“The democratic spirit of Shivaji Park arises out of the presence of the expansive park where everybody finds something recreational to do”

In February this year, journalist, cultural critic and author Shanta Gokhale launched Shivaji Park – Dadar 28: History, Places, People. The multilingual writer and translator, noted for her Marathi novel Rita Welinkar, who has been associated with publications such as The Times of India, Mumbai Mirror, Scroll.in and the now-defunct The Independent, has penned this monograph on the neighbourhood she calls home.

In this book, she sidesteps nostalgia and delves into the history and culture of Shivaji Park while building a portrait of what is one of Mumbai’s earliest planned neighbourhoods and an underrated Art Deco district. In this interview done with Art Deco Mumbai over email, Gokhale speaks about the role of Shivaji Park’s cultural institutions, politics and architecture in the lives of its residents and how they came together to shape its unique culture. Excerpts:

How long have you lived in this neighbourhood and what was the genesis of your book, ‘Shivaji Park – Dadar 28: History, Places, People’?

We moved into this flat when I was one year old. I have lived here all my life other than the six years I spent abroad and nine years away after marriage. That makes 65 years of my 81-year-old life spent in Shivaji Park.

Jerry Pinto introduced me to Ravi Singh of Speaking Tiger. Ravi had planned a series of monographs on neighbourhoods. He had already published two on parts of Delhi and proposed I do one on Shivaji Park. The word limit was 35,000.

What are the aspects — spatial, architectural, political, etc — that make Shivaji Park a ‘democratic’ space?

I would not claim that the democratic spirit of Shivaji Park arises out of its architecture, space or politics. It arises entirely and solely out of the presence of the expansive park where everybody finds something recreational to do, which adds significantly to their individual lives. It has no notice boards forbidding anyone entry.

There is no intimidating fencing except around Balasaheb Thackeray’s memorial and Shivaji’s statue. It is a free and open space

What has been the contribution of the ‘katta’, or the Park’s boundary wall, to the neighbourhood?

The katta is a hangout for children, youth and the superannuated. It is a place where one can laugh in company or meditate alone. A certain breezy lingo has grown around it and is named after it. The katta has also lent its name to fora used for informal discussions. In this case, the place came first, the social habit afterwards.

For all we know, it was built only to mark the boundary of the park. Its height, which makes it perfect for sitting and sleeping, was quite possibly the result of the available budget. Anything higher would have meant more money. As far as Shivaji Park residents are concerned, however, anything higher would have destroyed the katta‘s enormous contribution to their social life.

The katta is a hangout for children, youth and the superannuated. It is a place where one can laugh in company or meditate alone. A certain breezy lingo has grown around it and is named after it. The katta has also lent its name to fora used for informal discussions.

What distinguishes Shivaji Park from other public spaces, such as Oval Maidan? Why does Oval Maidan have a perception of being “snooty”, as stated in the book, despite being as much a public space as Shivaji Park?

Each public space has its own character as does the Oval. The perception that the Oval is snooty belongs in my book to architect Mustansir Dalvi. I am not aware that it is shared by the common public. To my mind, the contrast between the two comes from the surrounding buildings. The row of art deco buildings that face the Oval look as though they have come out of the same mould, giving the area an elegant but rigid appearance. The buildings around Shivaji Park are highly individualistic, lending it a strong appearance of a free and easy space.

There are several clubs and organisations in Shivaji Park. Are there factors that make this neighbourhood predisposed to such collectives?

That is difficult to answer. Human life in the modern age is fluid. There cannot be a hard and fast reason to explain any of its phenomena. The people who moved to Shivaji Park from the congested parts of the city must have felt they were free here to make their own lives because everything was being made anew. Clearly, a spirit of social enterprise must have driven them to create clubs and organisations that catered to their interests. I can only say that getting together around a common interest is what marks modern societies. The Dadar Sarvajanik Vachanalaya is a case in point. A handful of voracious readers got together and set up a library because they realised many in this new neighbourhood would be happy to access books at an affordable fee.

The various institutions and the open space give Shivaji Park its “sense of a place”. Was this planned from the beginning, or was it an organic process? Why has it declined over the years?

