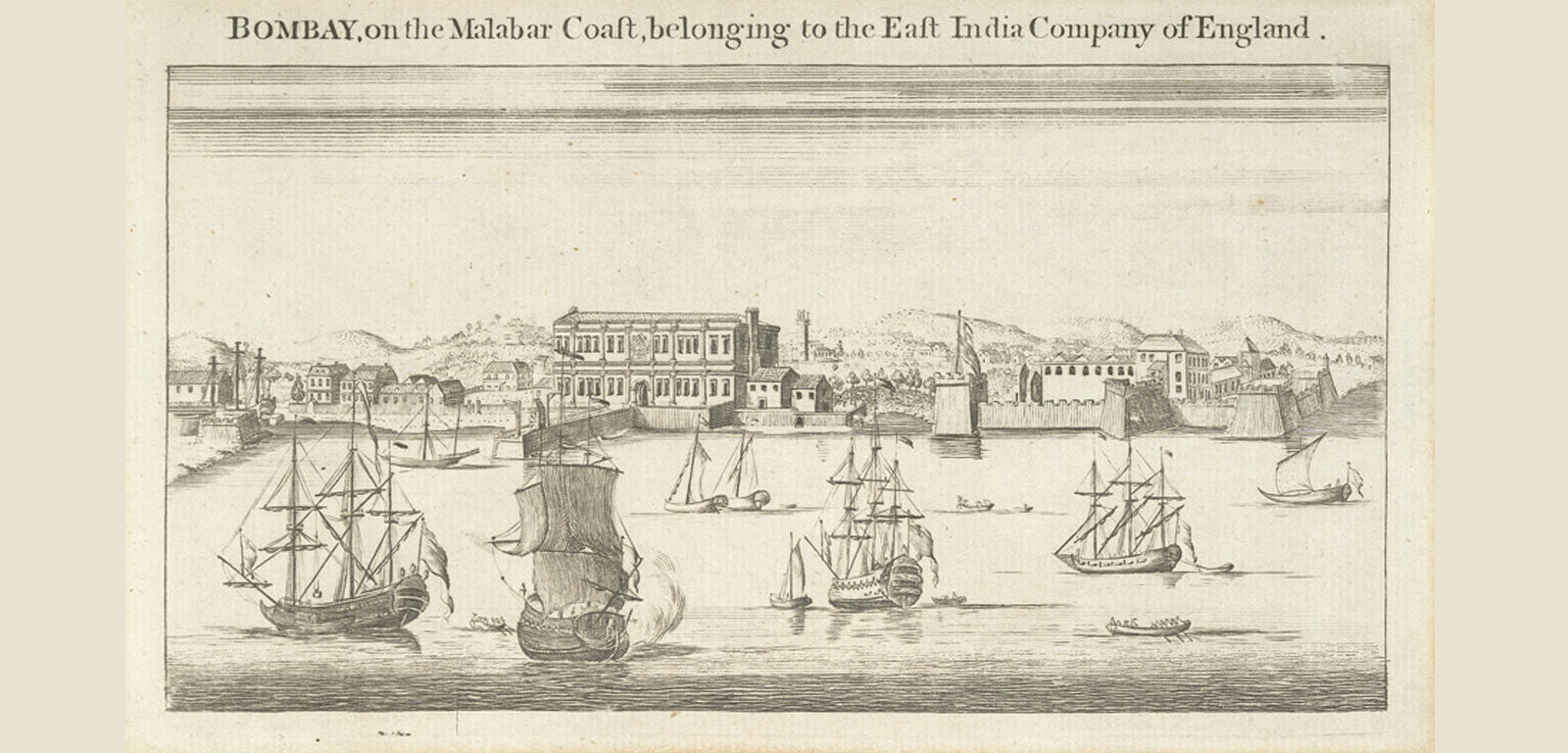

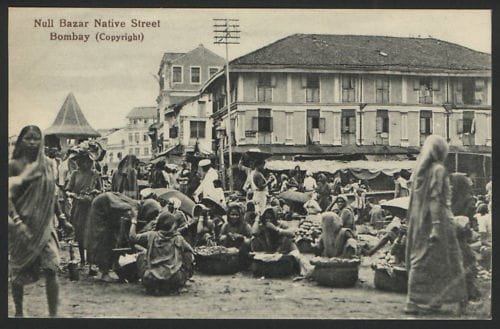

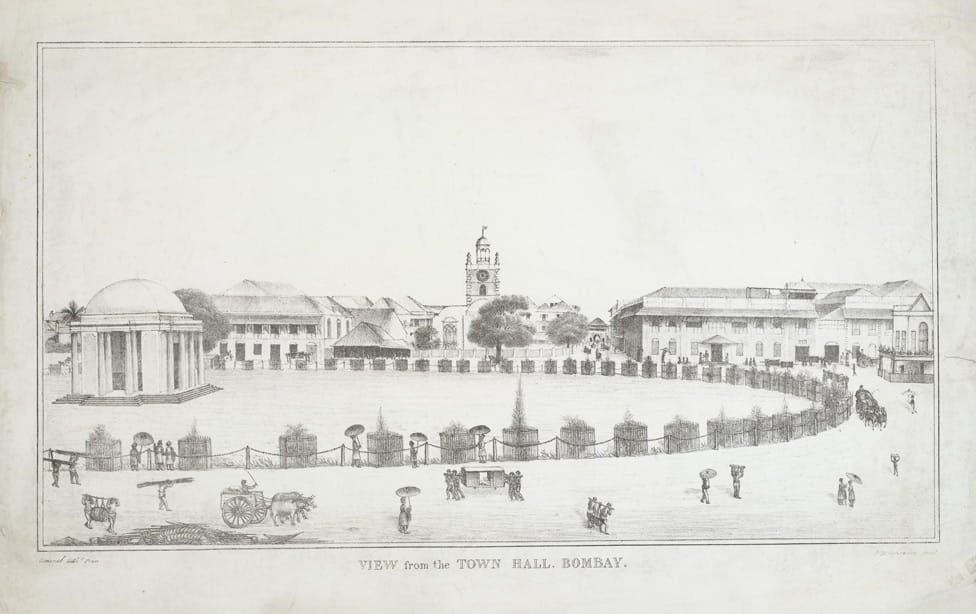

The urban development of Bombay as a capitalist port city, was a result of the distinct location of the western Indian Colony. Sociologically, the early Victorian Bombay emerged as a capitalist city with class differentiation determining the spatial pattern of the city. The colonial / indigenous spatial dualism was just an outcome of this urban sociological pattern. The early 19th century Bombay was fast acquiring an easily recognizable capitalist face.

The city was well maintained in parts, it was squalid and congested in others. Population was expanding; there was growing functional specialization and division of labour; relations of the market were penetrating day to day life; and class differentiation was cruelly apparent. Urban development in the 19th century Bombay has to be placed within the wider framework of the development of capitalism and the intervention of colonialism. It goes without saying that colonial rulers brought to urban development in India certain features which were inherited from the historical evolution of cities in the metropolis. (i) At the same time, it has to be borne in mind that such features were inescapable in so far as colonial rule drew various urban centres in India into a network of capitalist relations. Indian cities on which the British left their imprint became less or more capitalist cities depending upon the extent to which capitalism was able to develop/ not develop in them or in the region/s in which they were located. (ii)

