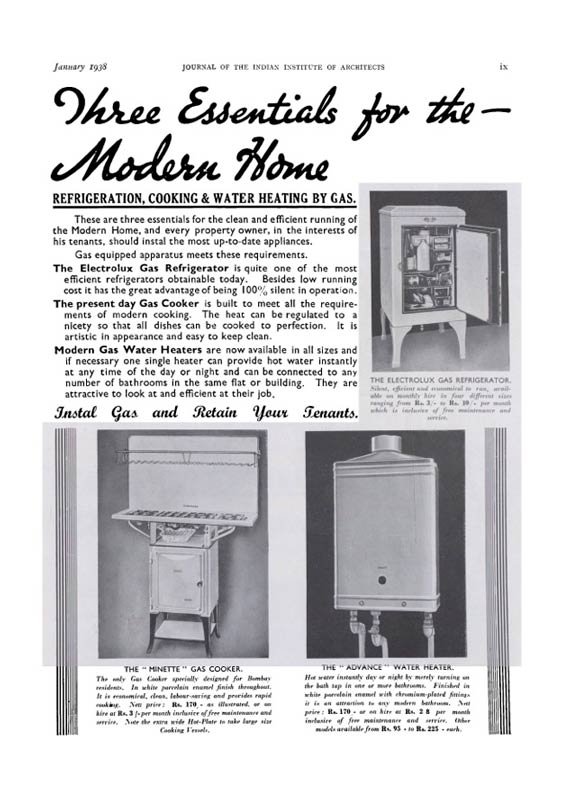

In 1937, the Indian Institute of Architects organised the Ideal Homes Exhibition, which was held in the Town Hall (known today as Asiatic Society of Mumbai). The exhibition was modelled on a similar event organised by the Daily Mail in London since 1908. It was a showcase of recent buildings erected in the city, architectural drawings, and most importantly, it contained models of fully furnished rooms that were befitting of a modern home. These rooms were also equipped with the latest appliances and tools to enjoy all the everyday luxuries of this new way of life. The exhibition envisioned the home with a cohesive idea of interior decoration, with pleasant colours and materials that were suited to the local climate, and all the modern amenities that would make a home comfortable.

“Home has an attraction of its own to a man returning after a day’s toil, whether for the rich or for the poor,” noted the editorial of the Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects published in January 1938. A well-decorated home was an indication of the owner being clued into the latest styles and international trends of interior decoration. Although, it was questionable how many residents of the city would have been able to afford the ideas proposed by an exhibition like this, it was a novel endeavour nevertheless.

There are a plethora of advertisements from the time that illustrate the types of homes that may have been considered aspirational. An advertisement put in The Times of India by The Novelties in 1937 went with the peg of making one’s ideal home “different”. “Modernise your home with a suite of Austrian steel furniture,” asserted the copy, describing it as a better option than wood for the city’s climate.

Another advertisement for Miller Cabinet Works draws attention to the work of “skilled Chinese carpenters” carried out under “European supervision”.

Women, again, became the focal point in many of these advertisements. A spread in a 1934 Times of India “Beautiful Homes” supplement describes the plight of the “average memsahib coming to India for the first time”, invoking the sensibility of the English housewife to make her new abode in India more “homely”. [24] The messaging in advertisements for interior decoration and beautification of apartments was frequently directed at women readers, the idea being that as homemakers they would spend a greater amount of time indoors (like the “average memsahib”) and would be the perfect candidate to be concerned with the aesthetics of the house. In another Times of India entry from a few weeks prior to the aforementioned spread, the various upgrades possible in the kitchen, from electric refrigerators to stoves, are highlighted. These interventions are proposed as modern conveniences, but the figures in the images, and who the copy is addressed to, are only women. Even in the modern home, gender roles seem to be dictated by traditional conventions.

