This article has been reproduced with permission from the Art Deco Society of New York. It originally appeared in the Winter 2018 issue of the Journal of The Art Deco Society of New York.

A New World Heritage Site

On June 30, 2018, following a decade-long effort, UNESCO inscribed The Victorian Gothic and Art Deco Ensembles of Mumbai as a World Heritage Site. This inscription serves to protect, enhance and showcase a spectacular ensemble of 94 historic buildings, which includes the unrivaled Art Deco promenade of Marine Drive.

The journey towards World Heritage status was unique simply because no World Heritage Site nomination had previously been initiated by stakeholders. Typically, the initiative, impetus, funding and preparation of the dossier are driven by the state government. In the case of Mumbai (formerly Bombay until 1995 when it was renamed, but often referred to as Bombay when recounting its history), the entire nomination dossier, running over 1,500 pages, was completed by a group of individual citizens, resident associations, architects, conservationists and urban planners, led by Abha Narain Lambah & Associates, a prominent Indian architectural conservation firm. Politicians worked across ideologies and party lines to support the initiative.

Two centuries, the nineteenth and twentieth, straddle the Oval Maidan, or public park, making the area unparalleled. The dramatic confrontation of the two styles across the Oval reflects two waves of urban expansion and two major styles: Victorian Neo-Gothic and Art Deco. Other styles are also represented, including Indo-Saracenic and Neoclassical, but the Art Deco buildings are particularly impressive – together they form one of the largest and most homogeneous such assemblages in Asia and the world, with the spectacular coastal promenade, Marine Drive, sweeping the western boundary of the precinct. This formidable architectural ensemble influenced the development of Modernism in Asia with a distinct architectural genre – western in form and Indian in spirit – as an example of shared heritage.

First City of India

In 1661, before gifting the islands of Bombay to King Charles II of England as a dowry for marrying Princess Catherine of Braganza, the Portuguese controlled the seven islands of Bombay, then called Bom Bahia, with the aim of proselytizing the natives and using the islands as a port for their spice trade.

It was only after 1668, when the British Crown handed over the islands to the East India Company “at a farm rent of ten pounds payable on September 30 in each year,”1 that the city transformed into an important commercial port and trading center. Bombay attracted people from various parts of the Indian subcontinent, who migrated to establish businesses in this bustling city. Moreover, growing trade in cotton, opium and spices brought a lot of wealth into Bombay.

Over time, the constant influx of working class residents and the ever-growing need for housing led to land reclamation, thanks to which the trading center evolved from seven islands into one island city. In the early twentieth century, Bombay saw a transformation of its social, cultural and political framework, a transformation mirrored in its physical form through Art Deco.

Mumbai’s Art Deco

Art Deco entered India from Bombay, thanks to Indian princely statesmen, merchants and entrepreneurs, as an expression of their love for contemporary ways of living. It signaled the arrival in India of an appreciation for modern aesthetics. Ornamentation, a significant part of Indian architecture, remained an integral part of the language of Art Deco, but took the form of minimal and geometrically driven design. The new emerging architectural spaces in Bombay such as cinemas, social clubs, schools, hospitals and apartments adopted this modern style. In addition, newly trained architects – especially those from India – graduating from local or international schools embraced this style and incorporated it in their own designs. India’s first architectural exhibition, the Ideal Home Exhibition organized by the Indian Institute of Architects at Town Hall in November 1937, enlightened the public about new styles, furniture, and such building materials as reinforced cement concrete (RCC) and ferrocement, making the architectural movement more visible within the city as well as the country.

As the style gained popularity, it evolved into a more pronounced expression of Indian aspirations as opposed to the initial European influences. These indigenous expressions of Art Deco are widespread in buildings around the northern suburbs of the city such as Dadar and Matunga, and are commonly referred to as Bombay Deco or Indo Deco. At the same time, the style had a more direct influence on Bombayites’ lifestyles through industrial design, graphic design, fashion and mass media. Although the design sensibilities of Art Deco in the West thrived on industrial means of production, India continued to rely on manual labor for construction. This gave Indian buildings a hand-made quality different from their western counterparts, while creating a highly skilled workforce that eased the architectural transition in the late 1940s.

Deco Precinct: Backbay Reclamation

After World War I, the pressing need for more housing led to the reclamation of various areas around the city. The Backbay Reclamation Scheme, undertaken in November 1920 and completed in 1929, identified 439.6 acres of reclaimed land available for building. Blocks I and II at the northern end of the Backbay Reclamation Scheme compose what we know today as the Art Deco Precinct that stretches from the western edge of Oval Maidan (East) to Marine Drive (West). The Maidan, a public park, was developed in the early 1930s, and Marine Drive soon after.

To ensure proper architectural and urban form, the development was controlled by special laws that governed details such as building location, use, footprint, height, number of floors, structural design, finish and color. To maintain general uniformity and harmony, specific rules regulated the overall design and types of permanent architectural features. These rules created a unique massing, delineation of the precinct, and skyline. In the case of Marine Drive, the plots facing the sea were assigned primarily to residential use.