The “sense of a place” is intangible. It cannot be planned. The park itself contributes greatly to it although it was planned only as an open space where people could relax, play and enjoy the healthy sea breeze. It is always people who make a place. What they wear, how they celebrate festivals, how they haggle with vendors, how they call out to friends from the street — all these create this “sense”. Verandahs, a common feature in every flat, make calling out to friends from the street possible. The new towers are too tall for this and lack spacious verandahs. The newcomers do not ‘belong’ together as the old residents did, many of whom had a common past in south Bombay. They had inhabited similar chawls and therefore lived similar lives. So they were almost a readymade community when they arrived in the new neighbourhood. Not so the new residents who come from everywhere. “I’ve seen you around Shivaji Park,” is a line one still hears exchanged between the older residents. They meet in the park, in the temples, in the theatres for afternoon shows of plays, at people’s homes for private mehfils. Do the new residents share these interests? It’s difficult to tell because we do not recognise their faces.

“I’ve seen you around Shivaji Park,” is a line one still hears exchanged between the older residents.

In your book, you say: ‘Flats at Shivaji Park were tools for cultural engineering’. Was the advent of the ‘modern’ household differently received in the houses–and communities–of Shivaji Park as compared to other parts of the city?

I have no means of comparison with other places in Bombay nor would I say there was any aspect of modern living that was unique to Shivaji Park. But Shivaji Park, along with Matunga and Five Gardens–neighbourhoods that were developed around the same time as Shivaji Park– were all part of the trend towards a form of modern living as reflected in its apartment houses.

Shivaji Park introduced apartment-style living to the city. Why was there a disdain for this style over the chawl system, and when did it decline?

Chawls fulfilled the residents’ urge for a community life. After uprooting themselves from various regions in the interiors of Maharashtra for an enormous and communally heterogeneous (cosmopolitan) city, it was comforting to live cheek-by-jowl with your kind of people. Chawls were cheaper to build and live in, and could be used for a greater density of occupation than apartments.

Community versus the individual is one axis of the movement from tradition to modernity that the city was experiencing in the early decades of the 20th century. The split was represented as much in social life as in political and cultural life. In politics, Bal Gangadhar Tilak represented nativism — we are fine the way we are — and Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Justice Ranade and others represented reformism. The former were called jahal and the latter maval — hawks and doves. In cultural life, the issues provided material for the most significant plays written and staged in the first three decades of the century. The plays written by reactionaries have been lost to time. Those written by progressives have outlived their time as classics.

Chawls represented community life and therefore appealed to conservative sentiments. That is why some people did not want to move into apartments. Apartments represented modernity, that is ‘individual above community’. Hence the disdain by conservatives of apartments, that is, of modernity.

Was there a difference in apartment structure and lifestyle amongst the different communities?

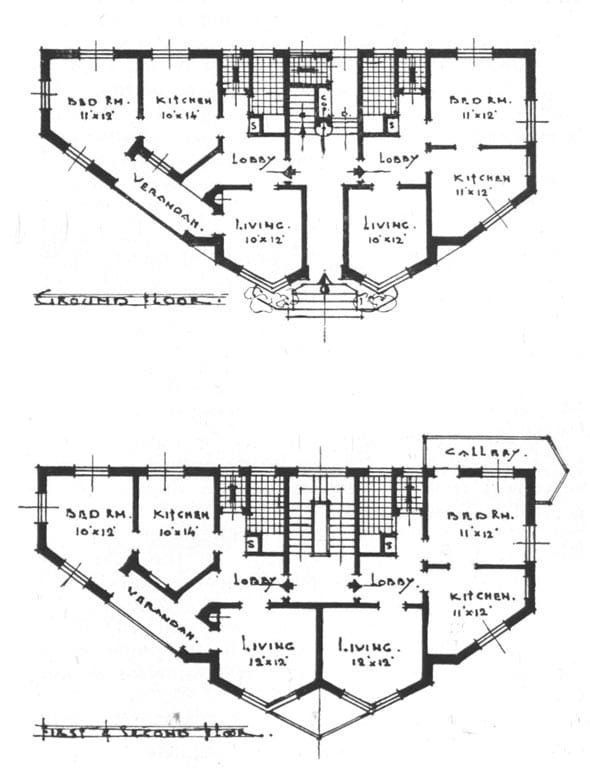

I doubt it. Houses were not built for specific communities. They all had a living room, a kitchen-cum-dining room, a bedroom or two, and a single toilet and bathroom to be shared by the whole family. The location of the toilets was critical. I have explained this at length in my book. By and large, this design decided how people lived. There were of course certain aspects of lifestyle which could be adopted to the available spaces. The most obvious example was Shivaji Park’s Gujaratis hanging large swings in their living rooms.