ACCOMMODATING DEMAND

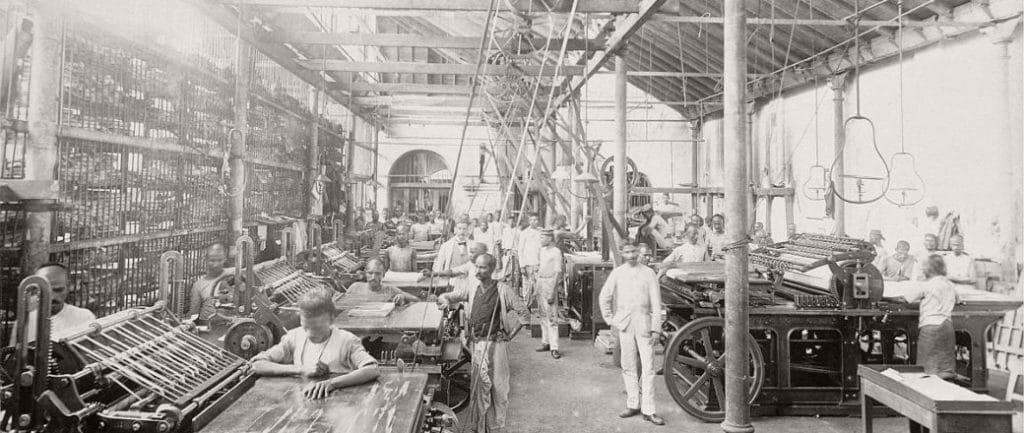

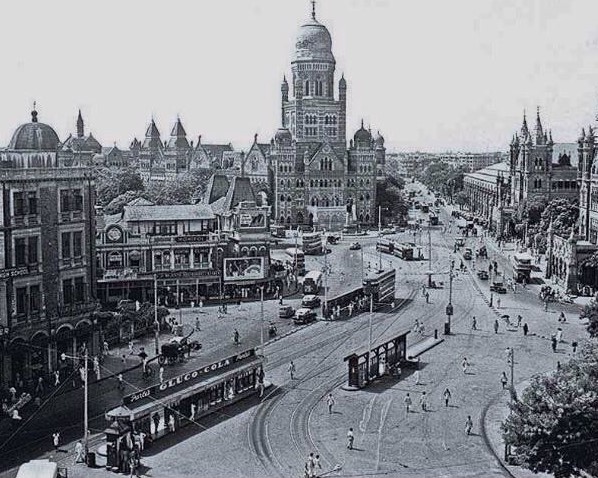

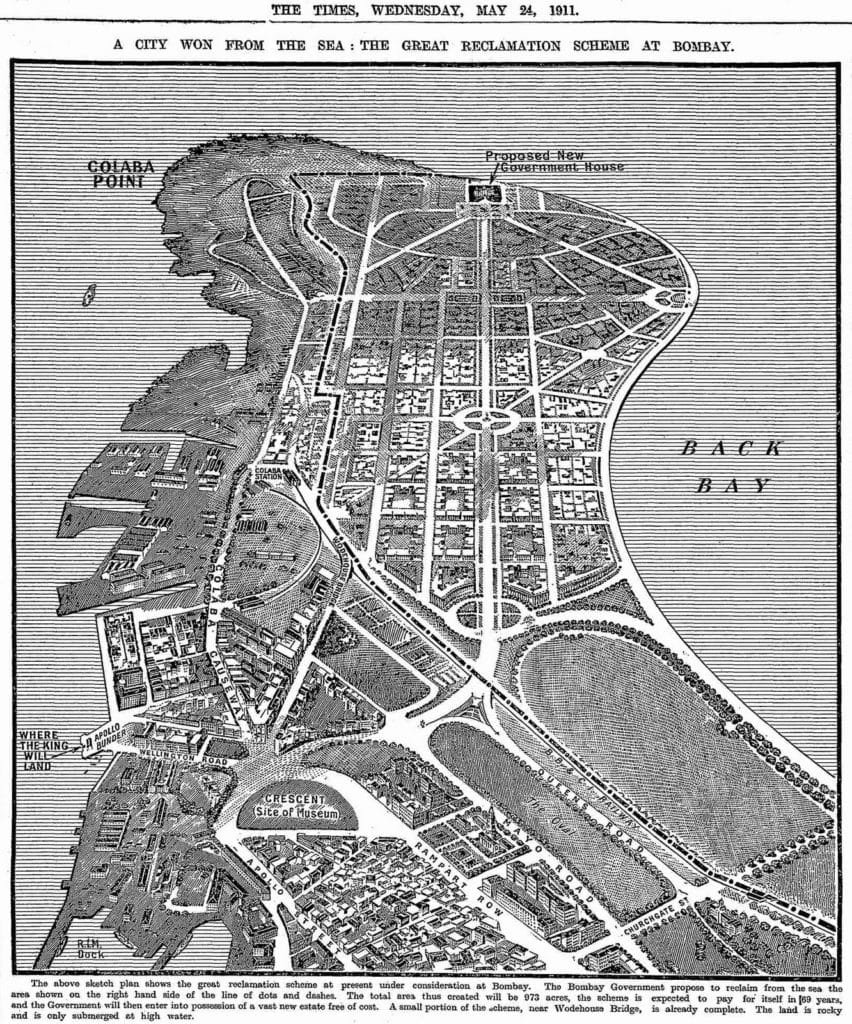

The last two decades of the 19th century, starting from 1880, saw a wave of immigrants coming to Bombay, that considerably altered the character of the city. By the beginning of the 20th century, not only did the city’s physical form change, but also the social and cultural patterns and its political framework also changed. The decades that followed saw a lot of planned interventions by the Government as well as private enterprise. The influx of people was used to the city’s advantage, in terms of its industrial and commercial base. The urban form of Bombay thus underwent significant transformations as a result of