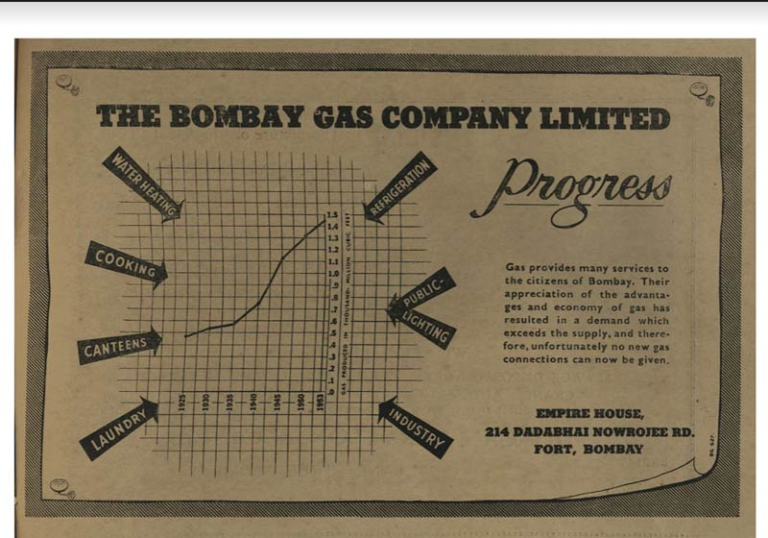

Gas was a significant modern amenity. Bombay Gas Company placed several advertisements in newspapers and journals of the time, making a case for refrigeration, hot water, and easy cooking with gas. “No tropical food problems,” declares one 1936 advertisement, referring to a shift in lifestyle as preserving food in Bombay’s wet climate became possible with proper refrigeration. The modern home could also be equipped with hot water on demand, allowing one the luxury of enjoying long, hot baths instead of just the functional act of ablutions. Many of the advertisement copies by the company draw attention to how sleek and good looking all the appliances are, and how they add to and enhance the aesthetics of the interiors.

By 1953, in an advertisement published in the MCGM brochure, the company is found announcing no more gas connections are available since “citizens of Bombay” have embraced this amenity so wholeheartedly, resulting in a “demand which has exceeded the supply”.

The Entertainment Realm

There were also new avenues of recreation emerging at the time. The radio, of course, was a modern amenity, not only in Bombay, but around the world. To be able to hear a disembodied voice over a radio frequency was a marvel of modern technology, and to have a portable console within the home was a novel experience. It often became the centrepiece in the living room, around which the family would gather for the evening news. A Times of India entry from November 1937, the day the exhibition opened, stated: “In fact, round this marvellous instrument can be built all kinds of afternoon and evening parties. If you have half a dozen friends to dinner, the radio will supply the background music to the cocktails, while during dessert it will give you the day’s news.” [25]