In your book, you say, “The unique culture of Shivaji Park arose from its institutions and its people”. How did Shivaji Park become the region where diverse fields, such as sports, music, theatre, developed, excelled and co-existed? How much did institutions, such as the various performance halls and sports clubs, contribute to this culture?

Nothing in human life happens suddenly. I must give you the historical background to the place of theatre and music in the life of Maharashtra in order to show you why institutions couldn’t have made the culture of Shivaji Park.

Let us first consider theatre. In 1843, the Raja of Sangli asked one of his young courtiers, Vishnudas Bhave, to create a performance that would entertain and edify the courtiers. Bhave’s Sita Swayamvar, written and designed by him and staged with a ragtag bunch of lowly brahmins, is recorded as the first Marathi play. Thereafter, this form of musical entertainment took off and became a forte of Maharashtra. Bombay, the country’s commercial centre, allowed Bhave and his followers to put theatre on a firm footing as an industry. While they served Maharashtrians in the city and region, Parsi theatre did the same for the Gujaratis and Bhatias. The British, with their long tradition of theatre, were a great influence on both. Marathi and Parsi plays were performed in the old indoor theatres built for the troupes that travelled from England to the Colonies to entertain the British population. Gradually, Marathi theatre became a cultural tradition.

After Independence, the Mumbai Marathi Sahitya Sangh (MMSS) at Charni Road became the centre of Marathi theatre. Built in 1963, theirs was the first indoor theatre in Bombay dedicated to Marathi plays. When the demographic shift began as middle and lower middle class Maharashtrians began to move out of Girgaon and its surroundings into the northern suburbs, the MMSS slowly became a shadow of its former self. Meanwhile, auditoria were mushrooming in the suburbs, take for example Ravindra Natya Mandir in Prabhadevi and Shivaji Mandir in Shivaji Park. So did institutions contribute to shaping the culture? I would say institutions are built for people because people want them; the need comes first and the supply follows.

When the demographic shift began as middle and lower middle class Maharashtrians began to move out of Girgaon and its surroundings into the northern suburbs, the MMSS slowly became a shadow of its former self. Meanwhile, auditoria were mushrooming in the suburbs, take for example Ravindra Natya Mandir in Prabhadevi and Shivaji Mandir in Shivaji Park.

I will turn to music now. In 1880, when the Peshwas ceded the Maratha Empire to the British, Marathi upper castes–the royalty and nobility–lost their identity and purpose in life. A few brahmins decided to go north to learn the new gayaki khayal, which had supplanted dhrupad in the courts of rajas, the chief patrons of classical music. Some of them returned to Maharashtra and found employment in the well-established sangit natak theatre tradition. They became music composers and introduced raga-based songs in plays, replacing the old folk melodies. This made natya sangit extremely popular and was indirectly responsible for the love Maharashtrians have for classical music. As Maharashtrians migrated away from Girgaum and its neighbouring localities, venues for classical music like Trinity Club, Laxmi Baug and Brahman Sabha, lost their purpose. Several similar institutions instead flourished in Shivaji Park, of which Dadar-Matunga Cultural Centre is the oldest and most active.

The story of sports is different. The British influenced the locals into believing that games are good for human health, which led to the popularity of cricket, badminton and tennis. Hence, badminton and tennis courts were built for the residents of Shivaji Park as well as an Olympic size swimming pool. At the same time, ideas of nationalism had taken root. So institutions like the Shree Samarth Vyayam Mandir in Shivaji Park came up where the focus, along with western style gymnastics, was on activities like kho-kho, surya namaskars and mallakhamb. The latter developed into an international form of gymnastics.

As Maharashtrians migrated away from Girgaum and its neighbouring localities, venues for classical music like Trinity Club, Laxmi Baug and Brahman Sabha, lost their purpose. Several similar institutions instead flourished in Shivaji Park, of which Dadar-Matunga Cultural Centre is the oldest and most active.

