Established in 1934, Kamdar Karyalaya (later Kamdar Private Limited) emerged as one of Bombay’s most sought-after firms for bespoke furniture and interior design, known for a fine balance of craftsmanship and functional design. The firm was founded by Bhagwandas Kamdar, and grew in stature with the arrival of German architectural designer Ernst Messerschmidt, whose association with the family business from the mid-1940s until his death in 1974 shaped a signature design language. From luxurious homes to landmark hotels, the firm’s work defined what stylish living looked like in a newly independent India. Elegant, well-proportioned spaces with custom-made furniture that often blended Indian sensibilities with European aesthetics. Over decades, Kamdar’s portfolio came to include marquee names: the Taj Hotel, Air India offices, Mafatlal residences, and iconic restaurants like Volga and La Bella. With each project, the Kamdars delivered not just high-end furniture but an integrated interior experience, one where lighting, murals, cabinetry and even home bars were designed as part of a coherent vision.

Their pieces were often crafted in teak or rosewood, finished with painstaking detail, and tailored to Bombay’s changing lifestyle – from concealed bars in bachelor pads to classical carvings in drawing rooms meant to entertain. It wasn’t unusual for Kamdar furniture to become a household name, remembered fondly by generations who grew up with it, or as a byword for discipline among children warned not to jump on “Kamdar sofas”.

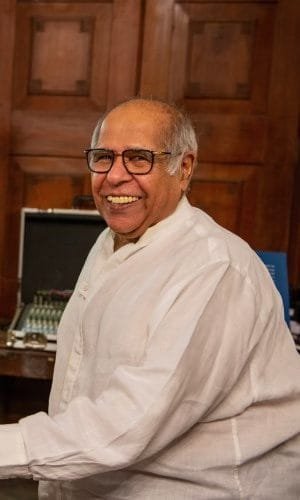

In this conversation, Vikram Kamdar (born 10 December 1943), son of Bhagwandas Kamdar, shares recollections of a Bombay that is at once personal and professional (with additional insights from his wife, Nandini Kamdar).

Having joined the family business at the age of 22, Vikram worked across the firm’s drawing departments, factory floors, and client meetings, gradually expanding its reach and preserving its archive. Through his memories, we uncover not just the story of a firm, but a layered account of Bombay’s social and spatial transitions. This is a story about design, but also about legacy, friendship, and a city in transformation. Excerpts:

What can you tell us about your father’s background, and how he started Kamdar Furniture?

My father was a civil engineer. He studied at the engineering college in Pune and passed out in 1926. After graduating, he worked with the government as Assistant Engineer in the Nashik district. But that was the time when there was a lot of Quit India, and my grandmother was active in the movement. So he left government service as he did not wish to continue working for the British, and decided to start on his own. He started woodworking, which was his passion. He began making wooden articles for montessori and kindergarten classes.

I believe the first furniture order he got was from Mr Birla, his neighbour at Nepean Sea Road, to make a dining table. That’s how the furniture work started.

How soon after quitting the government job did he start Kamdar Karyalaya?

Kamdar Karyalaya was started in 1934, but he probably began making the wooden toys a couple of years earlier. In 1938, we moved to a factory in Byculla. Around 1940, we shifted into a building of the Industrial Assurance Company [opposite Churchgate station], where a Mr Setalwad was the chairman. We were the first tenants. The ground floor was our showroom and the upstairs housed our offices and design department.