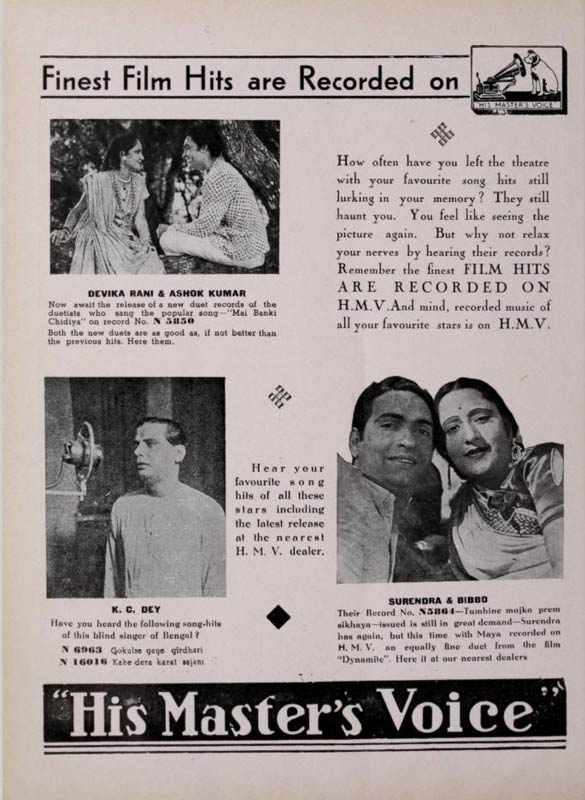

The following year, His Master’s Voice (HMV) put an advertisement in Filmindia with images of some of the most popular film stars of the time – Devika Rani and Ashok Kumar, Surendra and Bibbo, and K.C. Dey. “Finest Film Hits are Recorded on His Master’s Voice,” said the advertisement, with the iconic logo of the dog and the gramophone, as it encouraged patrons to take home their favourite film records to listen at leisure.

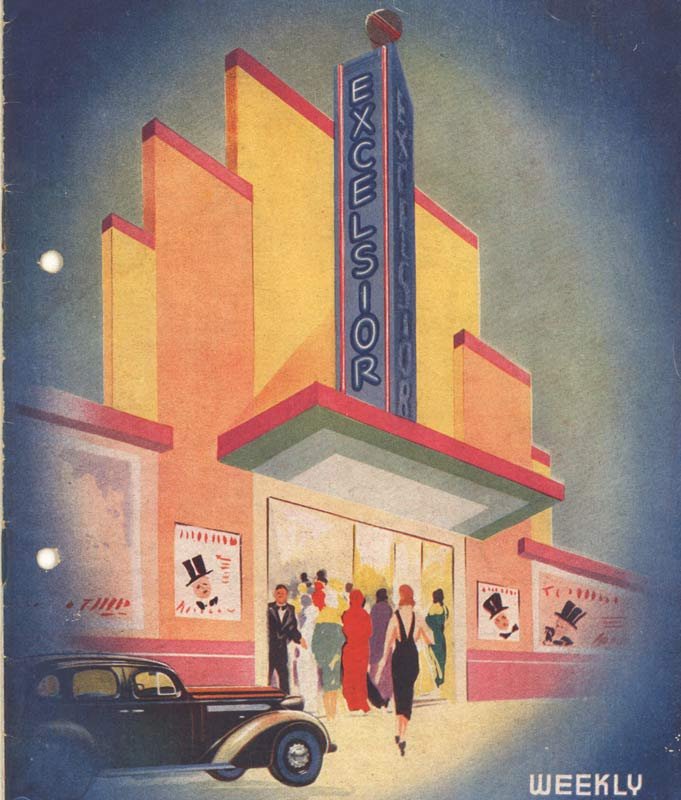

Cinema exhibition and filmgoing was another significant development of the times, shaping public culture and recreation in urban centres around the world. Bombay was no different. The 1930s saw the emergence of a variety of Art Deco picture palaces, as well as the conversion of erstwhile stage theatres into talkies. Newspapers had columns dedicated to show timings, and often carried special supplements that covered various aspects of a new cinema in town. The cover of a brochure published by Excelsior Theatre paints a glamorous picture of what a night at the theatre could look like in the early 20th century. There are blinding lights illuminating the theatre’s Art Deco facade, streamlined luxury cars, women and men wearing the latest fashions. These cinemas boasted of scientifically cooled air, the finest talkie equipment, and various aspirational luxuries that urban life could offer. Going to the cinema was an all-encompassing experience of splendour and leisure, beyond simply the specific film that may have been playing.

Similarly, modern ideas of recreation also extended to other aspects of life. A playful advertisement for Beck’s, a German beer popular to this day, combines the leisurely ideas of playing golf and enjoying a cold can of beer. Notably, a big part of the island city’s development was the emergence of several gymkhanas and sports clubs in the early 20th century, in particular Brabourne (now Cricket Club of India), the Art Deco-style stadium in Churchgate, which provided wealthy Indians with a space to practice sport for leisure. A new city had been reclaimed from the sea, and it was being designed with several pockets of leisure and modern recreation.