Did the food culture at Shivaji Park — its restaurants, street food inventions or specialties — in any way change the culinary map of Mumbai?

I believe Dadar chowpatty ranked a little below Juhu and Girgaum chowpatty for bhelpuri and other chaat items. People from Worli to Bandra and from Hindu Colony and Parsi Colony would come to the beach both for its chaat and the air. Unfortunately, several factors gradually robbed the beach of its sand and so of the majority of its chaat carts. So that part of Shivaji Park’s food culture faded away. But there were other things happening at the park, which had gradually become a hangout for young people from the same areas — Worli to Bandra and Dadar East. Here, a new form of street food was introduced in the early 1980s — the frankie. There was one other frankie stall in Dadar, at the corner of a street leading to the railway station. The young hung around the stalls, the older people quietly took it home. Sindhudurg was the first restaurant that SoBo people flocked to for Malwani seafood before the famous two in Fort made their appearance. After Girgaum, non-Marathis began to congregate at Aswad restaurant, opposite Shiv Sena Bhavan, for their thalipith, pohe and puran poli. I should not forget to mention Gypsy Corner, our first pavement cafe which combined Aswad, Dadar Chowpatty and Madras Cafe in its menu. Gypsy Chinese equalled Worli’s Flora in its widespread appeal. Both places, owned by the same family, certainly changed the eating habits of middle-class Shivaji Park and surroundings, for some time even supplanting the attractions of Dadar East’s Pritam.

The Bimb dynasty is supposed to have caused the most changes in the socio-political landscape of the Dadar/Shivaji Park area. When did the Marathi-speaking community rise to prominence? Also, in the book you speak of reputed or respectable middle-class families, several prominent personalities who called this neighbourhood home. What led to so many such people inhabiting Shivaji Park?

My book answers a large part of the question. There is no question of anybody rising to prominence. There was a great social and political churning after Independence. We had to forge a new identity for ourselves. Movements were born to help build the nation. Shivaji Park played its part because, unlike the middle-class of today that is flush with money and has disposable incomes but little disposable time, the old middle class had to be thrifty, took pride in its culture and had time for its neighbours. Everybody was in it together. If I have mentioned certain personalities in my book, it is because Maharashtra led the way for a while in cricket, politics, music and theatre. That could happen anywhere, anytime.

When did Dadar and Shivaji Park become a hotbed of Marathi identity and politics? How much did the activities of revolutionaries such as VD Savarkar and Mahadev Bapat contribute to the political identity of Shivaji Park?

The primary cause was the birth of the Shiv Sena. Their journey is well-documented so I don’t need to go into it here. Senapati Bapat is hardly spoken of now. But Savarkar is. He always had a huge following, not in Shivaji Park in particular although he lived here, but all over Maharashtra. His ideas influenced national rather than local politics. The current Prime Minister holds him in high esteem.

How strongly are the people advocating for the conservation of the buildings (especially the Art Deco structures) and the Park as a heritage zone?

An independent scholar who was investigating this question with regards to Marine Drive, found the residents were very concerned about its heritage status. Shivaji Park residents do not belong to the well-to-do business communities that live along Marine Drive. They are professionals and clerks with limited salaries. For them, the money that a developer will give, along with a brand new apartment, is more precious than heritage. Heritage is seen as architectural splendour. The old colonial edifices in South Bombay are heritage. How can the ‘ordinary’ buildings in which ‘ordinary’ people live, be heritage? As Raj Thackeray said, only the Mayor’s bungalow is worth saving in Shivaji Park.

For them, the money that a developer will give, along with a brand new apartment, is more precious than heritage.

SN Pendse talks about the different ‘skins’ or phases of Dadar. What do you think Shivaji Park will look like in its next phase, and what will be the future of its unique culture and heritage?

We already know what Shivaji park will look like. Some landlords are trying hard to preserve their buildings against development. But most are submitting to development. As I have said in my book, in the old days, if you looked across Shivaji Park, you saw trees. Now you see towers. The skyline was once more or less uniform. Now it is already jagged with sudden ups and sudden downs. There will soon be only towers. Those might in time become heritage. Who knows?