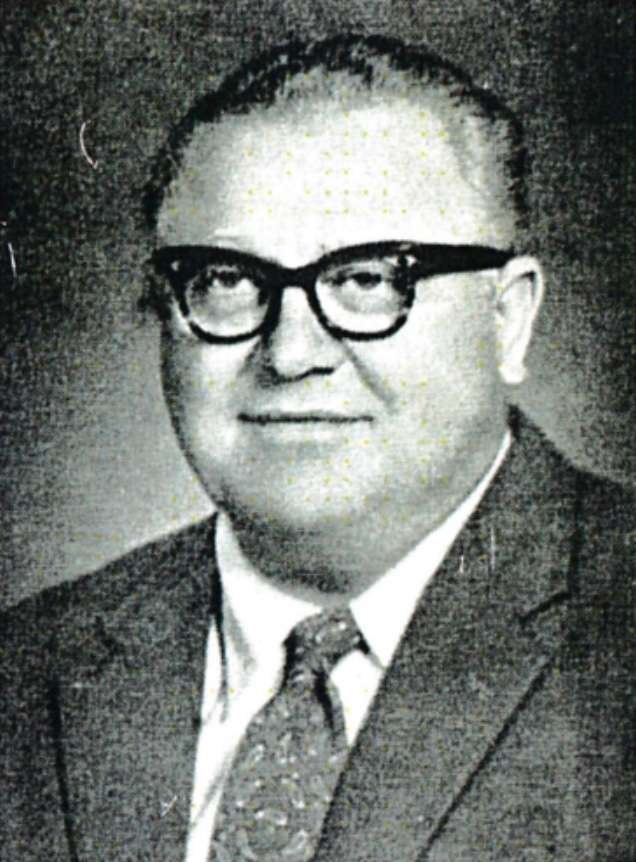

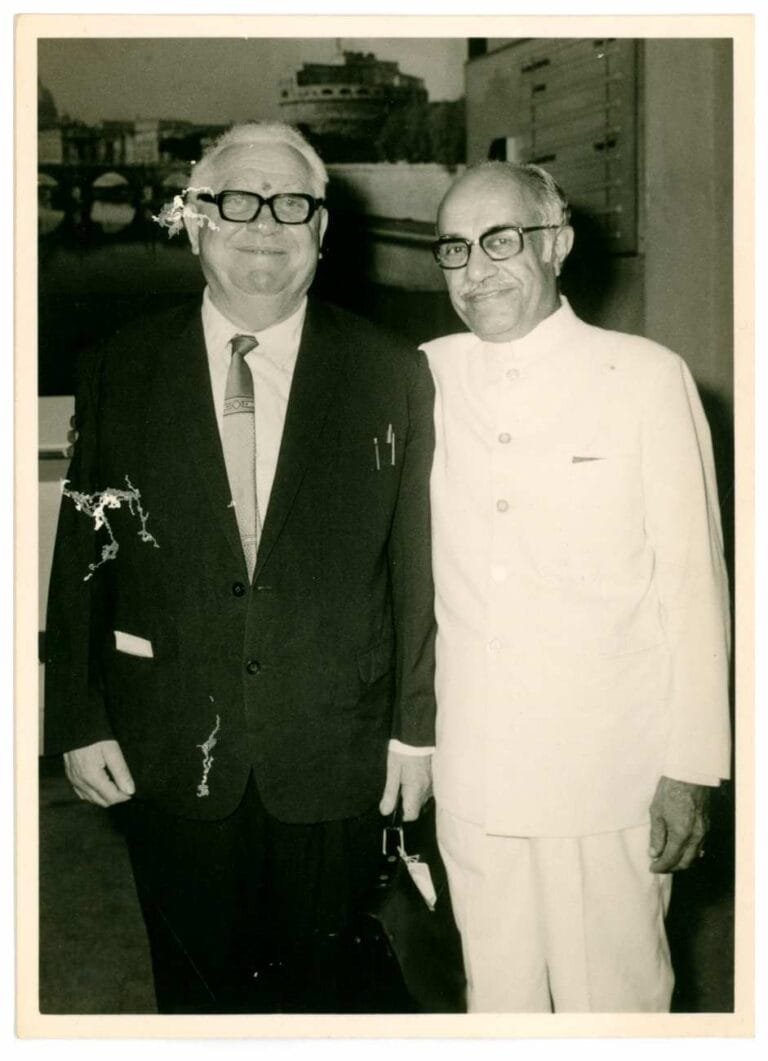

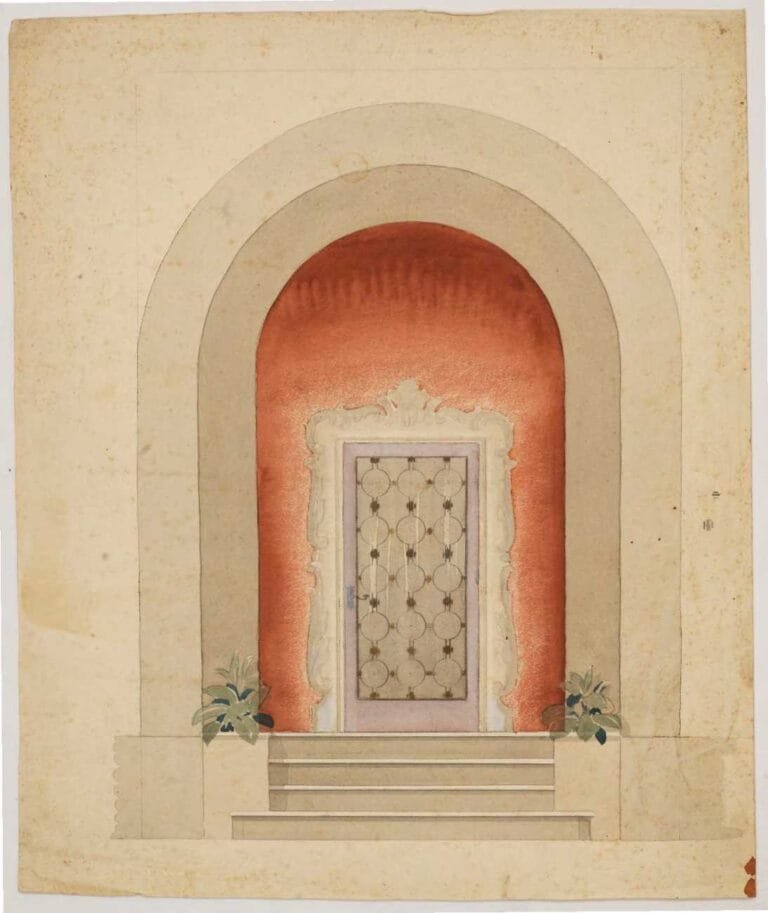

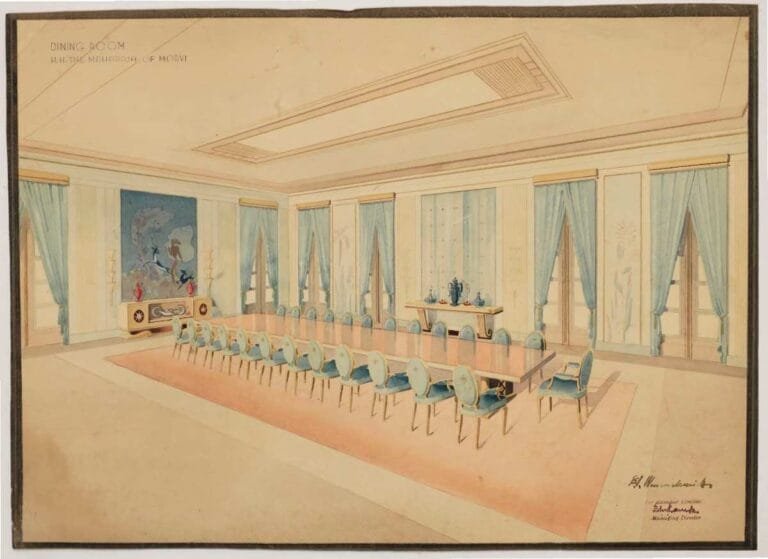

We had a good design department. Initially, our chief designer was Mr Dhurandar. After the war, we had a German designer, Mr [Ernst] Messerschmidt, a German interior architect who had come to India to work on the Manik Bagh Palace in Indore. After completing it, he returned to Germany but was called back to design the nursery. Before he could return [to Germany], the Second World War broke out. He was interred in a camp in Dehradun. Someone told my father about him and suggested we send him work. After the war, with his village now in East Germany and having lost much of his family, he chose to stay in India.

My father invited him [Messerschmidt] to join the company. This was around 1945–46. He was like a brother to my father and a second father to me. We grew up together. The design narrative of Kamdar was set by him.

Given there weren’t any interior design courses in India back then, was it Messerschmidt’s formal training that first caught your father’s attention?

There were no architecture courses back then. I did architecture at Sir J. J. College of Architecture starting in 1960, and even then, there were only about three colleges in India. There were no interior design courses. Our designers mostly came from the Applied Arts. Messerschmidt had studied interior and architecture in Germany, and was a seasoned designer. Today, you have decorators, designers, and interior architects. But back then, we filled all those roles. Even though I would have preferred to study interior design, there was no such course, architecture was the closest option.

You worked closely with Messerschmidt as well?