Residential buildings were also constructed on the plots that ran along the Queen’s Road (now Maharshi Karve Road) facing the Oval Maidan, creating a unified urban fabric even though each building showcases its individuality through design. Most of these buildings, especially Shiv Shanti Bhuvan and Rajjab Mahal, have highly decorative surfaces that evoke a sense of flamboyance in the way they use color, banding details, relief patterns, and motifs are used.

Architectural lettering was also incorporated into the building design as part of a larger ornamental scheme. Stylized fonts along with varied materials such as wood, metal, stone, and plaster were used to create building name signs. There was also a sudden shift in building names within the precinct, reflecting the changing political climate of the country at that time. Colonial names like Empress Court, reflecting a European aspiration, gave way to Bharatiya Bhavan which translates to “Indian house.”

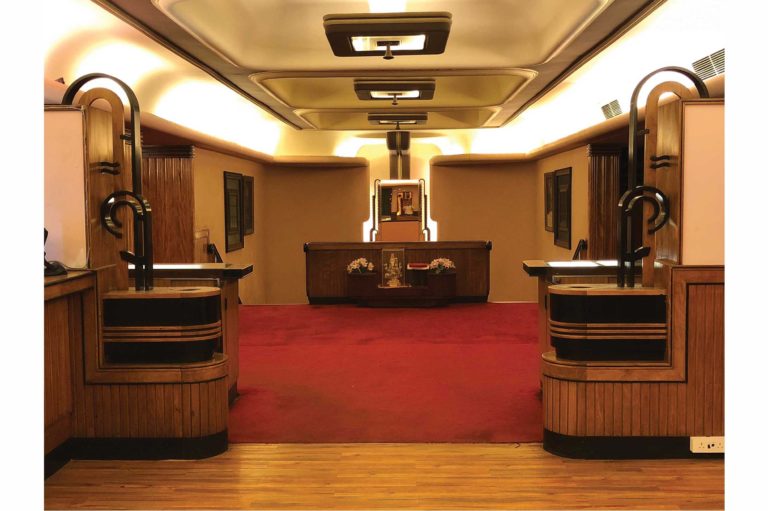

Deco Cinemas

Beginning in the 1930s, the widespread popularity of cinema in Bombay led to the construction of many theaters. These new cinemas, all built in Art Deco style, had a great visual presence in the city’s urban landscape.

The Regal, built in 1933 by architect Charles Steven – son of F. W. Stevens, designer of some of Bombay’s most significant Victorian public buildings – was the city’s first Art Deco cinema. A multi-use structure, it housed a fully air conditioned theater with shops on the ground floor and underground parking. Its modern design included towers and rectangular slabs stepping back on the façade to sensitively complement features such as the gables, turrets and domes of the nearby Wellington fountain.

Another iconic theater, and the only non-residential building along the Oval that sits in a commanding position within the Backbay Reclamation, is the Eros Cinema. This V-shaped structure is a mixed-use building partially clad with red Agra sandstone that contrasts with the light cream painted finish on the overall facade. A prominent ziggurat-like tower, and the further use of the color red to accentuate ornamental features on the façade, add the illusion of height, so it appears to be a lot taller that its actual size. The Eros serves as a visual marker in the Churchgate area within the Backbay Reclamation Scheme.

Residential Buildings

Although cinemas in Mumbai popularized Art Deco architecture, it was the large set of residential buildings within the Oval and Marine Drive precinct that transformed Mumbai’s image from a Gothic colonial outpost to a modern and cosmopolitan world city. The two open spaces around the area, the Oval Maidan and Marine Drive, formed the fulcrum around which the Art Deco district developed and continued to flourish in subsequent decades.

The residential Art Deco buildings along the western edge of the Oval facing the imposing Victorian Gothic buildings, with the open Maidan in the center, form a captivating urban composition. These buildings – despite their varying styles, scales, uses and materials – engage city dwellers in a fascinating dialogue between the two styles, while standing tall as an individual cluster of buildings from the heydays of the two centuries.

Mumbai’s Art Deco buildings bear witness to a very important period in the history of the city and India. Through their physical form, they captured the aspirations of a colonized India ready to become independent and modern. These living spaces were designed with the intention of evoking a sense of ownership while transcending time. Even today, most citizens of the city, across generations, identify and continue to interact with them every day. Although their numbers across the city make them one of the largest collections of Art Deco buildings in the world, it is the fact they are still in constant use by city dwellers that keeps them relevant and significant. Hence, this precinct forms an important part of Mumbai’s modern living heritage.

Atul Kumar is a Founder Trustee and Nityaa Lakshmi Iyer is the Head, Documentation & Research, of the Art Deco Mumbai Trust. For Mumbai’s World Heritage Site inscription: ArtDecoMumbai.com/#UNESCO. For a tour of the Art Deco precinct in Mumbai: ArtDecoMumbai.com/Guided-Tours.

All photographs are by Art Deco Mumbai Trust except where attributed otherwise.