rapid industrialization coupled with massive reclamations, road and housing projects. Most of these projects were implemented by the Improvement Trust and the Port Trust which together added considerable land to house the new components of the population. (iii)

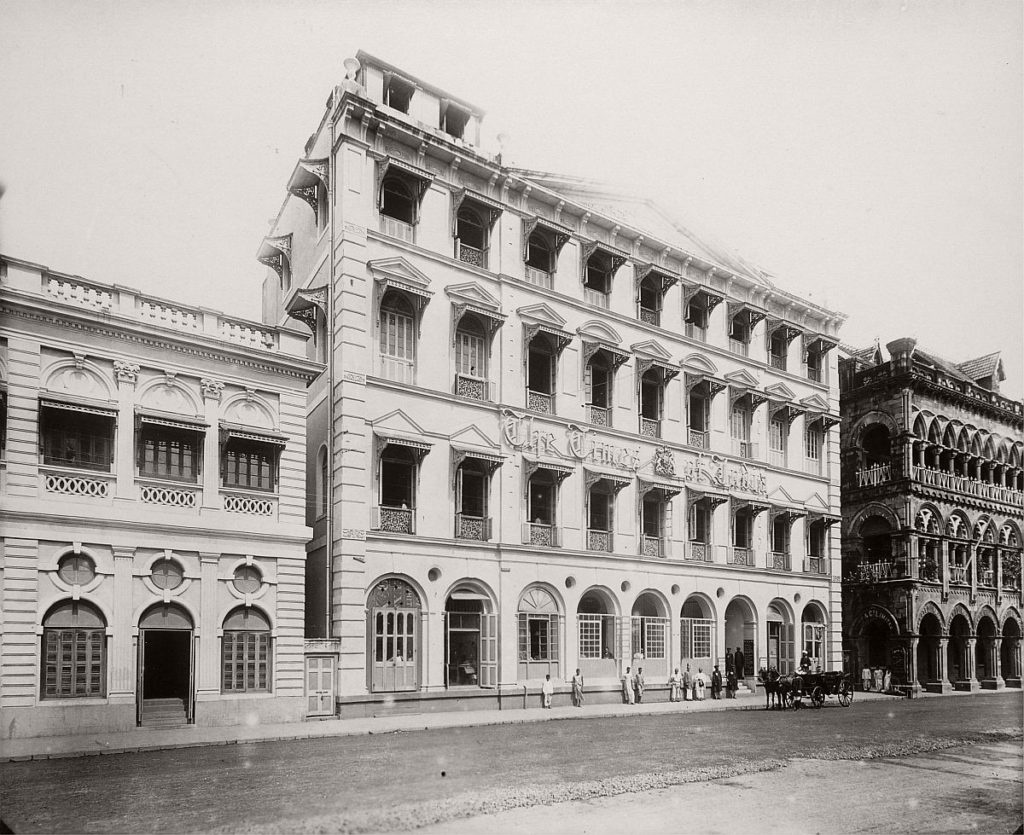

Bombay’s business and industrial expansion resulted in several noteworthy commercial associations, which led to demand for commercial space as well as additional workers’ housing. The commercial demand being highest in the core of the Fort Area, there were implications on the Urban Planning of the city. With roads being widened by the Municipality in the southern section, setbacks and realignments were laid down and extensive reconstruction was taking place.