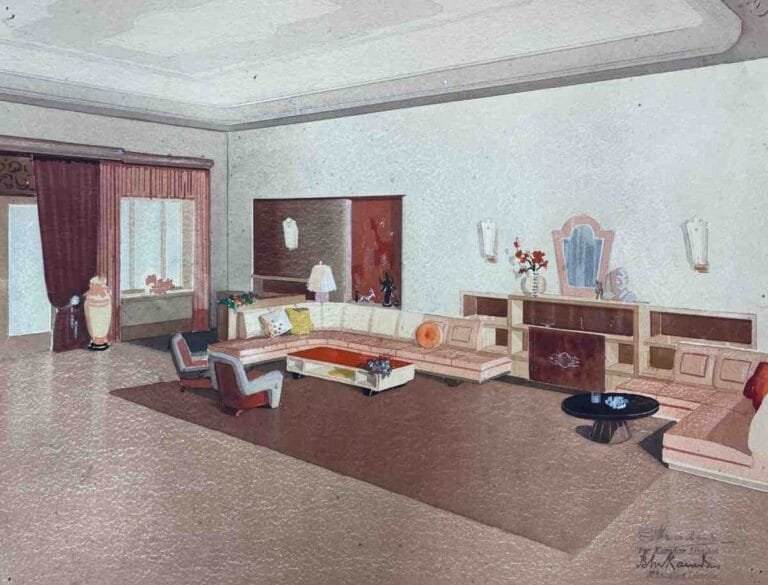

During my vacations, I worked in the design department, doing hand drawings. Even today, I don’t know CAD [Computer Aided Design]. Our designers show me work, and I say, “Listen, give me a scale.” Messerschmidt taught me watercolour presentations. We had specific colour themes, and we worked across residential, commercial, and hospitality. Designing and fitting all three was our speciality.

What was your first role in the company?

I started in the drawing department. Eventually, I had to take on broader responsibilities. Around 3-4 years later, I started going to the factory regularly. Over time, I began overseeing everything, and the scale of operations gradually reduced. I think I was in the drawing department around the time Messerschmidt passed away in 1974.

What was your father like at work?

He was meticulous and dedicated. He would see everything through.

Doing customised furniture meant every client was a new project, there was no standardisation of furniture, you had to meet with them and everybody had a new personality. He built close relationships with clients, and they became friends. At 7 a.m., he could get a call “Please come and hang a painting.” We were like family doctors.

I remember that wherever we worked, we transported our workers as you didn’t have many skilled workers. In Bombay, we did a lot of work for the Taj. JRD [Tata], my father worked on his house and office. He also did work for Nani Palkhivala, the economist.

Your father is credited with designing Sudha Kunj, a striking Art Deco bungalow in Tardeo. How did this collaboration take shape and was it the only building that your father ever designed?

He also did Maheshwari Mansion at Nepean Sea Road, but it is broken down. In those days, many civil engineers also took on the role of architects. There were quite a few who weren’t formally trained in architecture but handled both. The Mariwalas [owners of Sudha Kunj], who were part of the same small community as us, had a family connection.

[Nandini Kamdar: Many of these homes had Kamdar furniture. Most of them were either friends or relatives, and Jaysinh Bhai [Jaysinh Mariwala] would often say that whenever the children jumped on the sofas, someone would exclaim, “Kamdar Kaka losna,” meaning “Kamdar Uncle is going to scold you!” They were so scared, that was the only way to make them stop.]

What do you think was the turning point for Kamdars, in terms of becoming a household name?

The silver jubilee in 1958-59 was a milestone. But really, after Independence, around 1952–53, things picked up. People wanted to build and live better. But the Emergency in the 1970s was a tough period, worse than the COVID lockdown. People stopped spending for fear of raids. The most inquiries we got were people asking us to issue backdated bills for furniture they already owned.

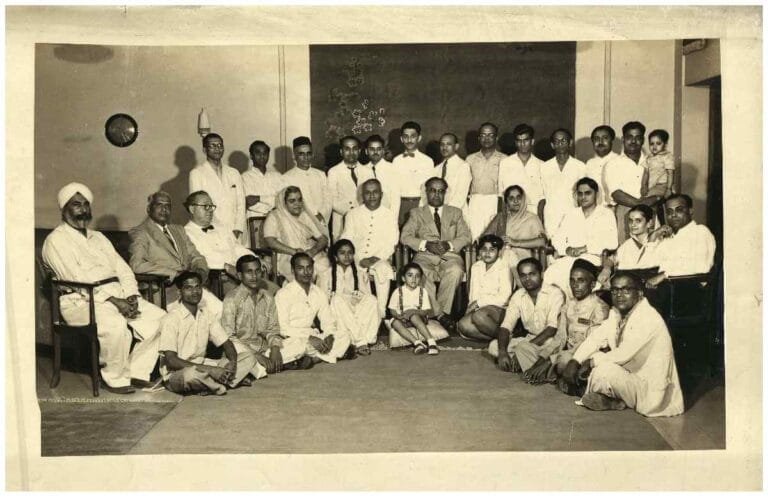

I want to go back to the beginnings of the company. How many people were there in the company to begin with?