New Ways of Being Mobile

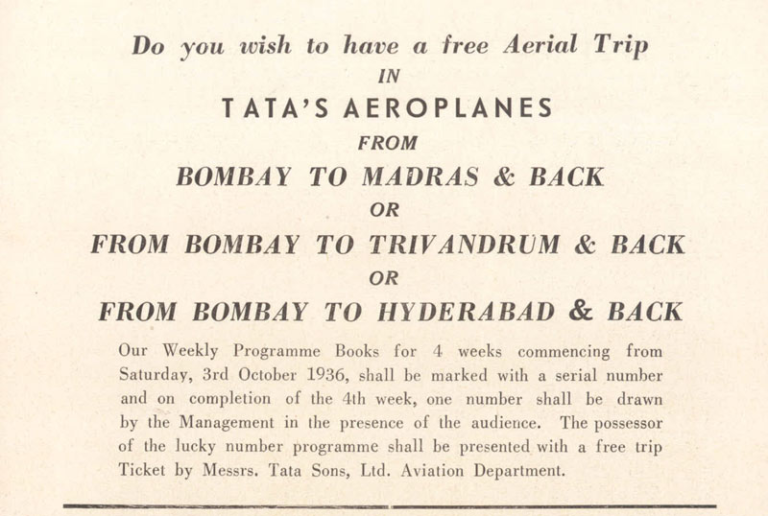

Mobility is one of the defining themes of the modern age. The 19th and early 20th century saw developments that dissolved international borders, allowing the travel of people, goods and ideas. The Indian Railways were established in 1836. Three decades later, the opening of the Suez Canal considerably reduced the travel time between Britain and India, bolstering trade between the two shores. By 1903, the Wright brothers had successfully powered the first aeroplane. As significant preoccupations of the modern age, speed and mobility were also reflected in the city’s built environment. In the Art Deco style, one can see motifs referencing these new modes of travel, with turrets resembling ocean liners or streamlined balconies that looked like locomotive engines.