Bombay was fortunate in its rich natural resources of sand and trap stone which was ideal for concrete aggregate. (iv) The advent of RCC in the early 1900s proved to be a boon in disguise providing a changeover to a high- rise building typology for the high-density situation prevalent in Bombay.

SHIFT IN ARCHITECTURAL STYLES

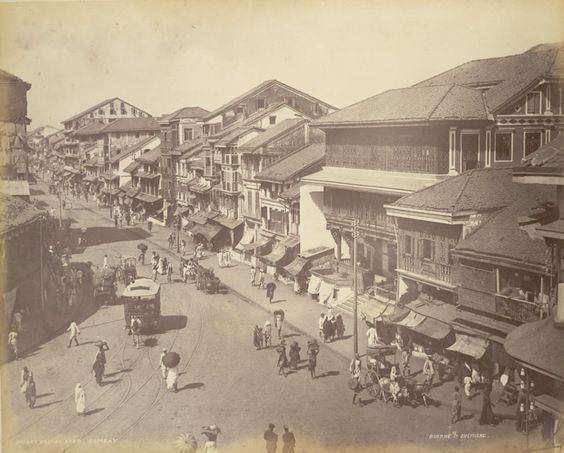

The evolution of Bombay as a city is evident from how the British manipulated its abundant resources to their benefit. From the Seven Islands to Bombay as a trading town, gradually transforming into a fledging industrial and manufacturing center, Bombay’s metamorphosis was aided and accelerated by economic, political and physical changes. Much of these changes in the Urban Morphology were outcomes of historic events that took place in and around the city. To name some, the annexure of Deccan by the British in 1819, linking Bombay to the Deccan and Konkan regions by road in 1830 and then by rail in 1863, the construction of the Mahim- Bandra causeway in 1845 providing easier access from Bombay to the hinterland. The establishment of an overland route to London in 1838 and the opening of Suez Canal in 1869, created global channels for movement of goods and people.

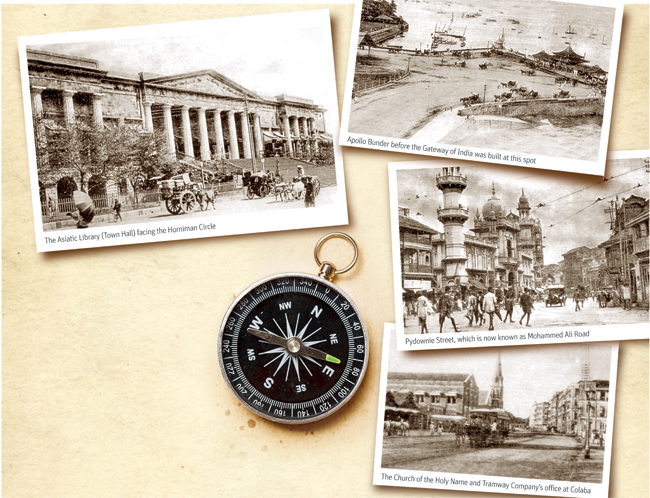

In the 1850s and 60s, Bombay’s progress was significantly due to the acumen of John Lord Elphinstone and Sir Bartle Frere. This was the time when initiatives by Lord Elphinstone, Governor of Bombay (1853-1860), the Fort Improvement committee was established, perceiving the futility of the town bastions, took efforts to remove the fortification to the advantage of the town’s growth. However, it was only during the reign of Sir Bartle Frere, the Governor of Bombay (1862-1867), who took a momentous and prudent decision to demolish the unnecessary fort walls and restructure the town.