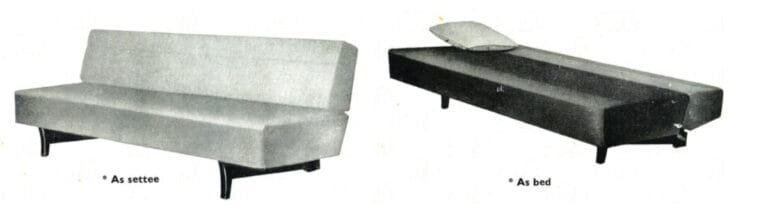

We had about 12 designers in our studio, 4-5 in accounts, and around 150 people in the factory – carpenters, upholsterers, polishers, machine operators. The grills and locks were made in-house. Some old cupboards from the 50s-60s still have Kamdar-stamped keys. Each wardrobe handle was designed by Kamdars. We were the first to introduce the zigzag spring and the single sofa-cum-bed, we still have the first piece. It was called Kamette.

And typically what materials would go into making the furniture?

We only used solid wood, no plywood. Burma teak came in as whole logs through the Burma Trading Company (BTC) at Sewri. The logs were stored in water to prevent drying. We selected them ourselves, checking size, girth, and quality. Then they went to Sundardas Sawmill near Reay Road.

We told them how to cut it, then stored it in our factory with air gaps for seasoning. From purchase to use, the process took 7–8 months. The longer it’s kept, the better the wood becomes because it stabilises as the water content drops. Seasoning allows the wood to settle and resist warping. Initially, we relied on natural seasoning, but later on, we sent timber to seasoning plants that steamed the wood to speed up the drying process. Everything we made in those days, wardrobe shutters, table tops was solid wood. Large planks of three-quarter thick timber were joined, and they remained that way. I still have a solid rosewood table upstairs.

Where did the artisans come from?

We had many Sikhs. The best ones, strong, skilled, were from Saurashtra and Uttar Pradesh. Our chief craftsman was a Sikh too. Most of our carpenters were from Gujarat and north India.

How much time would a Kamdar piece take before heavy machinery came in?

At least three months. These were all specialised, handmade items not machine-processed. Bolstered furniture took even longer, as each piece was a new design. Our design department prepared scale drawings, and in the factory, the upholstery supervisor created full-size drawings. He would then make templates which were used by carpenters to cut shapes. We would test for comfort and label the templates for future use. Today, CNC [Computer Numerical Controls] machines do this in seconds. We made detailed, precise working drawings. I remember working for the Oberoi Hotels when they first started. The American architect Dale Keller, based in Hong Kong, sent us drawings that included the exact angle of screw insertion. It was daunting, everything was structural.

Could you elaborate on how colour influenced your approach to interiors, particularly when it came to upholstery and the dyes used?

I recall that velvets were widely used at the time especially from ELDEE Velvets. We also sourced moquette, a special type of weave that came from Gujarat, along with a lot of leatherette. There was a company which produced what was known as rexine, that became a trend everyone wanted to use. There was also a phase when wall-to-wall carpeting was in fashion. We used to design custom carpets tailored to each interior. For example, for the Mafatlal family, we designed upholstery fabrics specifically for their sofas. These were specially woven in Banaras using silk and included detailed work. We did something similar for B. R. Chopra [notable Indian producer and director, elder brother of Yash Chopra]; their entire bungalow was done using brocade, which only came in 28-inch widths, so we had to carefully plan how to use it.

Kamdars was doing a variety of things; you were also doing manufacturing, design. So, who were your frequent collaborators?