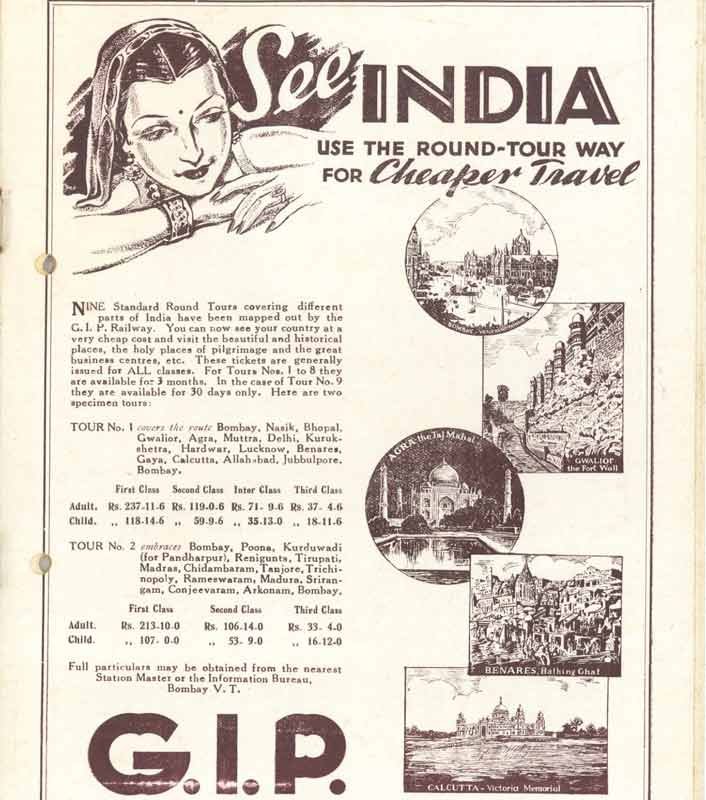

In contrast to flying, railways were a novel but relatively affordable means to travel. In fact, Bombay was chosen as the starting point of the first passenger train in the Indian subcontinent, in 1853, which ran between Bori Bunder (later rebuilt as the Victoria Terminus) and Thane. By the 1930s, it became possible for ordinary citizens of Bombay to travel India for leisure. GIP or the Great Indian Peninsula Railway (now the Central Railway) took out packages for tours starting in Bombay, heading north towards Delhi, Benares, and Calcutta, or heading south towards Madras, Tanjore and back. These tickets were available to all classes of passengers. Again, notice the figure in the advertisement – an unmistakably Indian woman, seemingly lost in thought at the idea of being able to voyage through India, a convenience accorded to her by modern railroads and infrastructure.

Modern living, of course, is incomplete without the personal vehicle.

While not everyone could afford an automobile, the city nevertheless welcomed several luxury automobile companies to set up workshops. General Motors, Ford and Premier Automobiles had all established shops in Bombay, and one would often see cars like Buick and Chevrolet being driven down the Marine Drive promenade.

The electric tram fulfilled the need for public transport in a growing city, with double-decker tram cars being introduced by 1920 to accommodate the density of passengers.

Today, it seems impossible to imagine the city was once connected by a thriving tram network. But the system did shape the infrastructure of the city, with the circular gardens at Sion, Dadar and Kings Circle acting as the last stop for the tram line. The local train network, arguably the nerves and sinews that feed the metropolitan city of Mumbai to date, also emerges by the early 20th century, allowing people to travel far greater distances. It is in this period that the adage “the city never sleeps” is being realised. Bombay, the hustling city, fostered opportunities, dreams, innovations and negotiations required to make life possible on its shores.

A way of life was being envisioned, much of which was fashioned around aspirations of modernity, or at least what one believed to be modern. ‘Modern’ became a catch-all term that also carried within it several complexities and contradictions, whether it be the degree of new freedoms accorded to women, the idea of a cosmopolitan city that was also the site of a burgeoning nationalist struggle for independence, and an emerging middle class that largely spoke the language of the coloniser – a tool of negotiation, in some ways, used to ascend in the social hierarchy.

In Conclusion

Many of the advertisements surveyed above were for brand name products, targeted largely towards the urban middle class in the city. Identifying as a member of this heterogeneous class often meant the rejection of vernacular practices as unscientific or backward, instead embracing ‘modernity’ by consuming branded commodities, frequently imported from overseas or manufactured in large urban centres like Bombay. [27]If in some of the earlier advertisements, these fantasies looked foreign, often with European-looking figures, gradually they started to give way to more obviously Indian-looking figures – as if to say Indians too could partake in these fantasies now. These fantasies included the possibility of urban professionals enjoying leisure activities like visiting the theatre, promenading at Marine Drive, decorating their flats in the latest fashions, etc. While the degree of consumption may differ based on an individual’s purchasing power, what remained common for all those attempting to identify as middle class was the act of consumption itself.

At the heart of ‘modernity’ lay the end of an old order to embrace new technologies, commodities, attitudes, and ways of life. These advertisements positioned home products, construction materials, recreation, and the apartment itself as this way of life – an all-encompassing lifestyle that defines the city to date. It became the perfect conduit for those looking to rise in the social hierarchy, by taking on various aspects of modern life and fashioning a new class category. In an ideal modern world, older stratifications of caste and class ceased to be relevant. A modern city, like the one Bombay was emerging to be in the early 20th century, could be a site of dizzying aspirations, alienation and hardships. But it was a polyglot nevertheless, a new city, where anyone was welcome to adopt new ways of living.

Suhasini Krishnan for Art Deco Mumbai

Suhasini is a writer and journalist based in New Delhi, with an academic background in Film Studies and History. Her research interests lie in cinema, modernity, and the making of an urban city.