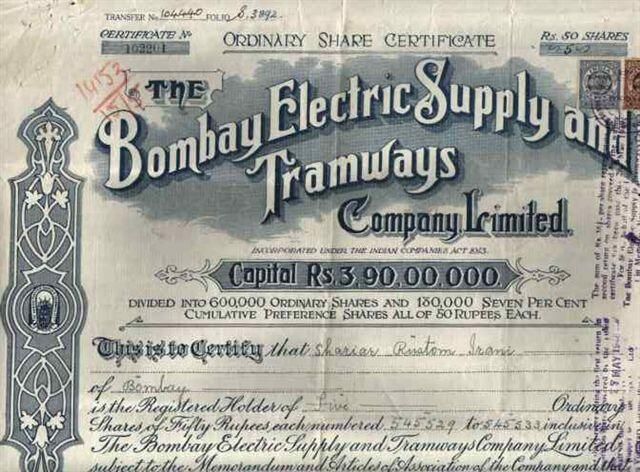

Bombay was no longer perceived as merely a fortified trading town by the Crown. It became a pivotal Presidency capital that symbolised colonial power and as a crucial connection between India and the globe. The American Civil war, right after the reign of Lord Elphinstone as the Governor, resulted in a boom in cotton trade. The inability of America to provide cotton and the abundantly available raw cotton in western and central India forced purchase of cotton from the Bombay markets. This resulted not just in a commercial boom with Bombay receiving £81 million but also speculation in equity shares of companies that were to undertake extravagant reclamation schemes.

Architecturally, Gothic building style was manifested the most, for its imposing grandeur, serves as a testament to the power of trade, of shared printed design resources and the discovery that architects as well as component building parts could be exported to India. It also informs the city’s interaction with the architectural fashions of the world stage. (v) This later evolved into Gothic Revival architecture, Architect F. W. Stevens being referred to as the great Bombay Gothic Revival architect. Most major buildings commissioned during the late 1800s were designed and constructed by him.

A shift from the Gothic style to the Indo- Saracenic was indeed a big shift for Bombay. The style evolved as a result of the Jeypore Portfolio of Architectural Details produced by Swinton Jacob. It consisted of 6 volumes of 600 large scale drawings of elements picked from various buildings dating between the 12th and the 17th centuries. What was especially important was that the work was not organised by period or region but by function- coping and plinths in one volume, arches in the second, brackets in the third and so on. These were presented as loose sheets in order that different examples of details might be compared and selections readily and easily made. It was through the works of British architects like R F Chisolm, John Begg and George Wittet that this style found its way to Bombay.

There was much apprehension from the Government and bureaucratic opposition for this shift in styles. This can be best captured in the following statement made in an address to the Royal Institute of British Architects by James Ransome, the first consulting architect to the Government of India, in 1902.(vi)

“In India, where ingenuity was required more than anything, we were forcing purity of style. I was told to make Calcutta Classical, Bombay Gothic, Madras Saracenic, Rangoon was to be Renaissance and English cottages were to be dotted about all over the plains of India.” – James Ransome, address to the RIBA

The early years of the 20th century saw the climax of Gothic Architecture in Bombay. The Edwardian, the Renaissance and the Indo- Saracenic styles of architecture dotted the skyline of the 1900s Bombay. This was an effort to achieve the Colony’s adaptability to the Indian conditions.

TRANSITIONS TO MODERNITY

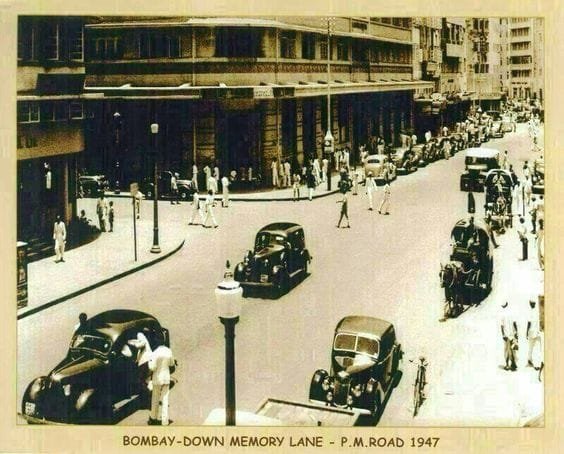

The Great War, also known as the First World War, was a global war that lasted from July 1914 to November 1919. Bombay in the interwar year was a city in transition. It was during this time that the city’s urban fabric witnessed a shift from the colonial, Victorian city to a moderne metropolis. Some radical transformations took place in Bombay from 1919, the closing year of the World War I. The Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes, an exhibition held at Paris in 1925, became the harbinger of a new movement in architecture and the decorative arts that came to be termed as Art Deco. (vii)