Initially, we designed our own light fixtures, even the locks. Later, we began sourcing fixtures, often from a company called Terra Trading, which was quite prominent. We also worked closely with timber and plywood suppliers, including the Mafatlal group. For decorative elements like domes and rosettes, we collaborated with Kalabhai Karson, a very skilled artisan known for his intricate curves and plasterwork. Sadly, he’s no longer around. I recently spoke with his son, who mentioned there’s no longer any demand for that kind of craftsmanship. He now sells Plaster of Paris for dental work, a complete shift from the artistry his father was known for.

There were also specialist mirror suppliers. Since we were early adopters, many vendors offering new materials approached us to test and use their products. We gradually phased out office interiors as open-plan layouts became the norm. Cabins were no longer being made. The only office work we continued was for boardrooms or managing directors’ cabins. We used to make office chairs, but now we’ve scaled back and only handle the furniture side, and that too occasionally.

Kamdars is a pan-India name, so what was your advertising strategy?

We didn’t advertise, everything was by word of mouth. Over time, we realised we had to adapt our marketing strategy slightly, though we continued with custom work. The major shift came with the launch of the Kamette, which was our first standardised product. It was so successful that we had to introduce assembly-line manufacturing. Kamette was the only product we made at that scale. When television became more popular, we also did a few TV advertisements.

The Kamette set became a household essential in joint families. It served as an extra bed at home and even found a place in offices. Executives would say, “Just give me one, because I want to have a 20-minute nap, after my lunch.”

What were some of the big projects under Messerschmidt in Bombay?

One of the key projects was at Taj Mahal Palace. We designed the Rendezvous restaurant. It was one of the most beautiful spaces. It was originally on the ground floor, though the layout has since changed. Back then, the Taj’s new building hadn’t come up yet. In fact, between the old and new Taj buildings was a lane, and in that lane stood Green’s Hotel. There was an entrance from the lane that led into Rendezvous. We also worked on the Harbour Bar, which still partly exists. Then came Golden Dragon and Wasabi on the upper floor. The main bar area from that time still exists today. All of this was under Messerschmidt.

We handled everything for the Mafatlals, their offices and homes in the 1970s. Even earlier, we designed industrial homes for the Birlas, Tatas, and Mafatlals. We also did many restaurants, Volga, Napoli, Alibaba, and La Bella, which was located where Fabindia is now, in Kala Ghoda. These were classic establishments with bandstands, dance floors, and cabarets. We also worked extensively with Air India. Their offices were opposite the High Court. Another big area was the mill shops Finlay, Khatau, and others. These were beautifully done retail spaces. Unfortunately, with the collapse of the textile mills, that chapter closed. Still, they were some of our most noteworthy projects.

Was he [Messerschmidt] ever a partner?

No, he was always employed. There was no formal partnership, at least not that I remember. He had everything: a car, a driver. He wasn’t treated like just an employee. He was like a brother to my father.

When we look at the 1930s furniture, rich velvets, curved forms there’s a distinct Deco sensibility. Were these design elements something your company consciously brought into the interiors, or were they aligned with broader public tastes back then?

Yes, it was mostly for those who wanted something classical. I think the demand was stronger in favour of French styles. We did a lot of carved furniture during that time. Each carving was carefully researched to ensure authenticity, and then executed with precision. What was more in vogue was post-modern and French classical. Victorian styles were rare. And when we talk about interiors, it wasn’t just about standalone furniture pieces, it involved the full design scheme: wall colours, lighting, carpets, everything came together to define the space.

[Nandini Kamdar: There was also the concept of home bars. Initially, people were conservative and hesitant about such things, but over time, alcohol began to be served at home. These bars revolved around and could be concealed because people didn’t want the bar to be visible.]

We also did an entire home on Pedder Road at Alpana, for a young bachelor. He was a racing car enthusiast and had a Hollywood actress friend who helped design the bar. It featured a mural of Marilyn Monroe behind it.

You’ve also been very careful about archiving drawings and designs. Was that always part of the practice, or did it evolve later?

Initially, we just held on to old drawings as part of our practice. It really started when designer Ritu Nanda visited and saw the drawings. She suggested that these should be archived. We went on to digitise all our drawings, about 500 working drawings. Each one has coloured documentation. It’s all preserved now for future use. Everything new builds on what existed before whether in science, history, or design. Knowing the past helps inform the future. That’s what we want to do now: make this knowledge accessible and adapt it to new technologies.

I hadn’t even realised that Art Deco extended into bathrooms design details carried into every part of the house. It wasn’t just the formal rooms. The idea was to bring beauty into every space.

How were these scenes and drawings made?

There was a clear method to it. We began with pin drawings, decided the eye level, and then built the full scene. The layout plan came first, followed by designing and constructing the furniture.

Initially, everything was drawn on tracing paper, and the lines were then transferred onto watercolour paper. That paper was stretched on a board, taped, and given a water wash so it could absorb the moisture. Once dry, only the linework was transferred and no pencil marks would remain. A key principle in watercolour work was that white wasn’t painted in; what you see as white is actually the untouched surface of the paper itself.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Churchgate Street, where your showroom is, was also known as Jazz Street, with a vibrant nightlife. Do you recall that period?

The Ritz Hotel had a restaurant called Little Hut, and Astoria had The Venice, which hosted regular jam sessions. A well-known singer named Bittu used to perform here. Gaylord’s, a residential building, housed a restaurant called Blue Gardenia furnished and designed by Kamdars with interiors that reflected its name, in blue tones and gardenia motifs. Parisian Dairy, later taken over by the Narang family [owners of the Ambassador Hotel], also added to the scene with karaoke nights before it transformed into Jazz by the Bay and eventually Pizza by the Bay. And in Rehmat Manzil, there was a restaurant where I used to have a four-course lunch meal for 7 rupees. A soup, a main dish, starter, dessert, coffee.

Do you recall any memorable films that you caught at Eros Cinema?

It’s hard to recall specific films I saw at Eros, but I do remember the experience clearly. During the interval, we always had a chicken mayo roll, a bag of wafers, or a choco bar. There was no popcorn back then. I also remember a little café in Colaba called Paradise, run by a Parsi family, which served excellent chicken rice and hot dogs. They supplied food to most theatres, including Excelsior, which I frequented while studying at Cathedral School, walking there just for their chicken rolls. Eros was lovely and even had a preview theatre.

Do you have a favourite Kamdar piece? Any project that is your favourite?

There were so many. We did a lot of work for the Mafatlals, and the Bhagat residence was particularly beautiful. The Taj Harbour Bar was very special to me. I was most upset when part of it was demolished. It was a beautiful space with copper plate detailing, and what made it even more exciting was the fresco on the wall, done by Messerschmidt himself. It featured Rajasthani figures, daggers, swords and the entire composition came together in such a stunning way.

I believe it was one of the most delightful pieces of work we were involved in. Rendezvous, of course. Our own home [at Seaface Park, Cumbala Hill] also holds special memories. Messerschmidt had painted a mural on a hardboard there. In the dining room, everything was done in rosewood. The table rose from the floor, and behind it were planters with concealed lighting. Messerschmidt painted the entire Pratapgad Fort on the wall. The warm yellow light made it look like a sunset, and other tube lights around it created a glowing sky effect.

Seaface Park is a very iconic Art Deco complex in itself, designed by Master, Sathe & Bhuta. What are your memories of growing up there, what was around there?

It was incredibly forward-thinking for its time. The building had an in-house swimming pool, a rare feature back then. Even more unusual was that it had a dedicated garden for dogs, a children’s garden, and a large main lawn. The most remarkable thing, especially compared to other buildings of that era, even those on Marine Drive, was that there were 60 flats and 60 garages. Each apartment had its own parking. Contrast that with places like Cuffe Parade today, where there’s barely any parking. That kind of planning was unheard of back then.

Mafatlal Park was actually built on reclaimed land. Anand Bhavan [originally built as a residence for Maharaja Indrasinhji Pratapsinhji of former princely state of Bansda, Gujarat, and designed by Master Sathe and Bhuta] was nearby. Opposite us was a Parsi bungalow, where the Benzer store is today. Back then, what is now known as Bhulabhai Desai Road was called Warden Road. We used to walk from there to Pedder Road through what was then a jungle. We’d chase rabbits and watch beautiful sunrises. Of course, a lot has changed since then, Bombay has undergone some unfortunate transformations. I think with the awakening and knowledge, the government should also help. They should be proud of what is here.

This blog is based on an interview with Mr Vikram Kamdar conducted by Suhasini Krishnan and Theertha Gangadharan of Art Deco Mumbai Trust on 29 November 2023 and edited by Vandita Shukla. Header Image: Digital illustration by Vandita Shukla for Art Deco Mumbai Trust.