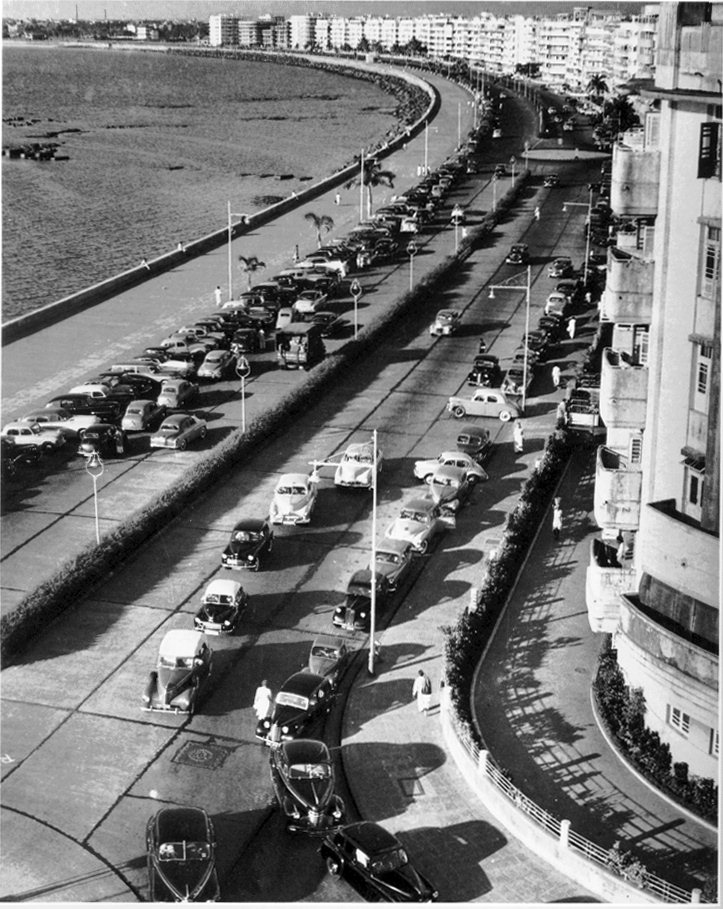

In Bombay, new patterns of lifestyle became evident during this period, with the introduction of concepts such as ‘commuting’ to the place of work or travelling distances for a weekend outing. Concepts of family entertainment such as Cinema and social clubs, encouraged mixed gatherings and the socializing of women- a custom that was frowned upto by the local Bombay society. This led to Bombay becoming a trend setter in social reform.

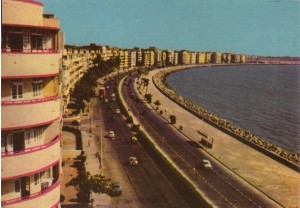

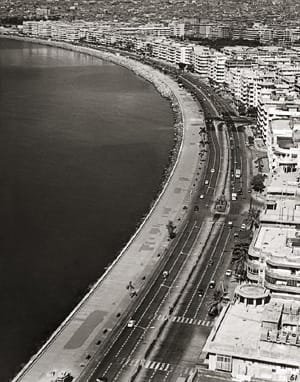

The Art Deco style first appeared in India when Indian royal families and entrepreneurs and merchants of the widely travelled educated upper middle class, eager to adopt contemporary trends in western culture, began to assume sophistication in dress, furnishings and architectural design. In the 1930s Bombay saw its educated middle class grow as a result of the city’s expanding port commerce. The pressing requirement of housing resulted in large scale reclamation projects such as the Back-Bay Reclamation Scheme, initiated and implemented from 1928 to 1942. The new city’s spurring building activity and the need for a new architectural style expressing the requisite optimism, Art Deco style became a sorted- to style of Architecture.

“French in origin, the Art Deco style represents the world’s first initial amalgamation of modern design movements. The style synthesised a number of dynamic influences that culminated in an exclusive fashion of high taste in Europe- primarily Paris during the first two decades of the 20th century. These included forces as disparate as the German Bauhaus, the Ballets Russes, Oriental and African Art, Egyptian, Aztec, Mayan and early Greek architecture, aerodynamism, zigzag geometry, moderne stream lining and visual expression of jazz music. Concurrently the Italian futurists and the French and the Spanish Cubists were graphically changing established perceptions of time and dimension while Hollywood was thrusting its signature glamour across the world’s movie screens. Expanded communications in the forms of radio, telephone and magazines along with broadened travel via the automobile, ocean- liner, locomotive, and airplane facilitated the spread in the awareness of Art Deco’s thrilling combination of romance, sophistication, rhythm and geometry.” (viii)

This was also the time when Bombay was undergoing advancements of capitalist urbanism. A unique combination of factors led to the popular adaption of Art Deco in Bombay. Tourism and travel had made rapid strides in the period between the two World Wars, resulting in a continuing stream of visitors to Bombay. The social and cultural ambience at Bombay was thus suitably conducive to the introduction of Art Deco architecture and interiors. The upper class and the business community of entrepreneurs and managers happily imbibed contemporary trends in western culture to create a bon vivant lifestyle, that symbolized gaiety and colour and encompassed western cuisine, dress, ballroom dancing, jazz, cabarets, horse- racing and the cinema. (ix)

A steady shift in the design culture and its relationship with the political economy of Bombay is seen through the passage of time and the emergence of Art Deco Architecture in Bombay has been very important in the city’s developmental history under the aspects of Urban Morphology and Architecture. Many Indians who were businessmen (predominantly Parsis) travelling to Europe had to spend several weeks to reach London (before the Suez Canal was accessible) and it was around the same period that Hollywood’s fame was heard throughout the length and breadth of Europe, impacted the business class of India. These people actively contributed to the skyline of Bombay and making buildings that were more ‘Indian’ in nature as compared to the Colonial Victorian Gothic, Neo- Classical, Renaissance, etc. that were more ‘English’ in nature.

Many Indian architects and contracting companies such as Sohrabji Bhedwar, G. B. Mhatre, Merwanji Bana & Co., Shapoorji Pallonji & Co. contributed to the growth of the Art Deco style of Architecture. Many eminent buildings starting with Regal cinema (1933), Dhanraj Mahal (1935-38), were all built by the Gregson, Batley and King Co. contracted by eminent Parsi contractors, whereas the native residential complexes along the Oval Maidan and Marine Drive, were dealt with by prominent Indian architects such as G. B. Mhatre. Indian architects and designers also contributed imposing structures to the City such as the New India Assurance building (1936)- designed by Master, Sathe and Bhuta, with artistic designer N. G. Pansare, the Eros Cinemas designed and built by Architect Sohrabji Bhedwar.

This turned out to demonstrate a collective language that creates an urban fabric while individually allowing creative expression, each competing with the other in flamboyance and sophistication. With the first generation of Indian Architects from the Bombay School of Art, contributing avidly to the city’s skyline through the new-found style of Art and Architectural expression- Art Deco, it has proved to be a manifestation of the works of Indian Architects over the dominating works of colonialism and imperialism.

Prathyaksha Krishna Prasad for Art Deco Mumbai

Prathyaksha is an urban conservation architect & researcher. She has two Master’s degrees, one in Urban Conservation and the other in History and Heritage Management. Her research work includes the incorporation of Heritage Driven Urban Regeneration for Indian Cities and Rural Heritage tourism management for Champaner – Pavagadh Archaeological Park. She has also worked as a research intern, under Ar. Rahul Mehrotra for the Harvard Graduate School of Design Program titled “Extreme Urbanism IV- Looking at Hyper Density- Dongri, Mumbai”.